Implementing Biocultural Markers in Research Data Practices

By Caty DuDevoir, Writing Intern

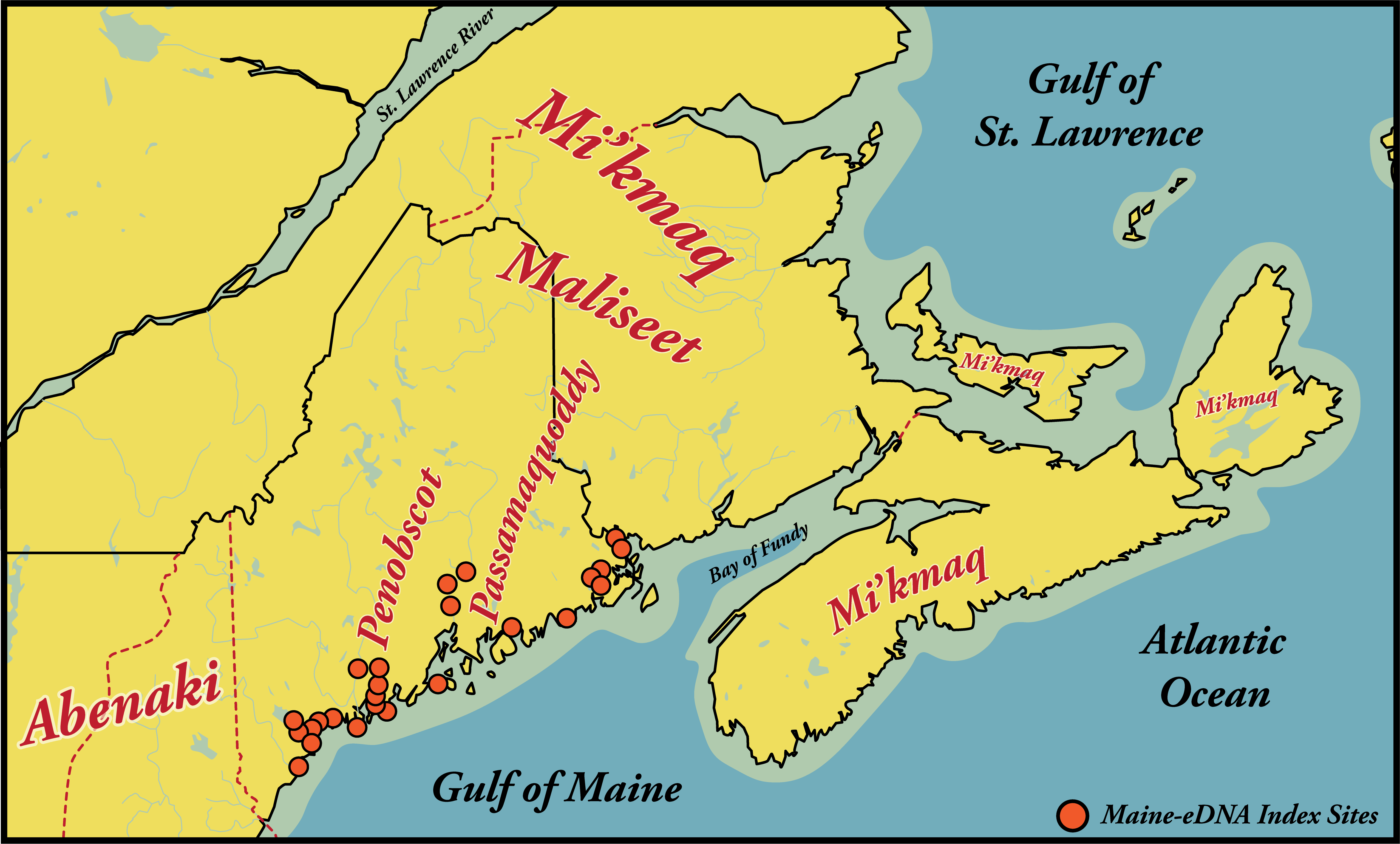

In any scientific and humanistic discipline, ethical collection of samples is a vital step in the research process. With a field like environmental DNA (eDNA), researchers sample soil, water, and organisms from the physical environments. The knowledge derived from them is collected on the land of Indigenous tribal nations, which comes with the responsibility to maintain both discussions with the local communities and care for the data collected. To help address this, the NSF EPSCoR RII Track-1 Maine-eDNA project, along with Maine EPSCoR and the Maine Center for Genetics in the Environment (MCGE) at the University of Maine (UMaine), announced an Open to Collaborate Notice in fall 2022. This signals the project’s commitment to working with and learning from the Wabanaki Nations (the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot) and other partners. This commitment is paired with the implementation of Biocultural Notices in the Maine-eDNA database, which are attached with each and every sample from when it is collected in the field, through the lab process, and into the database.

In the summer of 2021, Darren Ranco, UMaine Associate Professor of Anthropology and Coordinator of Native American Research, offered an ethics workshop that sparked the interest of multiple graduate students committed to ensure that data collection and storage practices were done in dialogue with local Indigenous groups. Later that fall, during a Maine-eDNA graduate course, Team Science for Maine’s Coastal Macrosystem, Erin Grey (UMaine Assistant Professor of Aquatic Genetics) and Andy Rominger (UMaine Assistant Professor of Ecological Bioinformatics) focused on introducing students to team-based eDNA research. Students collaborated with Local Contexts and Equity for Indigenous Research and Innovation (ENRICH), who facilitate Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels and Notices. Maine-eDNA Ph.D. candidate Jennifer Smith-Mayo and graduate student Beth Y. Davis, along with Melissa Kimble and Laura Jackson from UMaine Advanced Research Computing, Security and Information Management (ARCSIM) who were developing Maine-eDNA’s database, worked with Ranco and Rominger to maintain discussions around eDNA data that contains cultural rights information. The team continued to work with Local Contexts and ENRICH following the graduate course to implement Biocultural Labels and Notices into the Maine-eDNA dataflow.

“This work is new and challenging and reflects a deep engagement with research. It is a responsibility and requires more training for faculty and students,” Ranco remarked. “That said, it also opens up so many opportunities for win-win scenarios for both researchers (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and Tribal Nation citizens. I also want to point out—at least since the MOU in 2018—the University of Maine has become a leader in this work.” Ranco began working with Local Contexts roughly seven years ago to develop Traditional Knowledge Labels in his own research and as a citizen of the Penobscot Nation.

An international collaborative, Local Contexts aims to create conversations and methods that focus on protecting intellectual property and digital data of Indigenous groups within research spaces. Smith-Mayo explained, “The Local Context Hub is a digital hub and repository. It allows Indigenous communities to adapt Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels to their needs and share them safely with institutions, researchers, and data repositories.” Institutions and researchers create Notices and generate conversations around Indigenous interest with the data. Notices signal that the institution is committed to open dialogue with Indigenous communities and recognize Indigenous interests in data collection and their rights to share in the governance and derived benefits of those data. When institutions and researchers apply for a Notice to the project, local Indigenous groups will decide how and when a Label is assigned. The application of a Label may indicate that the data is only for research or outreach, but a different Label may indicate something is open to commercial use as decided by Indigenous communities.

Davis explained that the scientific process does not have to be entirely one ideology or another but rather a more nuanced, developed approach to these ethical topics. Modern data practices push to share information and make it easily accessible, but it also ignores the potentially harmful effects that this mindset has on communities. Local Contexts raises the awareness of harm that extractive practices have on people.

“Scientists are connected to the rest of our communities, animals, plants, and humans. We are not isolated,” Davis said. “The pathway that this opens up to us is just a better way of communicating and collaborating, and bringing awareness with ourselves and communities with the work we are doing and the context in which it lies.”

Engaging in this work does not mean inequalities and injustices are remedied, but it is a step in the right direction.

“They signal the right of Indigenous communities to define the use of information, collections, and data, including digital sequence information…generated from biodiversity and genetic resources that are associated with Indigenous traditional lands or waters,” Smith-Mayo said.

In recognizing that DNA is a living organism, there is a level of respect and responsibility that comes with collecting and analyzing it. Development of conversations, building relationships with Indigenous communities, and sharing data in an ethical way are steps in giving authority back to Indigenous people. “This work has made me think about what we are doing as researchers, how we are conducting it, and what kind of relationships we have with the people and the non-humans we coexist and live with,” Smith-Mayo said.

While this is only a step in the right direction, the Maine-eDNA project can help serve as an example to others and introduce this data approach to Maine-eDNA participants’ other work.

“It is a clear expression that these parts of the University of Maine take seriously the ethics and responsibility of doing research in Indigenous homelands, in collaboration with Indigenous Tribal Nations and Citizens,” Ranco said.