Challenges, Responsibility, and Opportunity:

The Case for the Strategic Re-envisioning of

the University of Maine

Joan Ferrini-Mundy, President

University of Maine and University of Maine at Machias

October 11, 2024

Introduction / Our Current Situation at UMaine / Strategic Re-Envisioning Initiative / Higher Education’s Responsibility to Shape the Future / Our Opportunity to Enable Learners to Lead and Innovate for Tomorrow / Conclusion / Acknowledgments / References

Introduction

Higher education is a dynamic enterprise by its very nature. On an annual basis, students graduate, new students begin, faculty and staff join institutions and leave them, and leadership terms expire and are renewed. The curriculum is revised to remain relevant, programs are introduced and sunsetted, and pedagogies shift to foster learner success based on new research and the affordances of new technologies. The research endeavors of an institution evolve, continually shifting the frontiers of science, technology and other creative pursuits.

At the same time, higher education in the U.S. remains one of the most intransigent sectors of collective change, considering that it is comprised of more than 5,000 institutions. Foundational disciplines, themes and subject matters within the curriculum are not left behind lightly; basic research is always essential. Complexities of shared governance, collective bargaining, tenure systems and risk-averse individuals — all critical to the health and sustenance of the higher education enterprise — can also complicate the pursuit of change agendas.

Yet higher education, perhaps the most influential sector, remains. Michael M. Crow, the innovative president of Arizona State University, reflected:

“Higher education represents our best hope for the advancement of individuals, society, and our planet. We need to work collaboratively to innovate, adapt, and leverage technology to create new and effective learning pathways for all” (Crow, 2022).

I agree, and the University of Maine has an essential role in this redefinition of higher education.

Our Current Situation at the University of Maine

We have major challenges to address. The first, and it is overarching, is that our expenses exceed our revenues. This is not a new situation for the university. For many reasons, this situation cannot be well managed without taking a step back to look at opportunities for change:

Strategic Re-Envisioning Initiative

We at UMaine have faced and persevered through financial challenges in the past. However, this time is different. Stability is no longer sufficient. The higher education landscape, the workforce and the student-college experience are all in a state of flux. Our Strategic Re-Envisioning initiative (SRE) acknowledges that transformational change is not just a necessity but our calling. As Maine’s public land-grant, R1, D1, flagship university, we find ourselves uniquely positioned to not only serve this state but to advance it, and that all rests on remaining inclusive, accessible and relevant for another 160 years. Solving these challenges is both our responsibility and an opportunity.

Higher Education’s Responsibility to Shape the Future

Many others highlight the criticality of higher education in shaping the future of society. Teague (2015) notes higher education’s role in and relevance to our nation’s “ability to compete in the global marketplace and is critical to our economic strength, social well-being, and position as a world leader.” The University of Maine’s contribution to social mobility alone is worth examining more closely. Over the past five years, our enrollment has averaged 25% first-generation college students and 27% Pell-eligible students. We must meet all students where they are (something that has become more complex since the pandemic) and ensure that a degree from our university enables them more choices, more pathways to success, and more personal fulfillment than they might have had otherwise.

According to Gunja and Gast (2024), “Success in [fostering student success] depends primarily on two questions: Are we opening our doors to a wide range of students? And are those students leaving college with an education that puts them closer to the future they have dreamed of and worked for?” We must make the case for new indicators of a university’s impact on students’ mobility. It is part of the public university’s responsibility. Just as we are proud of our Carnegie R1 classification, we should strive to develop Carnegie’s new social mobility classification.

We face a point of inflection, where in mathematics (and the evolution of a university) the concavity shifts and the rate of change quickens. To be relevant, to serve our many responsibilities, and to be a sustainable university, I propose a serious and widespread commitment to this acceleration.

Our Opportunity to Enable Learners to Lead and Innovate for Tomorrow

Every higher education institution today faces challenges, whether it be declining enrollments and skyrocketing expenses, the need to confront the realities of climate change and all of its impacts, widespread social unrest and injustice, wars and violence, or the erosion of civil discourse. Stasis and business as usual, and the slow rate of change that characterizes universities, may not be sufficient to address those challenges. And it is definitely not adequate for imagining the role of universities, whose research, education, and engagement are foundational to preparing our future graduates to be leaders and innovators of tomorrow’s complex world.

The University of Maine is globally connected. This year it enrolls students from 83 countries outside the United States, and its alumni from those countries total in the thousands. We must ensure that a UMaine education prepares future teachers, nurses, musicians, finance leaders, engineers, policymakers and more, not only for Maine but for the world.

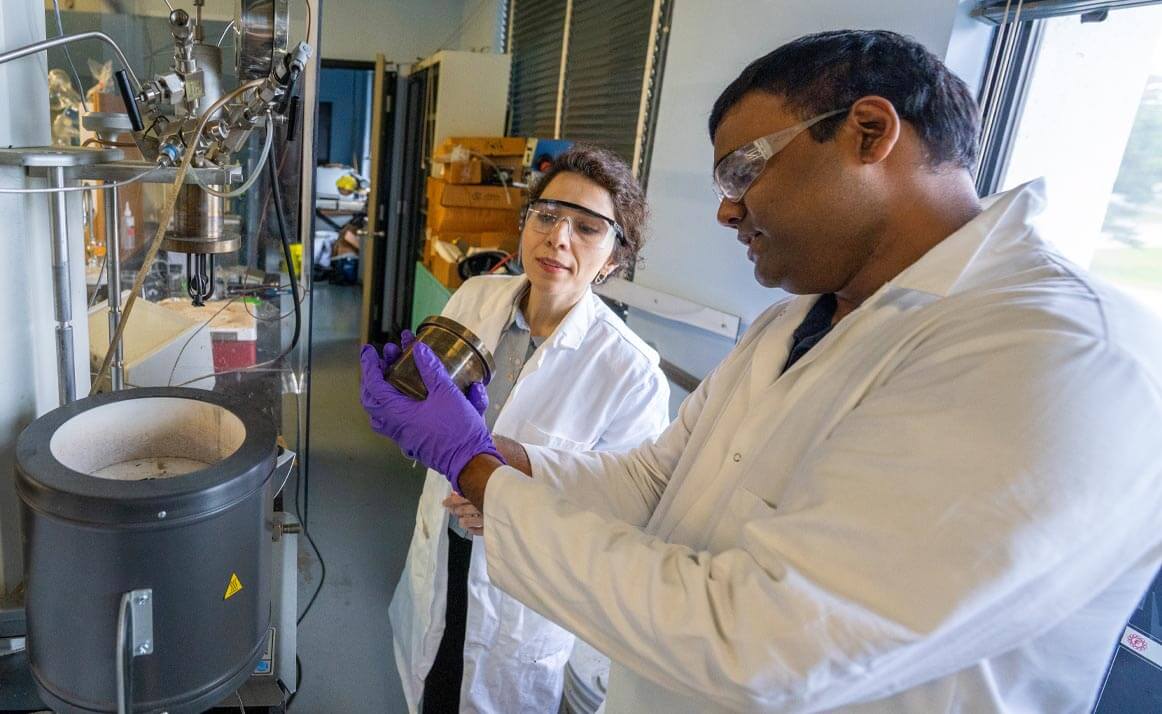

Those of us from the University of Maine — home for more than 50 years to the world-renowned Climate Change Institute — know the realities of what the planet faces with a changing climate. Our scientists have helped to build current understandings of everything from what causes rapid glacial melt, to how climate changes worldwide directly affect sea-rise levels and the chemical composition of the Gulf of Maine, to how best to measure and predict climate-related weather variation with AI-based tools. A steady linear increase in the cumulative warming effects of greenhouse gases challenges the planet. Global increases in average annual temperatures are profoundly affecting human health, food and water supplies, and economies worldwide (World Health Organization, 2023).

This knowledge is not only contributing to the core of scientific foundations, it is informing policy, as reflected in Gov. Janet Mills’s Climate Action Plan: Maine Won’t Wait (Maine Climate Council, 2020). And while climate impact is increasing by most measures, around the world climate policy actions are lagging: after increasing worldwide on average by 10% from 2000 to 2021, they have leveled off to roughly 1% annual increases since (OECD, 2022).

As the complexity of the world’s challenges increases, the number of students seeking 4-year undergraduate degrees worldwide is decreasing. A study by the Brookings Institution found that only 23% of high school students in the bottom quintile of poverty enrolled in a 4-year degree program within 18 months after expected graduation from high school (Reber and Smith, 2023). Furthermore, we have seen declining enrollment at 4-year institutions over the past five years. According to the National Student Clearinghouse, although the number of students pursuing bachelor’s degrees at public four institutions was slightly higher in fall 2023, it was still 5% lower than in 2018 (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2023).

Here in Maine, we have seen a decrease in the number of high school graduates attending 4-year institutions: The proportion of high school graduates attending a four-year college had hovered around 46% prior to the pandemic but dipped to 39% in fall 2022, the most recent year of data available (National Student Clearinghouse, 2023). We are at a moment when the need for talent, ingenuity, aspirations for peace and humanity, and solutions to endemic problems are priorities. How does our public university do its part?

Public land-grant universities that were initiated in the first Morrill Act were mandated to be practical, problem-focused, regionally oriented, and perhaps most significantly, to democratize education. The Morrill Act directed them to “teach agriculture, military tactics, and the mechanic arts as well as classical studies to members of the working classes could obtain a liberal, practical education” (APLU, 2012). What does the land-grant university of today and tomorrow look like? We should serve all students no matter their socioeconomic status, and we should continuously redefine what a practical and liberal arts education means. It seems clear that a reasonable starting point is to consider how to address the global challenges that affect our state. How do we ensure our students have the knowledge and skills not only to participate in that effort but also to lead civil discourse?

Depending on the year and the poll, Maine is the nation’s first- or second-most rural state (Maine Department of Health and Human Services, 2024; World Population Review, 2024). With this rurality come special challenges for higher education:

These challenges exist in the context of troubling demographics. Since 2012, the number of deaths in Maine has exceeded the number of births. We are an aging state: Approximately 22.5% of Maine’s population is age 65 or older, making us the “oldest” state in the U. S. – and that percentage is expected to exceed 30% over the next 15 years (Maine Department of Administrative and Financial Services, n.d.).

Will our research on aging, our preparation of health care providers, and our biomedical science and engineering succeed in making the difference our state will need? To respond to an aging Maine, the public higher education system needs to address the needs of Maine people for continued learning along their career and life span — intentionally and with relevance. In addition, it is critical to bring in learners from outside of Maine who might then stay.

Writing about the future of technology seems unwise, as its affordances and foibles change daily. Coupling the “regular” ongoing changes in the technologies that dominate every aspect of our society, with the disruptive effects of ubiquitous access to generative AI, higher education may need to take the leading role in this arena. As Forbes’ Nic Micanovic (2023) writes, “[T]echnological innovations are the most powerful driver of prosperity and welfare in history.” In 2023, there were more than 15 billion devices connected to the Internet Of Things (IoT) worldwide, with this number expected to double to more than 32.1 billion by 2030 (Statista, 2024). In 2020 alone, 466 million people used the internet for the first time, and that number is growing 6% per year. And yet in 2022, 2.7 billion people – one-third of the world’s population – had no internet access (Signe, 2023).

Predictions about the use of generative AI suggest its ability to increase the global economy by trillions, save billions of work hours per year, help most workers be more productive in their jobs, change the nature of work, and accelerate learning (Chui et al., 2023). More than 37% of college students report having used ChatGPT for assignments (Intelligent.com, 2024). At the same time, the ethical and moral dilemmas it poses and concerns about the demise of liberal education are widely debated, along with whether technology will be a great equalizer or seriously exacerbate the already large digital divide.

For so many reasons, I believe a commitment to inclusion, access, and equity, and a recognition of the importance of the diversity that those dimensions bring to a university must also be central to our re-envisioning efforts. Every idea, proposal, analysis, and recommendation should use an equity lens as a frame. Deeply entrenched rationalizations and ways of doing business here, without bad intentions, can prevent us from being the inclusive and equitable institution we need to be in order to remain aligned with our land-grant roots.

The reasons for this commitment include a basic social justice argument and much more. Learners preparing to work in a global economy need to not only understand differences across peoples, cultures, governments, and values; they need every opportunity to learn through experiences of those differences in their education at UMaine. A third reason, promoted by researchers like Scott Page, is that the best solutions to challenging problems come when diverse perspectives, viewpoints, and experiences come together. And yet another reason ties all of these together: paraphrasing National Science Foundation Director Sethuraman Panhanathan, “[T]alent can come from anywhere [but] opportunity needs to be everywhere.”

Members of the UMaine Compass project (https://umaine.edu/compass/) proposed elements of a vision for the UMaine of tomorrow, and these three are resonating well with all groups:

These themes can be a framework for the change we must consider in our strategic re-envisioning as we reaffirm our leadership in teaching, research and public engagement for the next 160 years.

Conclusion

Universities lead society and support economic growth, social mobility, social engagement, and personal fulfillment. To do so in relevant ways means self-examination and change. The Strategic Re-Envisioning initiative (SRE) at the University of Maine is designed to enable that, as we ask the fundamental question:

What would the University of Maine look like if we were designing it today? That is the work of SRE.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the support and advice of several members of the University of Maine community in the preparation of this white paper, notably Debra Allen, John Diamond, Shelby Hartin, Bella LoRusso, Michelle Rogers and Kelly Sparks.

References

Chui, M., Hazan, E., Roberts, R., Singla, A., Smaje, K., Sukharevsky, A., Yee, L., & Zemmel, R. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. McKinsey & Company. mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier

Crow, M. M. (2022, June 6). Celebrating #NationalHigherEducationDay! Higher education is the key to unlocking individual potential [LinkedIn post]. LinkedIn. linkedin.com/posts/michaelmcrow_nationalhighereducationday-activity-6939714964223909889-Q8J5/

Gunja, M., & Gast, S. (2024, May 14). Centering students in our draft framework for the Carnegie Social and Economic Mobility Classification. Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/centering-students-in-our-draft-framework-for-the-carnegie-social-and-economic-mobility-classification/

Intelligent.com (2024, February 27). 4 in 10 College Students Are Using ChatGPT on Assignments. Intelligent. intelligent.com/4-in-10-college-students-are-using-chatgpt-on-assignments/

Maine Center for Disease Control. (n.d.). Rural health and primary care. Maine Department of Health and Human Services. maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/public-health-systems/rhpc/rural-health.shtml

Maine Climate Council. (2020, December). Maine won’t wait: A four-year plan for climate action. maine.gov/future/sites/maine.gov.future/files/inline-files/MaineWontWait_December2020.pdf

Maine Department of Administrative and Financial Services. (n.d.). Demographic projections. Maine.gov. maine.gov/dafs/economist/demographic-projections

Milanovic, N. (2023, May 16). Technology will change the world – Will the world change with it? Forbes. forbes.com/sites/nikmilanovic/2023/05/16/technology-will-change-the-worldwill-the-world-change-with-it/

National Student Clearinghouse. (2023). Student tracker for high schools aggregate report: Prepared for Maine Department of Education. maine.gov/doe/sites/maine.gov.doe/files/inline-files/2023%20Statewide%20Basic%20report_0.pdf (no longer available)

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2023). Current term enrollment estimates. National Student Clearinghouse. nscresearchcenter.org/current-term-enrollment-estimates/

OECD. (2022). Climate action slowed significantly in 2022 while severe weather events increased. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2023/11/climate-action-slowed-significantly-in-2022-while-severe-weather-events-increased.html

Reber, S., & Smith, E. (2023, January 23). College enrollment gaps: How academic preparation influences opportunity. Brookings. brookings.edu/articles/college-enrollment-gaps-how-academic-preparation-influences-opportunity/

Signé, Landry (2023, July 5). Fixing the global digital divide and digital access gap. Brookings. brookings.edu/articles/fixing-the-global-digital-divide-and-digital-access-gap/

Teague, L. J. (2015). Teague, L. J. (2015). Higher education plays a critical role in society: More women leaders can make a difference. Forum on Public Policy Online, 2015(2). eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1091521

University of Maine. (n.d.). UMaine Compass. umaine.edu/compass/

Vailshery, L. S. (2024, June 12). IOT connections worldwide 2022-2033. Statista. statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/

World Health Organization. (2023, October 12). Climate change and health. World Health Organization. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

World Population Review (2024). Most Rural States 2024. worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/most-rural-states