Woven in Tradition: Navajo Textiles

Among the Hudson Museum’s holdings are examples of Navajo textiles dating from the late-Nineteenth Century to the present. These textiles came to Maine as souvenirs of visits to the Southwest, as décor for homes or rustic camps or acquisitions made by those who collect Navajo textiles. These works by Navajo (Diné) weavers reflect deeply rooted textile traditions that celebrate harmony and beauty as well as outside influences on their art by traders, Southwestern Art patrons, and buyer preferences.

This exhibit included several textiles collected by Mabel Weeks, who visited family in Thoreau, New Mexico in 1906, another was sent back to Maine in 1904 by the donor’s grandparents, while others were collected by individuals who admire the beauty of these pieces.

Coal Mine Mesa Raised Outline

c. 1992

This style of weaving dates to the revival of weaving at Coal Mine Mesa in the 1960s. Like all Navajo textiles the pieces is tapestry woven, but rather than weave over each warp thread the weft floats over two warps rather than one.

Museum Purchase

HM9710

Single Saddle Blanket

c. 1950

Anonymous Lender

Meander Pattern Rug

c. 1920

This textile was acquired by an individual who worked for the Transcontinental Railroad which ran from St. Louis to San Francisco.

Donated by John Pickering

HM6899

Single Saddle Blanket

c. 1990

Anonymous Lender

Germantown Rug

c. 1900

This textile was acquired by Cleveland Kennedy in 1914 from a weaver in the desert of the Hogback Ridge, near Gallup, New Mexico. He sent this textile and another by American Express to his parents, John and Mary Kennedy in Bucksport.

Donated by the family of Cleveland and Charlene Kennedy, Jr.

HM9670

Saddle Blanket or Child’s Wearing Blanket

c. 1880-1890

This textile incorporates both homespun and Germantown yarns.

Brian Robinson Collection

HM9268

Germantown Pillowtop

c. 1900

Between 1870-1910, commercially spun and dyed 3- and 4- ply yarns manufactured in Germantown, Pennsylvania were used by some Navajo weavers. Because of the yarn’s expense, traders supplied it to only the best weavers in their area. They hoped that by providing weavers with ready-to-use yarns, their weavers would be able to produce more textiles. Although Germantown pieces were later frowned upon because of their “eyedazzling” use of color, today they are valued for their technical excellence.

Ex. Portland Society of Natural History

HM5096

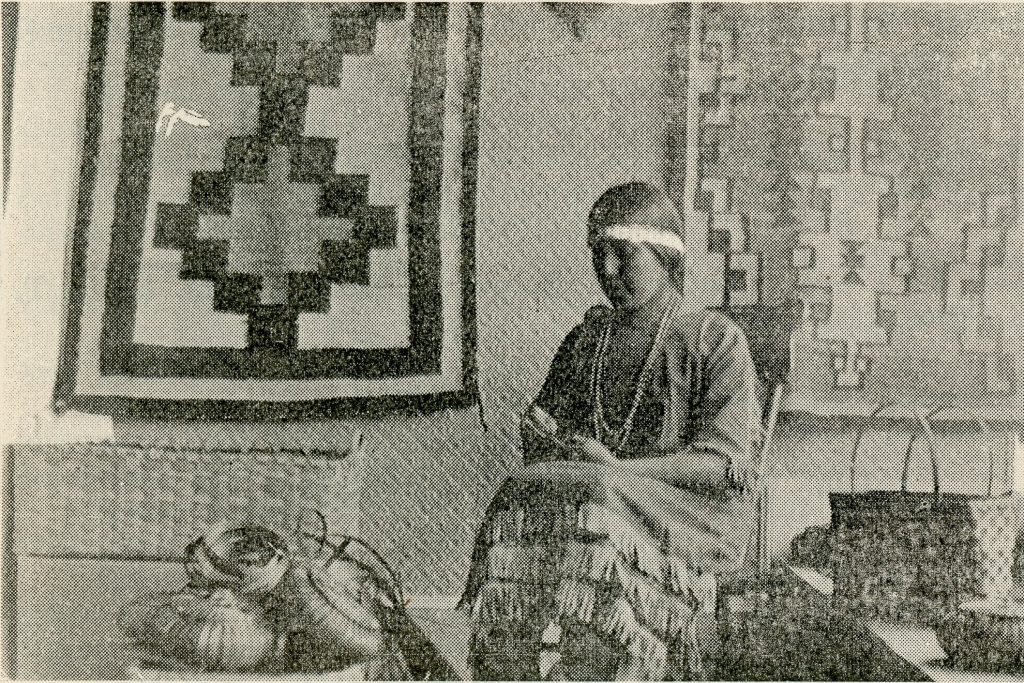

Image taken by Mabel Weeks of a Navajo Woman, Mrs. Ben Hudson, weaving a pillowtop

Ex. Portland Society of Natural History

HM7566

The Whirling Logs design symbolizes a Navajo

legend, in which the Yei (supernatural beings)

communicate knowledge to Nayenezgani, a

culture hero. The legend recounts

Nayenezgani’s journey down the San Juan

River in a dugout canoe. During the trip when

he reaches the point where the San Juan River

and the Colorado River meet, he encounters a

whirlpool. In the whirlpool, he finds a whirling

cross with two Yei figures seated on each end

of the cross, creating the Whirling Logs

symbol.

Germantown Sampler on a Loom

c. 1900

Traditionally weavers did not leave textiles unfinished, but these works were popular with visitors to the Southwest.

Martha J. Stevens Collection

HM2891

Miniature Weaving Tools

c. 1990

Anonymous Lender

Gallup Throw

c. 1930-1950

These textiles were woven on a loom using Native yarns woven on cotton warp. When finished the warp at the top of the textile was cut and knotted. These textiles were popular and inexpensive souvenirs for visitors to the Southwest.

Spinner Collection

HM8484

Two Grey Hills Rug

c. 1960

Two Grey Hills textiles are woven from undyed natural wool colors – black, gray, beige, brown, and cream. They are finely woven and often incorporate diamond designs.

Donated by Richard and Arlene McCrum

HM6434

Chinle Revival Banded Textile

c. 1920-1930

This textile shows the influences of Mary Cabot Wheelwright, a summer resident of Mt. Desert Island. Wheelwright was an enthusiastic patron of Native American Art and founded the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Assisted by her niece Lucy Cabot, a dye expert, she sought to encourage a return to vegetal dyes and simple striped patterns. The borderless rugs that she promoted at Chinle became quire popular in eastern circles. The muted gold and brown banded textiles served as reminders of the Southwestern landscape and complemented interior decorating trends of the 1920s and 30s.

Anonymous Lender