White Shark Migration and Taking Part in the Research Process with Patrick Tardie

By Camryn Sudimick, Writing Intern

White sharks are one of the most iconic species in the sea. While they have gained a fearsome reputation, researchers like Patrick Tardie, a Maine-eDNA undergraduate intern, argue they should instead be recognized for their vital role as apex predators in marine ecosystems. While white shark populations faced a decline in Northwestern Atlantic waters in the past, they are experiencing a rebound in recent years. This recent resurgence has sparked the interest of researchers like Tardie.

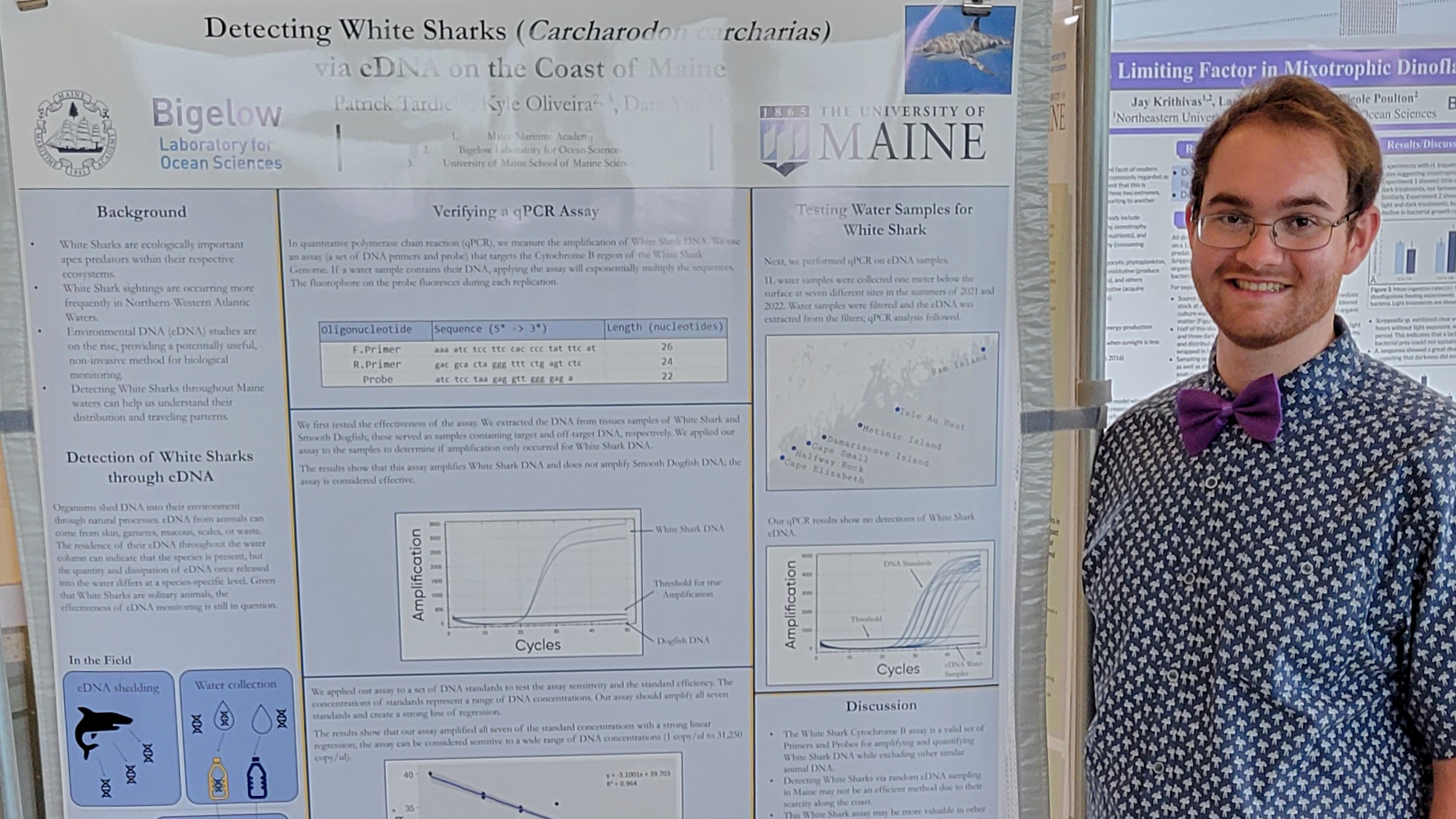

Tardie is a junior studying marine biology at Maine Maritime Academy in Castine, Maine. He spent the past summer working as an intern for the NSF EPSCoR RII Track-1 Maine-eDNA project at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences under the mentorship of University of Maine Ph.D. candidates, Kyle Oliveira and Dara Yiu. They worked to detect the presence of white sharks along the coast of Maine to better our understanding of white shark movements.

To do so, they used environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling, a method that involves analyzing genetic material that organisms shed into their environment. The researchers collected water samples from seven different testing locations along the coast of Maine, spanning from Cape Elizabeth to Ram Island. They then analyzed the samples to determine the presence of and quantify the white shark DNA. They tested for the validity of their qPCR assay with numerous tests and proved it was effective in detecting white shark DNA in water samples.

Despite applying an effective assay, no white sharks were detected in the samples. This led Tardie to the conclusion that random eDNA sampling may not be the most efficient way to detect white sharks and further experiments were needed. It’s worth considering that the water samples were collected from open waters. Tardie explained, “We can kind of extrapolate that eDNA is not a good method for detecting white sharks in open ocean waters.” This could be, as he suggested, because of the overall scarcity of white sharks along the coast of Maine.

This outcome prompted questions about a more efficient sampling approach, suggesting that obtaining samples from areas where white shark eDNA is more likely to be present in higher concentrations might be beneficial for validating the team’s methods. “With this type of study, I would have liked to work at some sites and get some samples where maybe, the day of at best, there was a white shark in the area,” he remarked. “I think that would help reach a better conclusion about the strengths or weaknesses of our approach.”

Tardie’s research is a part of Maine-eDNA’s “Species on the Move” project, which explores the movement of species throughout the Gulf of Maine. Although his focus is on white sharks, his research contributes to the larger effort to understand how and why species are shifting in response to the rapidly changing climate. Tardie highlighted the potential of eDNA, stating, “Using eDNA, we can potentially track the presence of certain animals in certain areas, which, if done with every species, offers an easier, less invasive, and less expensive method for tracking species.” Despite the absence of white shark eDNA in the results, this study is far from a failure. Tardie emphasized, “Just because my research didn’t bring out positive results, it doesn’t mean that it didn’t work. eDNA is on the rise, and there are a lot of questions regarding it. My part is just one aspect.”

While they may not have detected white sharks, it underscores the iterative nature of scientific research and the lessons that can be learned from what might initially seem like setbacks. Tardie’s work contributes to findings that will impact the state of Maine and its ecosystems. Researchers can use these insights to study this topic further and experiment with other methods and sampling approaches.

Research experiences like Tardie’s have long been the focus of EPSCoR programs in Maine like the NSF EPSCoR RII Track-1 Maine-eDNA project. Tardie and other students are placed at leading research institutions across the state like the University of Maine and the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. NSF EPSCoR funding makes these experiences accessible. These internships are made available statewide, including to students at emerging research institutions like the Maine Maritime Academy, providing students with the opportunity to learn from renowned researchers and develop both academically and professionally, while also making real contributions to research initiatives of importance to Maine and the country.