UMaine leads international team to study, conserve woodcock

The American woodcock, a plump harbinger of spring, is a well known shorebird found across eastern North America. The species is a popular game bird and has earned the admiration of hunters, birders and others through their spring display, whistling wings and unique quirks. Each year they make an impressive migration from their overwintering locations in the southeastern US to breeding locations across the Northeastern and Midwestern United States and southeastern Canada.

In 2017, this migration became an increasing topic of conversation amongst researchers, resource managers and admirers of the American woodcock. In response, the Eastern Woodcock Migration Research Cooperative was co-founded by University of Maine avian experts Erik Blomberg and Amber Roth, both faculty at UMaine’s Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Conservation Biology which Blomberg chairs. Roth also holds an appointment in UMaine’s School of Forest Resources.

The international collaboration brings together a plethora of partners invested in the management of American woodcock. The UMaine-led team has formally collaborated with 15 different state natural resource agencies, federal agencies in the United States and Canada, a number of conservation nonprofits and two other universities.

Data from the project, which is supported by UMaine’s Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station through the College of Earth, Life, and Health Sciences, has also created opportunities for students. Dissertations of three UMaine Ph.D. students, one master’s student, a postdoctoral researcher and two undergraduate Honors theses all drew from the Cooperative’s extensive collection of data on the diminutive birds.

“It is really exciting to join something that feels like it’s got a real world impact. We have all these agencies, nonprofits and other affiliates that are working with us trying to develop management tools,” expressed Kylie Brunette, a UMaine master’s student in the wildlife ecology program working on the project.

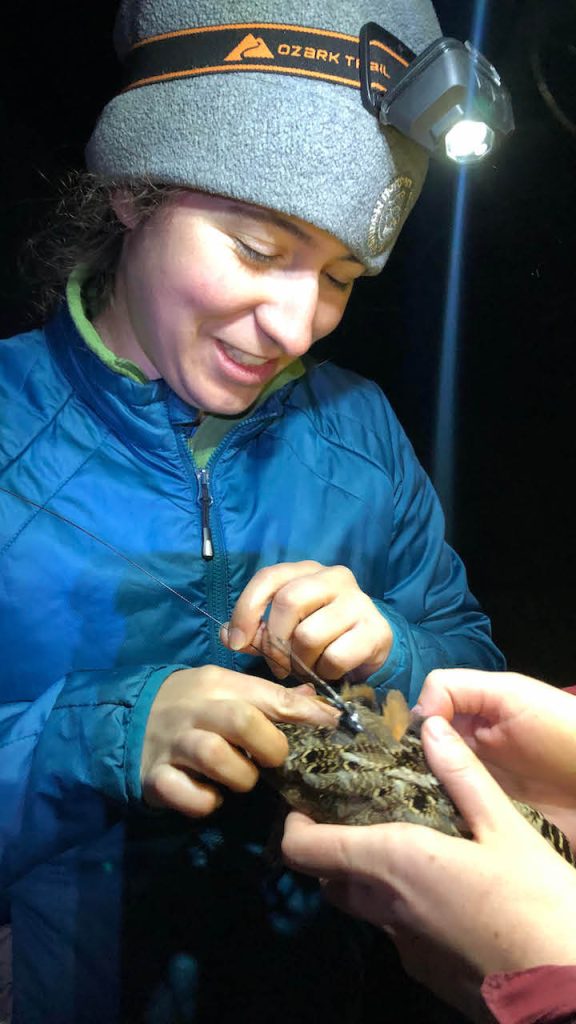

Researchers use GPS trackers affixed to the birds to study their movement throughout the year. Roth explained, “Because the tags are GPS accurate, we get a high level of resolution that a lot of other tag technologies don’t give us. This allows us to answer a lot of questions that we can’t answer with other technologies.” Specifically, researchers are able to track the birds latitude and longitude, and more recently, altitude, all synced with a timestamp. “We can reconstruct what their likely flight trajectories were and relate that to what kind of habitat they were in on the ground. We can look at how different individuals migrate at different times and the weather conditions that coincided with their movements,” explained Blomberg.

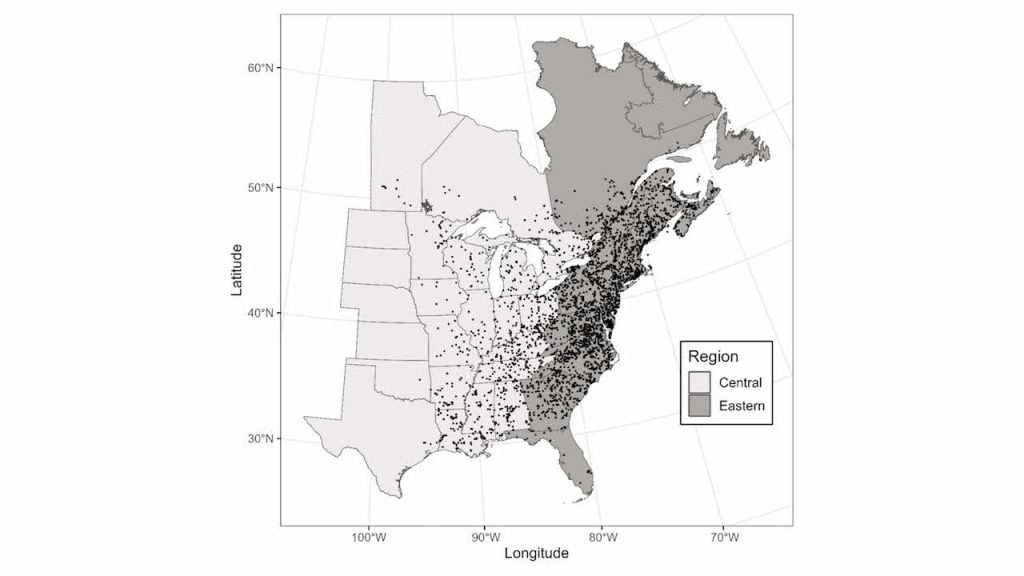

The collaborative nature of the work has generated a massive dataset with nearly 700 individual woodcock tracked by GPS. Through their migrations, these birds have flown to nearly the full extent of the species’ range in North America, through 32 states and seven Canadian provinces. This work does not come without its challenges, however. A woodcock can only carry so much weight which limits the size and battery of the trackers. Researchers like Rachel Darling, a UMaine Ph.D. student in wildlife ecology on the project, have to perform a balancing act as they try to collect data without bleeding the battery dry. Researchers could ping the tracker each day but that can only be maintained for three months, at best. This necessitates compromise as the team collects data less often in order to follow a bird’s path for an entire year.

One of the major hurdles these birds face during their migration is physical infrastructure. “They tend to be a species that often is found to collide with high-rise buildings and low-rise buildings for that matter, in particular in a handful of key areas like New York City, Minneapolis, Chicago, and Toronto,” Blomberg remarked. While existing high-rise buildings are not going to move out of the way, new construction of infrastructure could be adapted to accommodate migration paths. The researchers help woodcock managers by creating tools to inform management decisions, like maps of major woodcock populations centers. Brunette works with the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to do just this. Using the GPS data, Brunette maps where woodcock are in a select number of ecoregions defined by West Virginia’s DNR, which helps the agency hone in on where management efforts will be most effective. What is effective in West Virginia, though, may not be effective in Georgia or Ontario, so it is important to have agencies from across the eastern region engaged in creating tools that best meet the needs of each area.

The American woodcock has proven to be resilient. The project has already looked into the birds’ migration strategies, the combinations of behaviors that collectively define how individual woodcock migrate. A former postdoctoral fellow with the project, Sara Clements, evaluated migration strategies and observed that individuals did not fall into discrete categories of behaviors, but rather strategies existed as a continuum with considerable variability among individual woodcock, even from the same location. This finding, which was published in the journal Ornithology, illustrates the potential for behavioral flexibility within woodcock populations that may make them more resilient to future change.

Alexander Fish, who completed his Ph.D. in 2021, used the cooperative data to evaluate the timing of woodcock migration in comparison with the annual hunting seasons for the species. This research, published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, provided wildlife managers with tools to determine the timing of hunting seasons for the species. The seasons are fixed to a certain number of dates by a federal regulatory process, and must account for hunter opportunity while ensuring their harvest is sustainable. Understanding the timing of the birds’ migration is critical to this process.

The Cooperative also collects genomic data to learn more about the American woodcocks’ life cycle. Darling, for instance, is looking at genomic data from GPS-tracked woodcock in the central and eastern management zones to understand if woodcock migrations between the two also affect population structure.

GPS tracking data suggests that up to thirty percent of woodcock cross between these two zones during migration. However, there also appears to be relatively high breeding site fidelity, as Darling stated, “Return data indicates most birds kind of stick within the same area within, maybe like 50 to 100 kilometers of where they hatch. The birds we’ve tracked for more than a year pretty much all go back to the exact same spot to breed.”

Blomberg identifies as a woodcock optimist. While the species has faced an amount of adversity, the birds still make their voyage hundreds and hundreds of miles across the continent each year. Their admirers can find them in Maine come springtime where their displays can be observed at dusk. Learn more about the project online.

Written by: Daniel Timmermann

Contact: Erin Miller, erin.miller@maine.edu