Social Context

Art historians and archaeologists believe much information about ancient West Mexican society is encoded within shaft-tomb figures. Figures show how people looked, what they wore, how they interacted with other people, what objects they carried, how they decorated their bodies, and what activities and rituals they performed. Certain combinations of posture, clothing, and gender appear together in many figures but other combinations do not. The groupings of traits are important because potters made the figures for specific uses by a particular audience. Studying the figures’ characteristics helps us understand what some social and artistic conventions were in West Mexico.

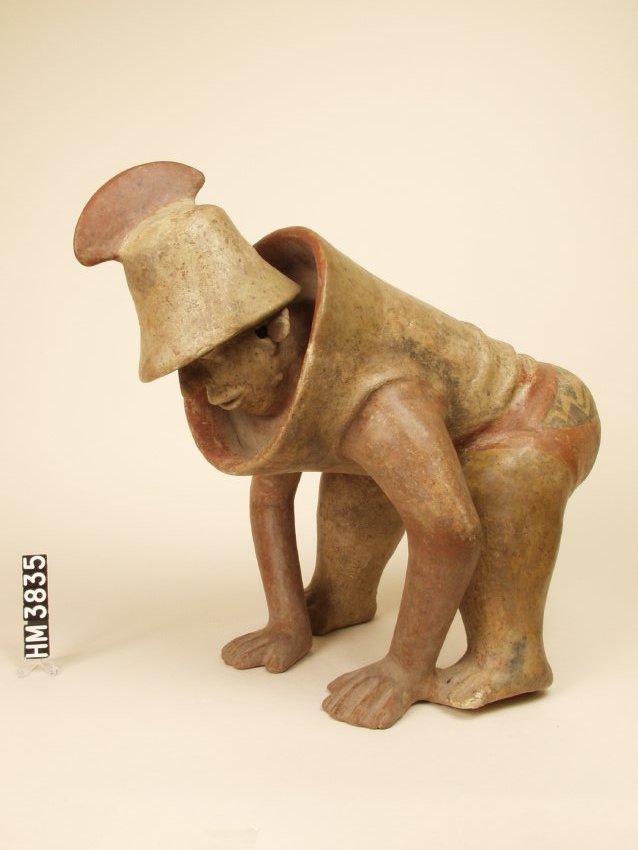

Jalisco Ceramic Figure

200 BC – AD 300

Ameca-Etzatlán Style

The posture is unusual, as is the decorative treatment of the warrior´s shorts.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM3835

A person in West Mexico was born with a certain social standing, or status, related to gender and family. People achieved other statuses during life because of increasing age or skills. Tomb figures commemorate rites of passage people went through and social statuses they enjoyed while alive. The figures acted as passports, allowing the dead to take their statuses into the realm of death. Changes in the character of ceramic figures reflect social changes accompanying the rise of the Teuchitlán tradition after A.D. 200. Earlier figures have portrait-like qualities and may be representations of actual people. Later figures, such as those of the Late Comala phase, are more rigid and formalized symbols of the roles people played in society, such as ruler or priest.

An important status for females came with reaching child-bearing age. Many figures of nude women have swollen bellies, are seated or kneeling, and appear to be moaning, as if in the act of giving birth. They frequently are painted or incised around the hips to emphasize fertility. It is uncertain whether this decoration is symbolic or represents actual painting or tattooing. The majority of small solid figurines are obviously female and share many of the large figures’ symbols of fertility. Some bed figures of women in the throes of difficult childbirth are accompanied by howling dogs. Ceramic dog figures appear in some tombs, so this may reveal a connection between birth and death in the West Mexican belief system.

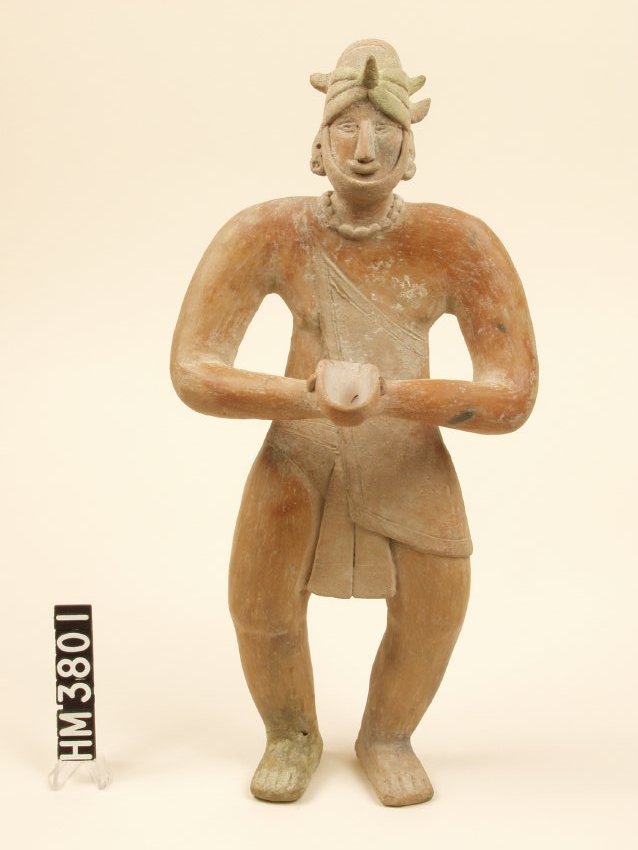

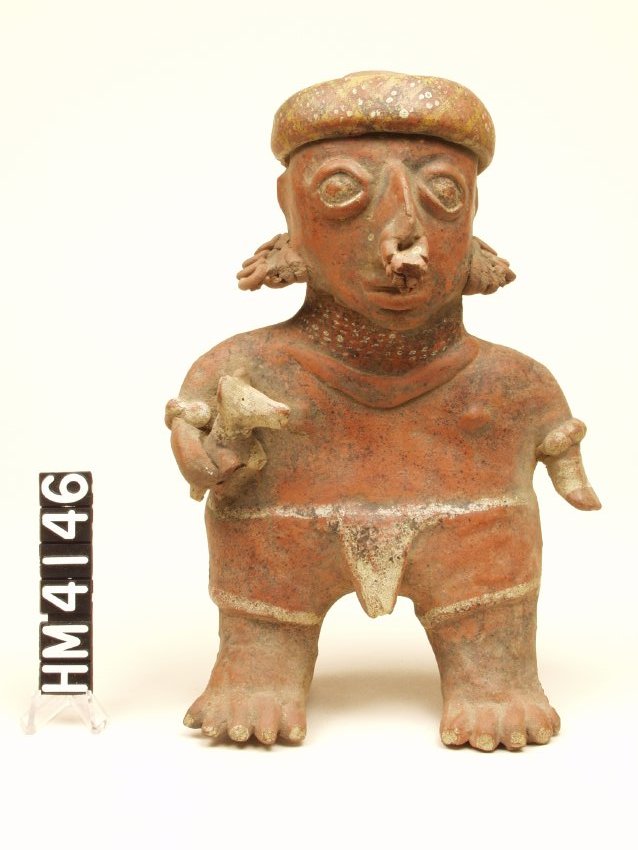

Male statuses commemorated by tomb figures center on achievement, such as being a warrior or ball player, or on ritual and political offices. The clothing and paraphernalia worn or the objects held usually provide clues about what status is depicted. Same-sex pairs with identical facial features may represent twins, important in Mesoamerican religion. Other pairs, where both individuals are dressed alike but one has teeth and the other lacks them, may show different life stages the person passed through.

Art historians and archaeologists describe male-female pairs of figures as “marriage pairs.” Often both figures are smiling, seeming to commemorate either the act of marriage or the existence of a happy union. They are typically very similar in size, construction, and decoration, differing mainly in clothing worn and objects held. Some marriage pairs are joined together, with one person having an arm affectionately around the shoulders or waist of the other. Physical anthropologist Robert Pickering suggests that the figures not physically joined actually represent the separate statuses of different people buried in the same tomb rather than marriage, since male figures lie near male skeletons and female figures are adjacent to female skeletons in tombs.