Champlain and the Settlement of Acadia 1604-1607

Champlain and the Settlement of Acadia 1604-1607

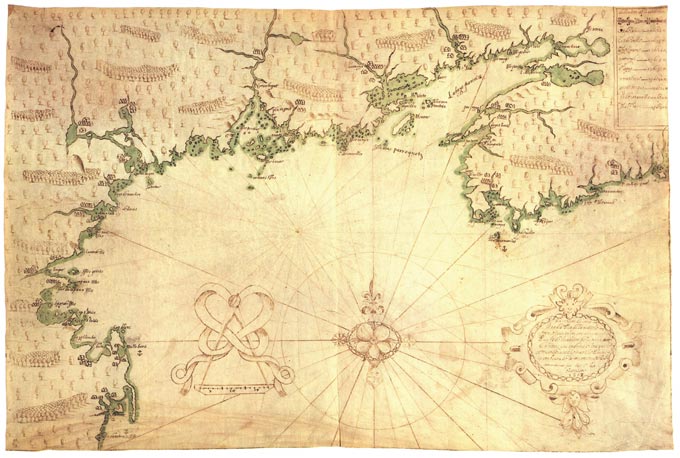

Champlain’s map of the Gulf of Maine and Bay of Fundy

Champlain’s Descr(i)psion des costes-(1607) is the first detailed map of the gulf of Maine. Drafted at Port Royal, the map shows capes, bays, islands, shoals, and rivers along the coast; heights of land useful for navigation; and principal native settlements. Indian guides helped Champlain explore parts of the coast, and also provided information about the interior. Of the French names given to geographical features along the Maine coast, only Mount Desert and Isle au Haut have survived to the present. [larger version of map]

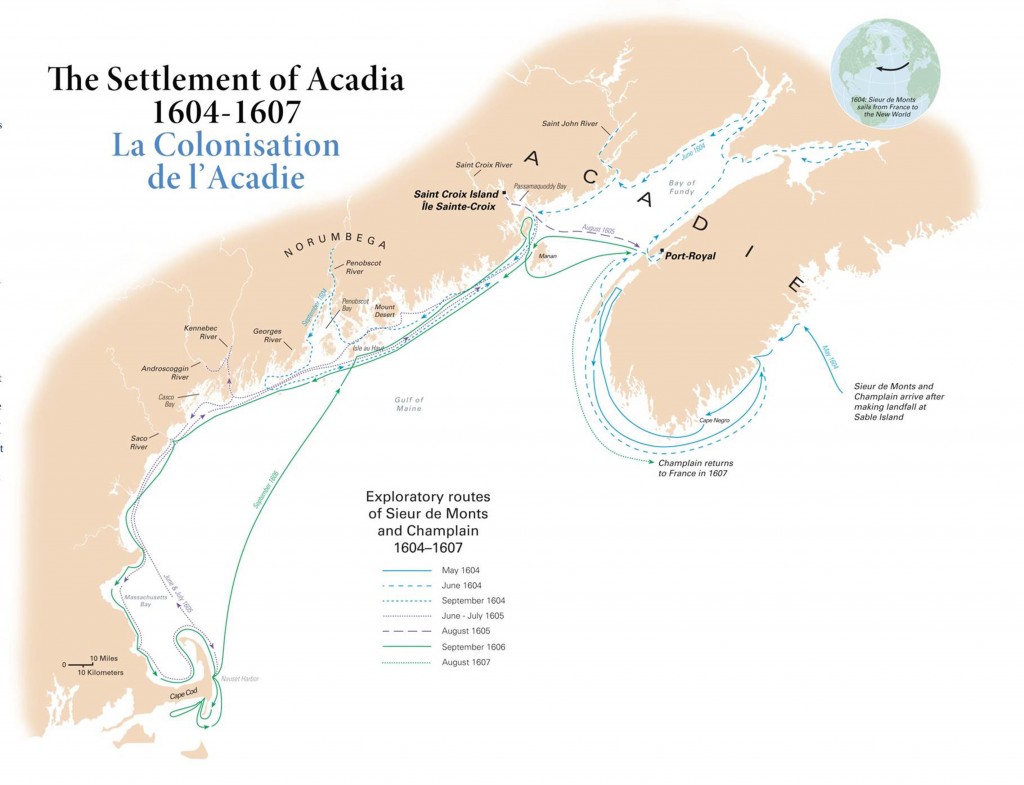

This project commemorates the 400th anniversaries of the French settlements on Saint Croix Island (Maine) in 1604 and at Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) in 1605. Although both settlements were short-lived, they mark the beginnings of a French presence in the area that the French called Acadie (Acadia) and that today comprises eastern Maine and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island.

In the early 1600s, the French and the English, taking advantage of weakening Spanish power in the western Atlantic, began to assert their claims to the eastern seaboard of North America. In the northeast, these claims overlapped; the Gulf of Maine was soon divided between English interests in and around Massachusetts Bay and French concerns around the Bay of Fundy.

In 1604, a French expedition led by merchant venturer Pierre Du Gua, Sieur de Monts, and including geographer and cartographer Samuel de Champlain, arrived off the coast of what is today southwestern Nova Scotia. After exploration of the Bay of Fundy, a settlement was established on Saint Croix Island. During the summer and early fall of 1604, Champlain ventured along the mid-Maine coast as far as Georges River. He named the islands of Mount Desert and Isle au Haut, both significant navigational landmarks, and explored up the Penobscot River in search of the mythical city of Norumbega.

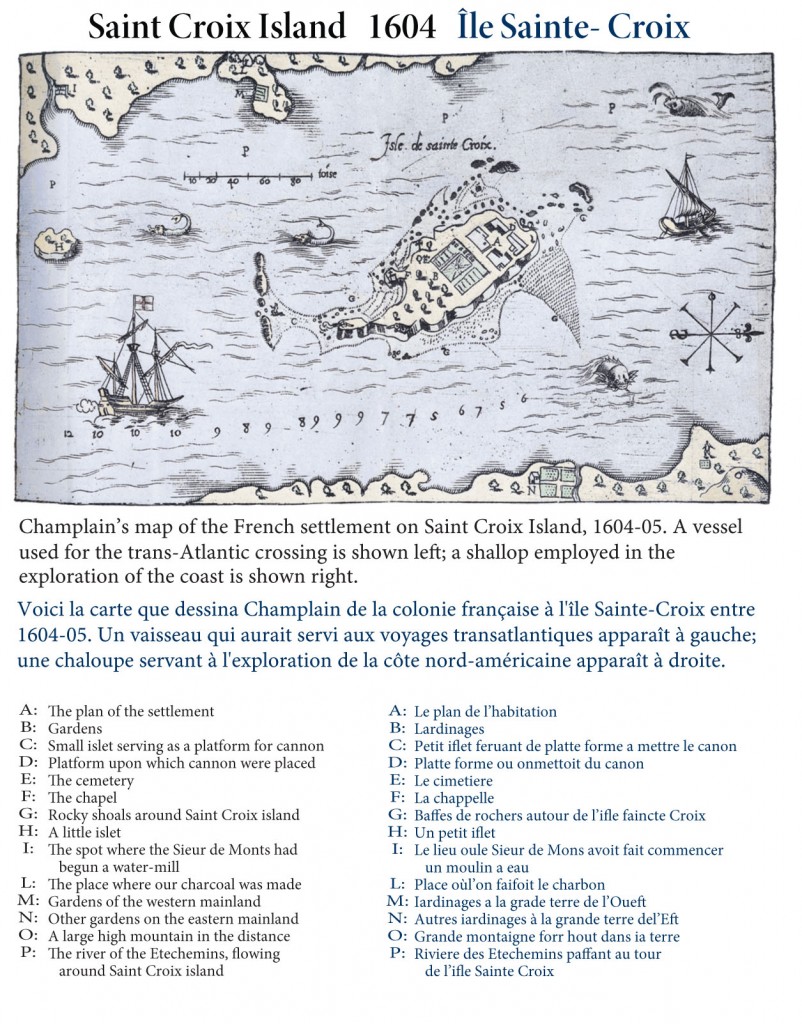

Saint Croix Island 1604

The French first settled on Saint Croix Island in the middle of the Saint Croix River. In his journal, Samuel de Champlain observed: “It was difficult to know this country without having wintered there; for on arriving in summer everything is very pleasant on account of the woods, the beautiful landscapes, and the fine fishing for the many kinds of fish we found there. there are six months of winter in that country.”

The French selected Saint Croix Island because of its good location, safe anchorage, and apparently defensible site. During the summer, houses, stores, and a chapel were hastily erected, while gardens were planted on the island and on a neighboring river bank. However, a bitter winter led to the abandonment of the settlement. The freezing of the Saint Croix River left the site vulnerable to attack, while a shortage of fresh food led to an outbreak of scurvy and the death of thirty-five men, nearly half of De Monts’ company.

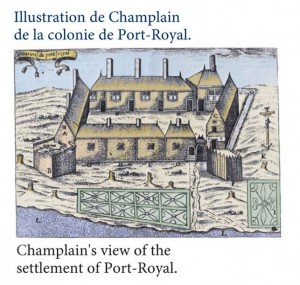

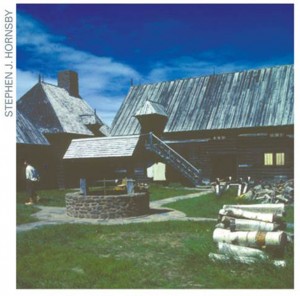

The following summer, De Monts and Champlain took a small expedition southward along the coasts of present-day Maine and Massachusetts as far as Cape Cod. The party entered the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers, sailed across Cape Cod Bay, and reached Nauset Harbor on the Cape. On their return, De Monts removed the settlement from St. Croix across the Bay of Fundy to a new location at Port-Royal overlooking Annapolis Basin. The habitation built at Port-Royal was a defensive structure that accommodated the colonists, their supplies, and workshops; it was the forerunner of similar trading posts built by the French elsewhere on the continent during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. During the winter of 1605/6, a further twelve men died of scurvy.

In the summer of 1606, Champlain worked on his map of the region, as well as explored around the southern tip of Cape Cod. The winter of 1606/7 was much easier, but just as the small colony seemed to be establishing itself, the French crown revoked De Monts’ charter. In the summer of 1607, all the colonists, except a caretaker, left for France. During their four years of colonization, the French had acquired considerable geographical knowledge of the region, traded with native peoples, and shown that arable cultivation was viable.

In the early twentieth century, French exploration and settlement of Acadia was commemorated in Maine and Nova Scotia. In Maine, the federally-protected lands on Mount Desert Island were first named the Sieur De Monts National Monument, then Lafayette National Park (after the Revolutionary War hero), and finally Acadia National Park. A mountain in the park was named after Champlain and a spring after Sieur De Monts. In Nova Scotia, the habitation at Port-Royal was reconstructed in the 1930s and is now a National Historic Site. The names of the national park and the reconstructed habitation are significant monuments of the Colonial Revival movement.