Palace Life

Scribes (called ah ts’ib, or “he of the writing”) were probably the literate younger sons of nobles not in the direct line of inheritance for offices and wealth. They lived in elite palace compounds and worked in royal workshops. Their job was to produce objects for use in palaces and rituals and as elite gifts. Given their background and patrons, it is not surprising that scribes painted scenes of palace life and elite rituals and ignored commoners when they depicted the world of humans.

Hieroglyphic texts are an integral part of many ceramic vessels. Epigraphers (writing experts) have identified a formulaic text known as the Primary Standard Sequence, which is usually located just below the rim of some pots. The PSS generally begins by dedicating the act of painting, a surface treatment which makes the completed vessel proper, records the vessel’s original contents, names the owner for whom it was made and sometimes ends with the signature of the artist. Not all sequences of glyphs below the rim are the PSS. Texts which discuss the images on a pot appear as short passages within the scene or, occasionally, replace the PSS.

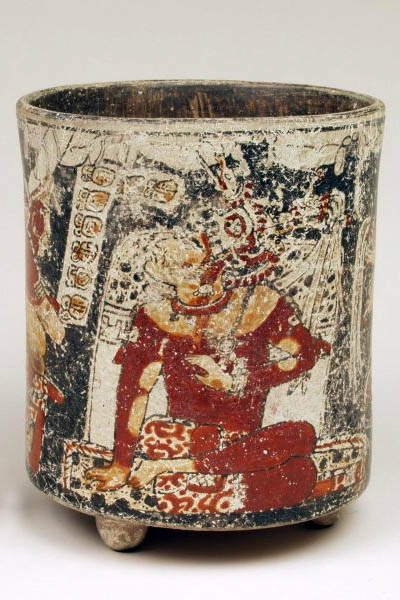

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Jaina

In a palace scene, a lord sits cross-legged on a jaguar skin, surrounded by four attendants. The ruler wears an ornate headdress containing a large-billed bird, earflares and a necklace. The artist made an attempt to convey depth by overlapping the two figures on the ruler’s right. Of the figures on the ruler’s left, one is kneeling with his feet turned in an unnatural position and the other is standing, but is cut off at the knees. The ruler and his attendants are marked by body painting. Above the figures is draped cloth with an intertwined serpent.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM532

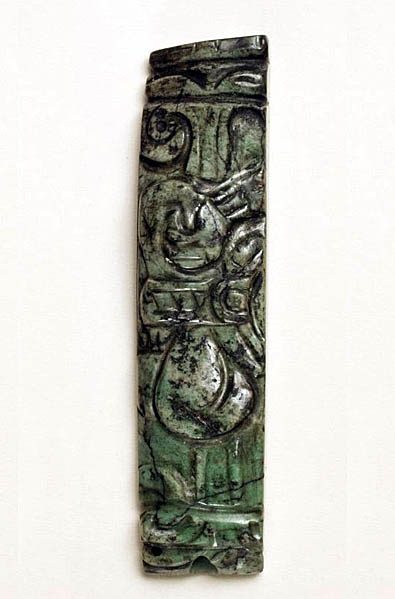

Maya Greenstone Pendant

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Ulúa Valley

Possibly originally from the important Maya site of Copán, this pendant was found in a tomb outside of the Maya area with an effigy metate (grinding stone) from Costa Rica and eight ceramic vessels (one of which is in the “Natural World” section of this exhibit). The figure of a ruler is carved into the surface.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM792

Maya Ceramic Figurine

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Jaina

The spondylus shell ornament around this figure’s neck identifies him as a middle-level court official. A member of the nobility, he has an artificially modeled nose and a deformed head with a sloping forehead, considered desirable traits by the elite. He also has marks representing facial scarification or painting, which the Maya used to change their appearance for different rituals. His red face and tattered clothing probably indicate that he has recently undergone a sacrificial ritual.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM4627

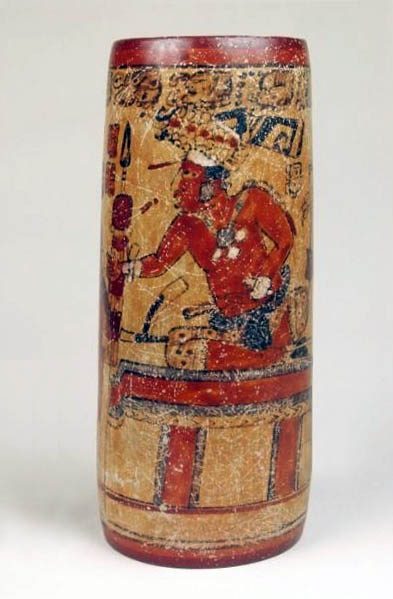

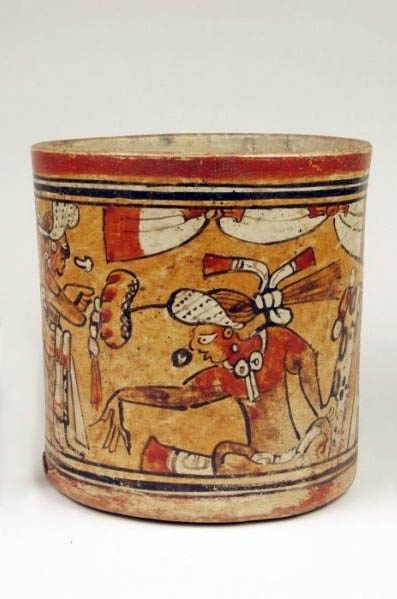

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Mexico-Guatemala Border Region

In this palace scene a ruler sits tailor-fashion on a throne, surrounded by attendants. He wears a spangled turban-type headdress with a jawless serpent head attached to the front. At the rear of the turban is a roll of cloth decorated with geometric motifs. Around his neck is a pectoral with attachments, in his ears are ornaments and around his midsection is a jaguar skin. Two of the attendants are armed with spears and the third holds what may be a bouquet, above which hovers a bird.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1172

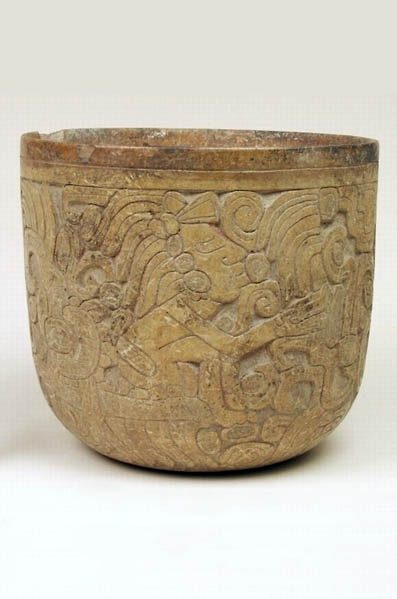

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 250 – 900

Classic Alta Verapaz

The central figure is a ruler with a Serpent Bar in his arms. Rulers held these scepters against the chest with the hands in a formal wrist-to-wrist position. In Mayan languages the words for “sky” and “snake” sound alike, so the Serpent Bar symbolizes both the sky and the Vision Serpent, as well as the act of conjuring the gods through vision rites. It refers to the important function of the king as an intermediary between the natural and supernatural worlds.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1175

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Chamá

The glyphs are executed in a disjointed and even distorted style. In one place, the day sign kawak has the number 14 with it as a date, which is impossible in the Maya calendar, since the days never have coefficients greater than 13. The artist who created the vessel may have been only semi-literate and may have intended the vase for persons of non-elite status.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1178

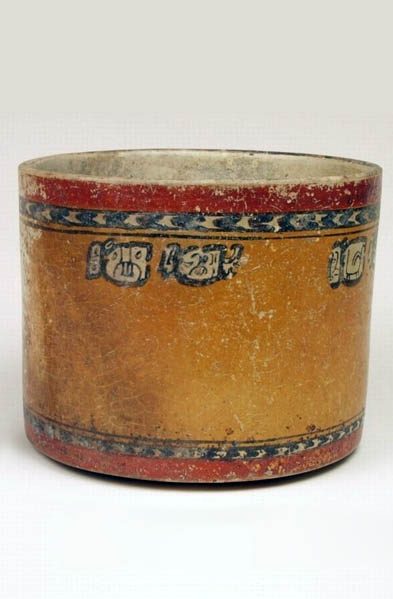

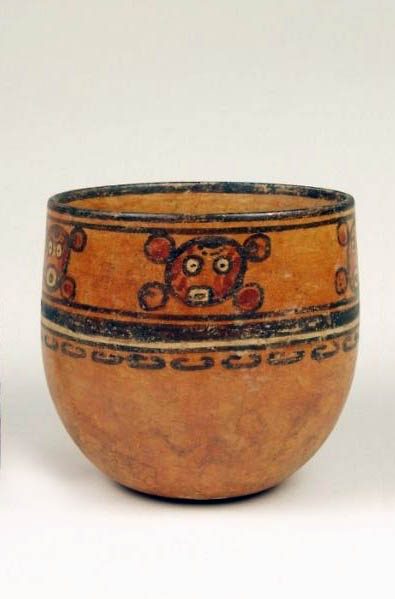

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 600 – 900

Late Classic Petén

A series of stylized heads taken from the ahaw glyph runs in a band around the body. Rulers were called ahaw or “lord.”

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1188

Maya Stone Hacha

AD 800 – 1000

Early Postclassic South Coast of Guatemala

Elite members of society played a ritual ball game using a rubber ball on a walled court. Hachas, such as this one in the form of a man wearing a macaw mask, either were portable ball court markers or were worn on wood and leather protective belts in ceremonies after the game. This hacha was made by the Pipil, Mexican intruders into the Maya area, but similar examples have been found at Maya sites.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM4630

Maya Greenstone Bead

The bottom of a jade pendant has been sawed off and turned into a long bead. The pendant originally was carved with the figure of a ruler sitting cross-legged.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM4626

Maya Greenstone Earflare

AD 250 – 900

Earflares were the central part of elaborate ear ornaments worn by the Maya elite. Counterweights in the form of beads and hollow tubes were strung through the center of each earflare to hold it in place.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM174

Maya Cylinder Vase

AD 250 – 900

Classic Nebaj

Two vertical columns of glyphs divide the vase into two almost identical panels. In each panel a seated ruler under a draped ceremonial banner gestures to a standing figure. The seated person wears a headdress with a water lily extension and has a pillow wrapped in jaguar skin at his back. The lower-ranking figure stands at attention with crossed arms. Speech scrolls emanate from the mouths of each person, showing they are in conversation.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM1193