Studying tick-borne diseases in an iconic native Maine species: Moose

Winter ticks are causing severe illness in Maine’s iconic moose population. A team of University of Maine researchers examine the biophysical and social impacts of ticks in a uniquely collaborative project.

Merging two different sciences into one study.

Pauline Kamath, an assistant professor of animal health, Sandra De Urioste-Stone, assistant professor of nature-based tourism and Anne Lichtenwalner, director of the cooperative extension veterinary diagnostic laboratory, are faculty overseeing the interdisciplinary research project centered around ticks. They are investigating the prevalence of tick-borne diseases in moose, and ticks on moose while also measuring public perception of tick-borne disease frequency.

“We are using an interdisciplinary approach to look at whether the perceived risk of infectious disease in key stakeholder groups aligns with the actual risk of disease from moose and their ticks,” Kamath said.

Kamath, Urioste-Stone and Lichtenwalner are guiding undergraduates Kyle Alamo, Jaycob Bowker, MacKenzie Conant, Carly Dickson, Asha DiMatteo, Kristie Pinto and graduate student James Elliott. The students are from different schools of science at UMaine and are learning how to collect and process data.

This is one of nine currently funded Interdisciplinary Undergraduate Research Collaborative (IURC) projects. It combines two different fields of science into one study. Urioste-Stone is focusing on public perception. Kamath and Lichtenwalner are testing for two tick-borne illnesses in the lab. They are testing for the bacteria associated with Lyme disease and Anaplasma bacteria, which attack red blood cells.

“This has been an incredible experience for learning to work with researchers from different scientific areas to try to solve the same problem,” Kamath said. “It has also helped us to overcome barriers to communication. We have learned how to speak to each other in common language.”

Hands-on learning in a supportive lab environment.

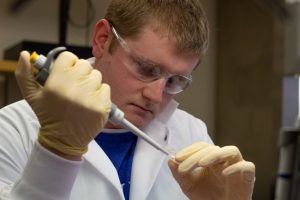

Carly Dickson, a zoology undergraduate from Fairfax, Virginia, worked in the lab with Kamath isolating tick and moose DNA.

“I worked in the lab all summer conducting genetic lab work to test whether moose were infected with bacteria,” Dickson said. “Certain species can infect humans and cause anaplasmosis.”

Dickson started the project with little lab experience. With Kamath’s guidance, she learned how to extract DNA and read the results.

“When I first met Carly, she had no prior experience in genetics or molecular techniques in general, but she had an exceptional drive to learn and impressed me with her ability to master new skills in a short period of time,” Kamath said about teaching Dickson to work in the lab.

Dickson intends to continue her education to earn a Ph.D. so she can develop her own research. When she started working in the lab her interest in genetics, disease ecology and environmental health peaked.

“I am so lucky to work in this lab. Everyone in the lab is enthusiastic about the work they do and highly supportive of one another” Dickson said. “After I graduate, I hope to go to graduate school to continue working in this field.”

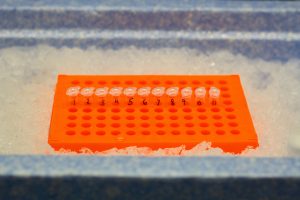

- Samples of DNA wait to be tested by grad student James Elliott

- James Elliott works with DNA samples in the Wildlife Disease Genetics Lab

Students obtain skills to analyze data.

Asha Dimatteo-Lepape, an ecology and environmental science and parks, recreation and tourism major, is from Brattleboro, Vermont. She is developing questions for a survey about public perception of risks from tick-borne diseases and how it affects the moose population.

“I’m trying to understand the risk perceptions that people have associated with winter ticks on moose in Maine, and their interactions and how it could impact human health and recreation opportunities and the economic implications,” Dimatteo-Lepape said.

Dimatteo-Lepape has started interviewing people in the Native American community near UMaine. She is also talking with hunters, guides and other people who work in industries affected by moose. Once the research develops further it will expand to broader groups in the community.

Dimatteo-Lepape learned how to interpret data from qualitative research, which explores why a certain phenomenon happens. She developed skills in collaborating with people across different platforms in science.

“I came into this project not really knowing too much about qualitative research or data analysis. Working on this project has given me a great skill set and a really great platform for working in qualitative research,” Dimatteo-Lepape said.

A better understanding of Maine moose populations.

Research on tick-borne diseases in Maine moose populations hasn’t been studied very closely in the past. Once this research project is complete it will shine a light on how these diseases are affecting moose in Maine. Kamath says this research will help the state make informed decisions for disease management and wildlife preservation.

“Moose are an important natural resource for both tourism and hunting. People come to Maine from all over the country hoping to see a moose. Hunting also brings in a lot of money to Maine. Therefore, having a better understanding of how tick-borne diseases in winter ticks can affect the moose population is essential for protecting this valuable natural resource,” Kamath said.

Written by Kendra Caruso

Media Contact: Christel Peters, 207.581.3571