Great Pond, “John Roberts”

Song: “John Roberts”

Singer: Clarence Berry

Town: Events described took place on the Union River near Great Pond, ME; recorded in Jacksonville, ME

ID: NA0420 CD 10 Track 2

Collector: Muriel Watts

Date: December 5, 1963

Roud: 2222

Laws: C3

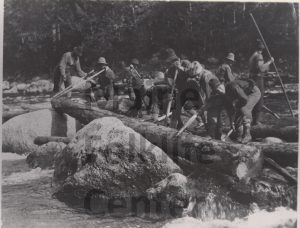

“John Roberts” is one of many woods songs that tells the sad tale of a river driver who died on the job. There were more popular songs, such as “Peter Emberly” and “The Jam on Gerry’s Rock” which were both better known in the region and across North America, but they were not native to Maine. (As a side note, no one really knows where Gerry’s Rock is, so in truth it could be a Maine song.) Many of these sad ballads are claimed to be true by the men who sing them, but upon further review are difficult to authenticate. Moreover, many of these songs (such as “Gerry’s Rock”) are claimed as true by people all over the region and continent. In other cases, such as “Peter Emberly,” we can authenticate the story with evidence such as gravestones that still exist or newspaper articles. “John Roberts” is an interesting case where we know it is a true story, but it is claimed by woodsmen all over the state.

The song was known to many as “The West Branch Song” and everyone simply assumed it referred to whatever river they worked on. Bill Cramp and other woodsmen thought it was the West Branch of the Penobscot and Clarence Berry figured this meant the Machias River. But the song referred to neither, instead it was about the death of a man on the Union River, a relatively small river that runs through Ellsworth into the ocean. John Roberts drowned near Great Pond on April 22, 1859, a date still visible on his gravestone in Aurora, ME. Like most other doomed river drivers who became the subject of song, Roberts perished while breaking a jam. In his case, it was a jam at a roll (or rolling) dam near Great Pond. Roll dams were a dam without gates or sluices so the water and logs rolled over the top. They were built at the head of falls or rough water on smaller rivers and streams. Their purpose was not to hold water, but to increase depth so logs would keep flowing or rolling along. In a different version of the song, Roberts supposedly rose to the surface three times before he died, and in all versions his body is found at three o’clock on the third day. While the song is “true,” it does not mean all of these details are completely accurate. Instead, they may be symbolic and relate to the admonition to be good Christians in the final stanza.

A few other notes on this song may be interesting. First, Clarence Berry’s version shows the perils of improvising. He sang it with rhythmic inconsistencies in several lines, but he always sang it the same way. It was therefore not a mistake; rather, he must have learned it or changed the song that way. Second, Eckstorm and Smyth noted that Charley Roberts (John’s brother) was killed at the same place near Great Pond a year later. Supposedly, while eating his lunch on shore a dead tree fell on him. However, this was based on a story told by Eckstorm’s father and no one has confirmed the story. Finally, the man mentioned in stanza 8 was the real person who found Roberts’ body. Roswell Silsby – his name is pronounced incorrectly here – was later buried along with John in the Roberts family cemetery plot.

Lyrics:

1.

Come all ye fellow men, from far and near,

A melancholy tale to hear;

One of our fellow mortals, he

Has gone to his long eternity.

2.

John Roberts as we understand,

It was the name of this young man;

Whose fate we hope will a warning prove

To all who do these lines pursue.

3.

He hired out with Mr. Brown,

To help him drive his lumber down;

On the West Branch, where he did go,

Which quickly proved his overthrow.

4.

‘Twas of a lowery sky,

This young man left his home to die;

When from his home he did depart,

A gleam of hope twined round his heart.

5.

He ventured out to break a jam,

Which had begun on the rolling dam;

But when he started for the shore,

He sank, alas, to rise no more.

6.

We think he got his fatal blow,

While struggling in the undertow;

By some huge rock beneath the waves,

Where soon he found him a watery grave.

7.

We searched the stream from shore to shore,

His lifeless body to secure;

Trusting in God to guide the way,

Unto his tenement of clay.

8.

‘Twas on the third day at three o’clock,

When Mr. Filsber [sic] took his boat,

And with a grapple in his hand,

He raised him from his bed of sand.

9.

A message then was sent away,

These mournful tidings to convey,

Unto his tender parents dear,

To tell them that they’d see their son no more.

10.

And in due time a bier was made,

And on it was his body laid;

Born to the grave where he shall lie,

Til Gabriel’s triumphs shall render the sky.

11.

We fellow men, we too must die,

And go to our long eternity;

So let us live while here below,

Love God and all his paths pursue;

And let us live in Christian love,

And go with him to reign above.

Sources: Eckstorm, Fannie Hardy and Mary Winslow Smyth. Minstrelsy of Maine: Folk-Songs and Ballads of the Woods and the Coast. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1927, 45-48; Ives, Edward D., ed. “Folksongs from Maine,” Northeast Folklore, VII (1965), 36-40; Laws, G. Malcolm, Jr. Native American Balladry. Revised Edition. American Folklore Society, Bibliographical and Special Series, 1. Philadelphia: American Folklore Society, 1964, 148-48 (C3). For another version, see Gray, Ronald Palmer. Songs and Ballads of the Maine Lumberjacks with Other Songs from Maine. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924, 22-23. For further reading on the Union River, see Edward D. Larry Gorman: The Man Who Made the Songs. Fredericton, NB: Goose Lane Editions, 1993, 79-103.