The Underworld

Iconographers (symbolism experts) have interpreted many images on ceramics as being scenes related to the Postclassic Popol Vuh, or “Council Book,” of the highland Quiché Maya. Although separated from Classic Maya scribes by 500 years, the story line of the Popol Vuh corresponds well to the images on ceramics. Many of the ceramics most convincingly associated with the story were produced near the southern highland site of Chamá, in the Chixoy drainage, during the late 7th to early 8th centuries. Black-and-white chevron designs at the rim and base characterize polychrome Chamá ceramics. Texts on Chamá ceramics tend to be short and to contain false glyphs called “pseudoglyphs”. This may mean that they were produced by only partially literate artisans or for more than just the elite segment of society. Chamá was located near the traditional entrance to the Underworld.

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 250 – 900

Classic Highland Guatemala

The Hero Twins turned their malevolent half-brothers into monkeys. The two Monkey-man Gods, Hun Batz and Hun Chouen, face each other on this vase. Prototypical scribes, they wear headgear with traits of both the scribe’s “Spangled Turban” and Pawahtún’s net headdress. One holds a pen and shell inkpot in his hands. The white scalloped shapes separating the figures appear to be stylized conch-shell inkpots. A restorer used pieces from another vessel in reconstructing this vase.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1196

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Chamá

The Young Maize God and his twin are separated by a single glyph on this vase. The Young Maize God was a patron deity of scribes and represented rulership. One Hunahpu and Seven Hunahpu descended to Xibalba, lost their lives and then were resurrected by the Hero Twins, sons of the Young Maize God.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1205

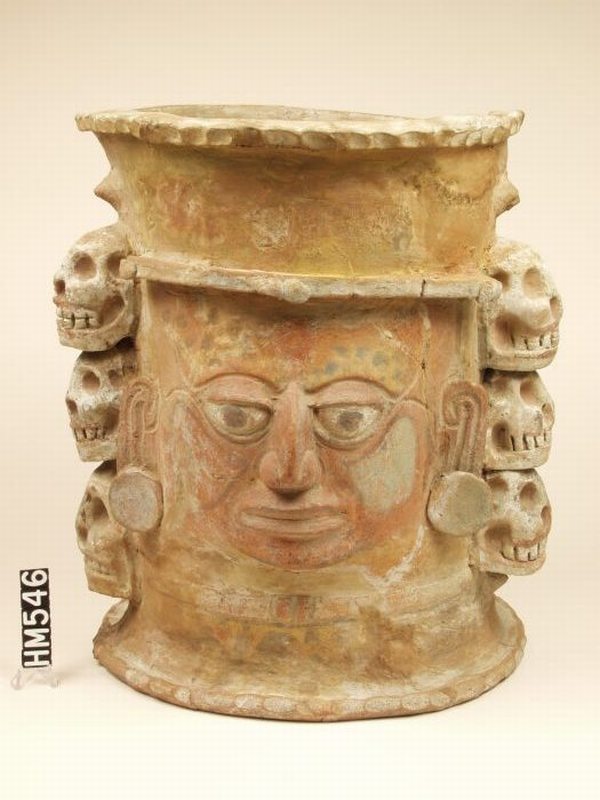

Maya Funerary Urn

AD 250 – 900

Classic Highland Guatemala

The central face, with its patches of jaguar skin on the forehead and large earflares, belongs to Xbalanque, one of the Hero Twins of the Popul Vuh. The three skulls on each side of the face emphasize the vessel’s connection with the Underworld.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM546

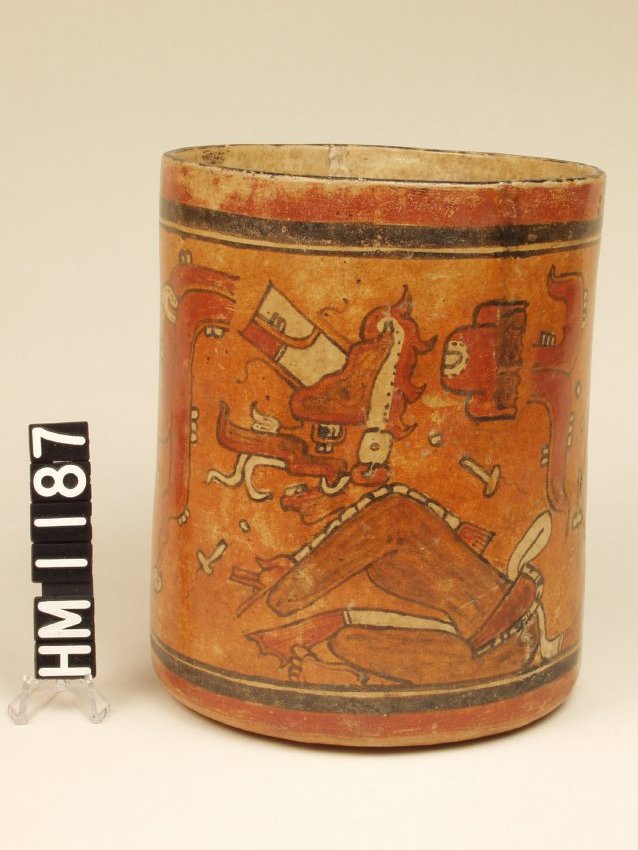

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Alta Verapaz

Two figures representing K’awil (God K) sit among symbols of Xibalba, including bones. Second born of a trio of gods called the Palenque Triad, this god has a zoomorphic snout and a smoking mirror penetrating his forehead. K’awil is associated with bloodletting rituals, kingship and the summoning of ancestors.

Click here to view a roll-out view of the entire vase.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1187

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Alta Verapaz

Two panels contain identical figures resembling Insect God B of the Underworld. They have large god eyes, open mouths with prominent teeth, snouts resembling insect proboscises, god markings representing mirrors on the arms, circular ear ornaments with long flap-like extensions on the back and crosshatched headdresses with long extensions from which quetzal feathers hang. Each carries a glyph in his hand. The two glyph columns are executed in a squared-off style.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1190

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Chamá

The two figures separated by glyph panels possess the human body and animal head of the Fox God, one of the denizens of the Underworld. Each wears the netted headdress of Pawahtún, to whom the Fox God was subordinate. The two figures face each other, making identical hand gestures. Speech scrolls emanate from their mouths, as if they are conversing. The Fox God was a patron of scribes or sculptors.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1177

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 250 – 900

Classic Alta Verapaz

Although incised, this vase is said to be from the Chamá area, an identification supported by the chevron band at the base. Two Death’s head skulls are separated by long bones. A band with repeated glyphs encircles the rim.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1185

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Chamá

The Young Maize God (Hun Nal or One Hunahpu) and his twin brother, Seven Hunahpu, perform a dance on this vase. They wear elaborate headdresses, on the front of which is a variant of the Jester God, personification of the royal headband. Panels containing textiles separate the dancers. This vase was restored by Lee Moore, who later repainted an Early Classic vessel with its image, creating a fake which confused experts for years.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1183