A Glimpse of Wilderness: Eagle Lake, Piscataquis County, Maine 1959/1960

By Will Reid

This is about a “renewed wilderness” that existed only briefly as such and is now gone. Even though it is presently considered “preserved,” the area is too accessible and heavily visited for anyone to experience what we did in 1959 and 1960.

Steve Bunker of Bucksport and I became good friends while at Bowdoin and shared many fishing and hunting adventures during 1956-1960. Two that stand out in my memory, however, are the fishing trips we took in May of 1959 and 1960 to Eagle Lake in Piscataquis County. Back then there was no I-95 to go north from Brunswick on nor were there any roads in Maine that we could take directly to the lakes at the head of the Allagash.

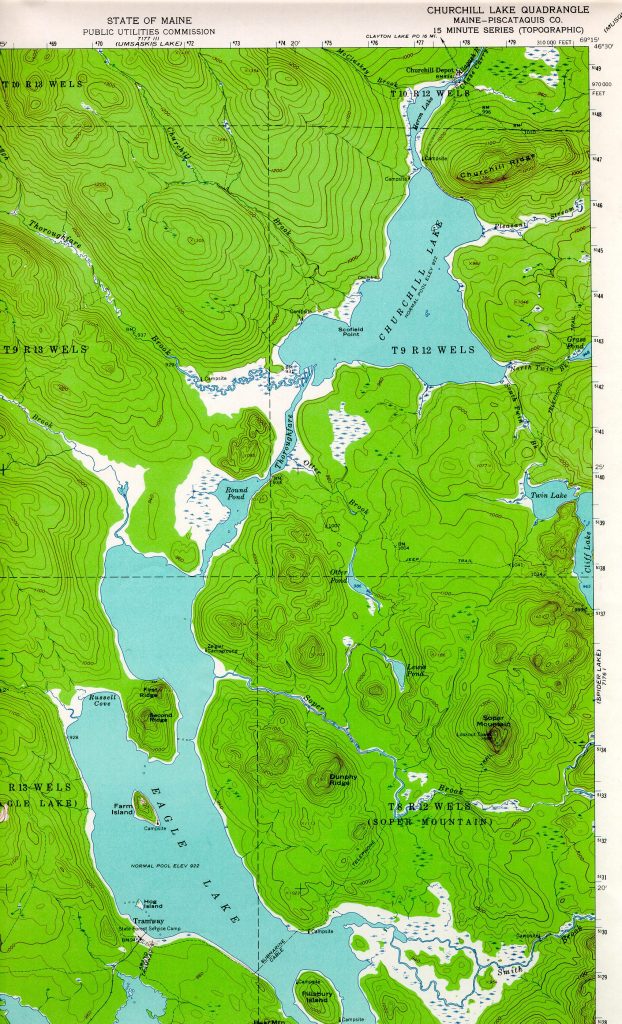

In 1959, we put a small canoe on top of the car, drove north through Jackman into Quebec and then back into Maine via either Lac Frontiere or Daaquam (don’t remember which crossing). No passports were needed back then! It was a rough drive over a gravel road still in the process of thawing out from the winter. Ours was the first 2WD vehicle that year to make it to Churchill Depot at the head of the Allagash. We were surprised to see that the dam had washed out (in 1958 as we found out later), but went ahead, loaded the canoe and paddled across Heron Lake to Churchill Lake, through Round Pond, and on to Eagle Lake (see the 1962 USGS Churchill Lake topo map). The water was low and the shore in places was a swath of mud and dry-ki (bare remains of dead trees lying on the former lake bottom that were killed many years ago by flooding due to the dam), Old peaveys were scattered here and there next to the lakes. We set up a canvas tent on the shore of Eagle at a site near Soper Brook and slept soundly. We awoke in the morning to a steady gale from the northwest and a lake of fierce whitecaps that continued day and night for four days. We couldn’t keep the tent up so we built a shelter out of the dry-ki on the shore. We had planned to live on the trout we caught but couldn’t get out on the lake to fish.

Soper Brook, however, was within easy walking distance because of the exposed shoreline, and we caught plenty of fine 10” to 17” brook trout each day from a pool below the falls not far from the lake. One day, while “searching for worms for catching our dinner” as Steve put it, he overturned a small rock along the shore near where we camped and found an 1846 penny! We still wonder who hid the penny there and why. Could it have been his grandfather who was a woodsman in that area in the late 1800s? Steve still has that penny. Finally, after sunset on the fourth day, the wind dropped and the waves subsided. We hastily loaded the canoe and paddled back to Churchill Dam where we slept on a small point between Round Pond and Churchill Lake. The wind came up full force again after dawn, but was of no consequence as we had made it back during the lull. We later learned that many others have also experienced the fierce wind and waves of Eagle Lake.

The following May we made the same trip through Lac Frontiere or Daaquam (again, don’t remember which crossing) and camped at the same spot near Soper Brook. This time we had a small boat with a motor, and with calm conditions we had no problem keeping the tent up. We had great fishing, catching lake trout on streamers right at the surface. We saw 50 to 60 deer and a few moose all at the same time in a meadow along Snare Brook across the lake. Some of the deer looked very weak, and a small one swam across the brook in front of our boat. We visited the south end of Eagle Lake where we were astounded to see two huge steam locomotives, a locomotive shed, and railroad tracks with trees growing up between the rails on the strip of land between Eagle and Chamberlain Lakes that was marked “Tramway” on our 1954 USGS Churchill Lake, ME topo map. The map (with our notes), which I still have, showed an abandoned railroad line going southerly to the north end of Chamberlain Lake, then continuing on the other side of Chamberlain along its west shore.

During those two trips we had only two visits from the outside world by people. One was a single engine plane that circled over us after we had built the dry-ki shelter in 1959, presumably to see if we were OK. The other in 1960 was by three Canadian fishermen in a small aluminum boat who landed hard on the shore, stayed briefly, and then departed.

I have done some research regarding the history of that area, especially about the railroad, to learn if things have changed in what seemed to us to be wilderness in 1959/1960. The following is what I found, including some conflicting information from different sources.

Extensive cutting was underway in that area as far back as the 1830s. Henry David Thoreau visited Eagle Lake (which he called Heron Lake or Pongokwahem) in July 1857, camping on Pillsbury Island, about five miles south of where we camped. By then there were logging roads, a farm (Chamberlain Farm), dams, and a canal (Telos Cut). By 1882 there was a road easterly of Churchill and Eagle Lakes all the way from Heron Pond to Chamberlain Farm that crossed Soper Brook. Thoreau also encountered high winds and waves on Eagle Lake. The flow of the uppermost lakes in the Allagash watershed, which originally included Chamberlain, had been diverted to flow into the Penobscot drainage. The dam at the northern end of Heron (not the Heron Lake of Thoreau) and Churchill Lakes had been built in 1846 to facilitate the passage of logs.

Eighty years later Edouard “King” Lacroix rebuilt the original dam at Churchill Depot at the outlet of Heron Lake in 1926 (or in 1925 by Great Northern Paper?). That dam raised the water levels in the upstream lakes, including Eagle. It was reconstructed in 1967 (or replaced 300 feet upstream in 1968?) and replaced in 1999 (or 1997?). The locomotives, tracks, and sheds we saw at the end of Eagle Lake were remnants of Lacroix’s Umbazookskus and Eagle Lake Railroad which replaced the tramway built in 1902. Great Northern Paper bought Lacroix out in 1927 and renamed the railroad the Eagle Lake and West Branch Railroad. It operated from 1927 to 1933. Lacroix also used Lombard Steam Log Haulers, which were also eventually abandoned in the woods.The Log Haulers were invented by Alvin O. Lombard of Waterville (patented in 1901). Haulers looked like a locomotive with a lag tractor tread. They replaced the four-horse teams typically used to move heavy sled-loads of logs. Lacroix’s Madawaska Land Company headquarters was at Churchill Depot at the Heron Lake/Churchill Lake Dam, where we left our car in 1959 and 1960. The road we traveled from Lac Frontiere was built by Lacroix in 1927 and was used by Helen Hamlin in 1937 to reach the then active village of Churchill Depot in order to teach school for three years. She, too, visited the “trout pool on Soper Brook for the May fishing”. Chief Henry Red Eagle (Henry Perley) mentions all of this in an article he wrote in the early 1950s – the strong winds, the Lac Frontier road, Soper Brook, the remnant of a small community, the dams and lumbering, LaCroix Lumber Co., and the remains of the railroad.

In 1966, the State of Maine established the Allagash Wilderness Waterway (AWW), which included where we camped and explored, “to preserve, protect, and enhance the wilderness character of this unique area.” Log drives were ending in the mid-1960s and road systems were expanding, resulting in an increase in recreational traffic. From 1967 through 1973, the number of AWW visitors doubled. An organization called the North Maine Woods (NMW) begun as an association in the early 1970s, developed into a non-profit corporation, and increased the size of its managed area. The development of the NMW was caused by an expanded road network and a greater demand by the public for recreation land. The NMW region is nearly three million acres belonging to over 20 owners and completely surrounds the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. The NMW does not consider the region to be a wilderness as there are over 2,000 miles of permanently maintained roads and several thousand additional miles of temporary unmaintained roads. Many roads are plowed in the winter for hauling wood. Areas once accessible only by foot, canoe or plane were opened up. The result was overcrowded campsites and even traffic jams. The Tramway area with the locomotives was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Over 4,300 people visited the AWW in 2018, with more than 1,600 of those visiting the Tramway Historic District. The AWW total of visitor days in 2018 was over 34,000.

Our 1959 and 1960 “adventures” are important to me because when I returned to Maine in the late 1960s after serving in the Air Force, I came to realize what we experienced no longer existed in Maine. The logging road network throughout the north woods was being greatly expanded, and cutting was taking place on a much greater scale and in places where it had not occurred before. Accessibility to the area had become much easier. There were roads on both sides of Eagle Lake and even a bridge (John’s Bridge) crossing between Round Pond and Churchill Lake. One did not have to go to Quebec to get there, and there was now I-95. More people were taking advantage of that easy access to visit the waterway.

The impressions of our fishing trips still remain very clear over 60 years later; the total darkness at night, no planes or satellites, and the stillness, other than the wind. Then it was a true wilderness, accessible only with effort, and with the remnants of a mysterious abandoned railroad having been taken over by the woods once again. Steve and I had previously camped out on Moosehead and Square Lakes and on the Moose River, but those places were much more accessible and heavily visited than Eagle Lake. None of those experiences gave us the same feeling of remoteness. I treasure more and more over the years how very fortunate we were to have seen that wilderness which existed only for a few decades between human disturbances. Neither of us has ever been back to Eagle Lake. All we have are recollections of what it was like over 60 decades ago (and an 1846 penny!).

Information Sources:

Appalachian Mountain Club. 1986. Allagash Wilderness Waterway, p. 156-170. In AMC River Guide: Maine, AMC, Boston, MA. 292 pp. + Appendix & Index.

Bennett, D. B. 2009. Nature and Renewal. Wild River Valley & Beyond. Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, ME. 223 pp.

Bennett, D. B. 2001. The Wilderness from Chamberlain Farm: A Story of Hope for the American Wild. ISLAND PRESS / Shearwater Books, Washington. 440 pp.

Bennett, D. B. 1994. Allagash: Maine’s Wild and Scenic River. Camden, Maine: Down East Books.112 pp. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/parks/publications_maps/AWWBroc/AWWRef.html.

Colby, G. N. 1882. Atlas of Piscataquis County, Maine. George N. Colby & Co., Houlton and Dover, ME. (online image from atlas)

Eagle, Chief Henry Red (Henry Perley). 1952. The Thunderous Wonderous Allagash, p. 26-35. In In the Maine Woods (booklet), Bangor and Aroostook Railroad Company, Bangor, Maine. 80 pp.

Hamlin, H. 1945. Nine Mile Bridge. Three Years in the Maine Woods. Down East Books, Camden, Maine. 233 pp.

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, Bureau of Parks and Lands. 2020. Allagash Wilderness Waterway Guide & Map. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/parksearch/PropertyGuides/PDF_GUIDE/aww-guidepdf. 02/29/2020.

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, Bureau of Parks and Lands. 2020. Allagash History. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/parks/discover_history_explore_nature/history/allagash/history.shtml

McPhee, J. 1975. The Survival of the Bark Canoe. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 114 pp. + A Portfolio of the Sketches and Models of Edwin Tappan Adney (1868 – 1950).

North Maine Woods. 1992. Sportsman’s Guide Map Regulations and Information. North Maine Woods, Inc. P. O. Box 421, Ashland, Maine 04732.

North Maine Woods, Inc. 2020. History of the North Maine Woods (NMW). https://www.northmainewoods.org/aboutus/history.html. 02/29/2020.

Parker, E. L. 1996. Beyond Moosehead. A History of the Great North Woods of Maine. Moosehead Communications, Inc., HC 76, Box 32, Greenville, Maine 04441-9727. 197 pp.

Pike, R. E. 1967. Tall Trees, Tough Men. An anecdotal and pictorial history of logging and log-driving in New England. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York. 288 pp.

Thoreau, H. D. 1857. The Allegash and East Branch. In The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau. The Maine Woods. 2004. Princeton University Press. Princeton and Oxford. 347 pp.

USGS. 1954. Churchill Lake, ME 15 Minute Topographical Map (annotated with our notes).

USGS. 1962. Churchill Lake, ME 15 Minute Topographical Map.

Warner, K. 1967. The Allagash. Maine Fish and Game – Summer 1967, p. 8 -11.