Edward Grew

Google Scholar Profile | Geodynamics

My current research focuses on the minerals of boron and beryllium and the role of these two elements in the changes rocks undergo at high temperatures and pressures in the earth’s crust, especially in the granulite facies. Due the abundance of phosphate minerals associated with borosilicate minerals in my field area, I studied these as well and discovered three new species in the Larsemann Hills, Prydz Bay , Antarctica (Figure 1). One of these, chopinite, I later discovered in a meteorite. Following the tradition of the late Charles Guidotti, formerly a professor in our department, I describe my research as “petrologic mineralogy” because I study minerals in their petrologic context. Work with light elements requires special techniques so an integral component of my research is analysis for Li, Be and B in minerals with the ion microprobe (secondary ion mass spectrometry). I do these analyses in collaboration with Charles Shearer at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. In August, 2009 I was awarded a research grant from the National Science Foundation to analyze borosilicate minerals for boron isotopes, and for this ion microprobe work I have collaborated with Simon Harley at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

My professional activities in the mineralogical community have included my service as Associate Editor of Canadian Mineralogist (2003-2005), American Mineralogist (2005-2010) and Mineralogical Magazine (2006-present). In 2011 I became chair of the subcommittee to review the nomenclature for the group of garnet minerals. This subcommittee was established by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association. I previously chaired a similar subcommittee for the nomenclature of the sapphirine group. In 2012 I am one of the candidates running for the office of Treasurer of the Mineralogical Society of America. My activities also include public outreach events such as “Sunday with a Scientist: Rocks and Minerals” at the University of Nebraska State Museum in December 2011. Here are more details on recent and current projects:

Phosphate minerals in granulite-facies metamorphic rocks and anatectic pods

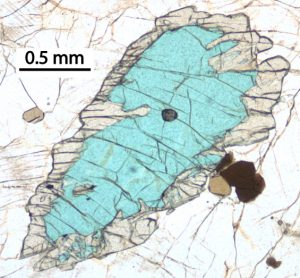

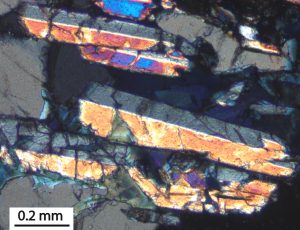

My current National Science Foundation supported project is a study of boron-rich paragneisses in the Larsemann Hills based on samples collected on the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition in 2003-2004 with Chris Carson (Geosciences Australia). The ferromagnesian borosilicates grandidierite and prismatine are major rock-forming minerals in these paragneisses (Figure 2).

The Larsemann Hills is the type locality for boralsilite (Figure 3), a mineral related to sillimanite that I discovered in 1998.

My former student Eva Wadoski completed a Master’s thesis on borosilicates in the pegmatites, with a focus on tourmaline, presented posters at several international meetings (Figure 4), and she published a paper in the Canadian Mineralogist (Wadoski et al. 2011).

My current student, JohnRyan MacGregor, has analyzed tourmaline, prismatine and grandidierite for boron isotopes at the University of Edinburgh (Figure 5) as part of his Master’s thesis research. His objectives are to determine isotopic fractionation among these three borosilicates and to constrain possible protoliths of the boron-rich metasedimentary host rocks.

Borosilicate minerals in granulite-facies rocks

The Larsemann Hills contain a remarkable variety of phosphate minerals for a metamorphic complex (9 species), including 3 of the 4 known polytypes of iron magnesium fluorphosphate wagnerite and 3 new species: stornesite-(Y), tassieite and chopinite. The last is a high-pressure polymorph of the meteoritic mineral farringtonite, Mg3(PO4)2, so my discovery of chopinite in Graves Nunatak 95209 (Figure 6), a primitive achondrite , raises questions about the evolution of the asteroid from which this meteorite originated.

Evolution of the minerals of beryllium and boron

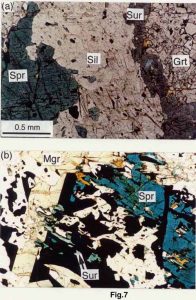

Robert Hazen invited me to collaborate on a series of papers on the mineral evolution of specific elements as follow up of his 2008 paper “Mineral Evolution” published in American Mineralogist, vol. 93, pp.1693-1720. I started with the 106 minerals of beryllium, the oldest of which formed in the Mesoarchean. I have studied three Be minerals, khmaralite, magnesiotaaffeite-6N’3S (formerly musgravite) and surinamite from the earliest Paleoproterozoic (2485 Ma) granulite-facies anatectic veins in the Napier Complex, Antarctica (Figure 7). Of particular interest is the role of borates in the “RNA World” thought to have been an important link between purely prebiotic (>3700 Ma) chemistry and modern DNA/protein biochemistry. However, it remains an open question whether borate minerals were around so early in Earth history (Grew et al. 2011).

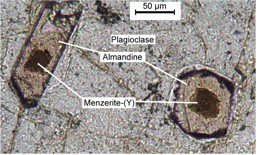

Menzerite-(Y), new species of garnet, and the garnet nomenclature

Jeff Marsh, who was awarded a Ph.D. in 2010, discovered an yttrium rich mineral in a pyroxene granulite on Bonnet Island (Figure 8 ) in the interior Parry Sound domain, Central Gneiss Belt, Grenville Orogenic Province, Canada, his thesis area. Crystallographic studies show the mineral is a garnet (Figure 9), and the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association has approved our proposal for the new mineral, menzerite-(Y), which was described in the Canadian Mineralogist (Grew et al. 2010). I am currently chairing the Garnet Subcommittee, which is preparing a recommended nomenclature for the Commission to vote on.