Sandweiss, team in Peru study possible evidence of ancient human warfare

Nestled on the Peruvian coast, the Ostra Collecting Station (OCS) is part of a complex of archeological sites that provide an amazing glimpse into the lives of the people who lived there approximately 6,000 years ago.

OCS is cradled between the shores of the Pacific Ocean and the Andes mountain range. Odd shells and fish discovered at the site provide insight into the very different environment of New World inhabitants of the era.

Dan Sandweiss, University of Maine professor of anthropology and climate studies, was the first to investigate the site as a graduate student in 1980. Carbon dating indicates the samples he collected are just over 6,000 years old.

The remains, as well as geological surveys, reveal the site was perched atop a rocky ridge on the shore of the South Pacific Ocean. It is believed the ancient inhabitants peacefully fished, hunted, gathered and farmed.

Or perhaps, not so peacefully.

Ancient evidence of warfare

In 1983, Canadian archaeologist John Topic discovered artifacts of a different nature: strategically placed piles of what appear to be ammunition – stones modeled for slingshots.

Finding of ancient weaponry was a bombshell. But a big question remained – were these slingstones as old as the nearby site?

If the stone piles date back to the same time period of Sandweiss’ initial finds – 6,000 years ago or more – it would indicate humans in the New World were at war thousands of years before what is currently believed.

And it might revise the history of the New World and perhaps shed light on human nature.

“If we’re right, these data are absolutely unique for determining the antiquity of warfare in South America,” says Sandweiss, principal investigator of the project.

Unique because this would be the oldest evidence for warfare in the New World and it would push back by thousands of years when experts believe warfare began in this part of the world.

It also would lead experts to reassess human conditions for warfare. Are humans programmed to engage in lethal violence against one another? Or only when the situation demands it for survival?

Returning to Ostra

Because it was located directly on the ancient shoreline, Sandweiss and UMaine collaborator, anthropologist Paul “Jim” Roscoe, theorize the Ostra fortifications could have protected the inhabitants along the narrow coastal strip between the mountains and the sea.

As the ocean receded from the shore over the years, the need for coastal defense was eliminated and could be the reason why the site was left abandoned in such pristine condition, says Sandweiss.

He had to return to Ostra to see the new findings for himself.

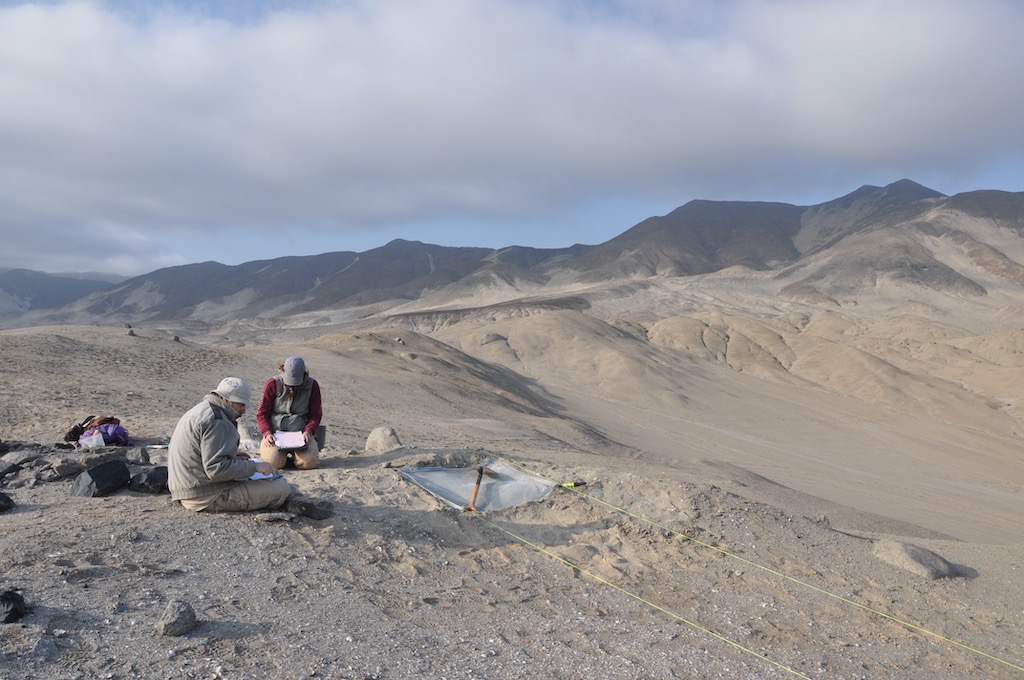

Once more in the shadow of the Andes on the Peruvian coast, Sandweiss and an international team of researchers began a renewed look into the lives of the ancient people who once lived – and may have fought – at Ostra.

Along with Sandweiss and Roscoe, the team included geologist Alice Kelley and graduate student Emily Blackwood – also from UMaine. UMaine alumna Cecilia Mauricio, an assistant professor at Catholic University in Lima, directed the project.

Gloria López joined the team in Peru from the CENIEH in Burgos, Spain, to collect samples from the stone piles for state-of-the-art OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence) dating.

According to Sandweiss, OSL is a new technique that measures the time elapsed since a grain of sand was last exposed to sunlight before its burial. A signal is captured in the lab from the samples and measures the accumulation of electrons – which can then be analyzed to determine the age of the samples. This is the only way that the stone piles might be dated, and it has only recently become available.

Blackwood used the field work to develop methods for creating virtual reality experiences from archeological sites as part of her dissertation work. She is using the data collected during the trip in a joint effort with UMaine’s VEMI Lab to develop software in hopes of finding a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable way for researchers and visitors to “see” ancient sites like Ostra.

The OSL results will take time as López tests 12 samples for comparison.

Until then, the question remains: Are humans prone to warfare? Or could the future of human civilization have a chance for peace?

The answers could be found in ancient Peru.

Media Contact: Christel Peters, 207.581.3571

“Determining the Antiquity of Warfare in South America” has been funded by the UMaine Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, a grant from the UMaine Faculty Research Funds, as well as support from the CENIEH Lab in Burgos, Spain.