Maine’s Threatened Shell Middens: Losing a Link to Understanding Our Past

Alice Kelly

School of Earth and Climate Sciences

Climate Change Institute Department of Anthropology

Shell middens are cultural accumulations of shells, and occur worldwide wherever coastal residents deposit the remains of shells in a central location. Approximately 2,000 of these features are located along Maine’s mainland and land coasts. Most shell middens, or shell heaps, were created by Maine’s first residents, the Wabanaki, before the arrival of European colonists, and range in age from 4,000 years old through the time of European contact.

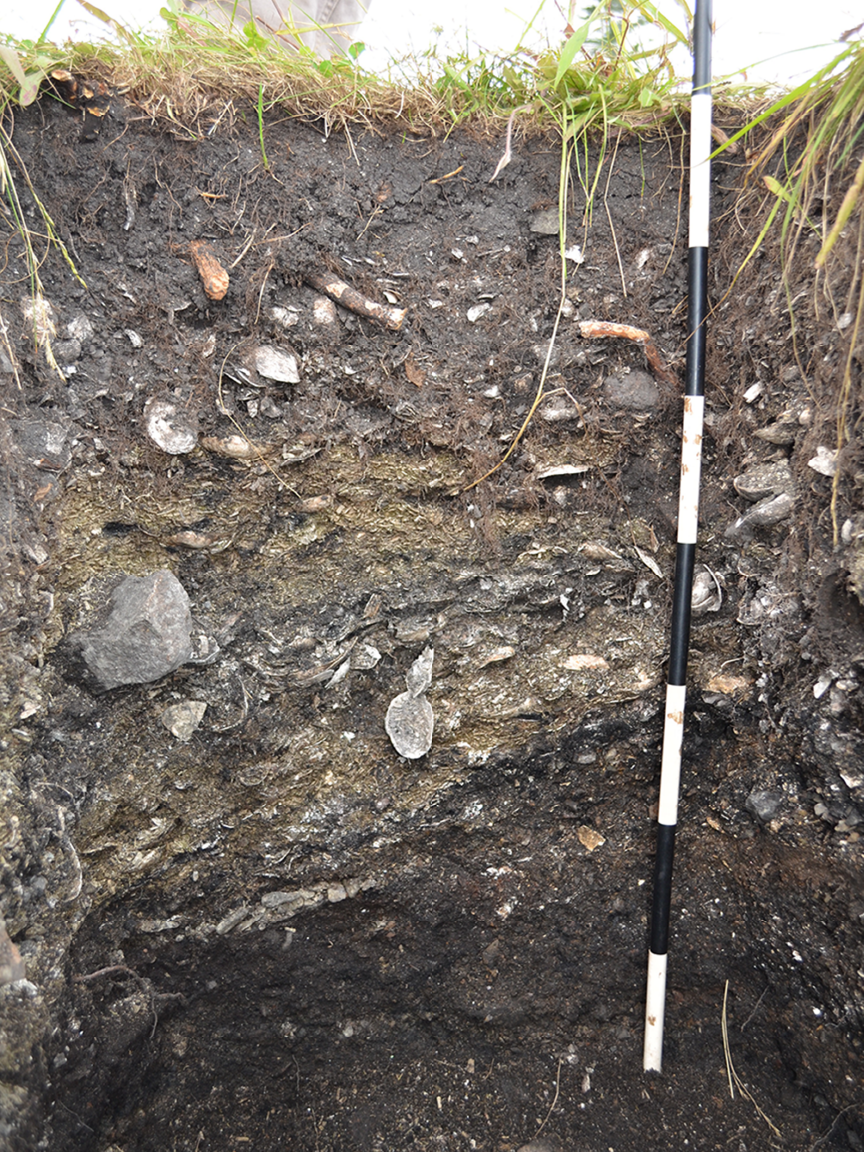

Maine’s shell middens are largely composed of clamshells. However, some of the middens in the Damariscotta area contain primarily oyster shells. Other cultural items, such as tools, ceramics and food remains, are often associated with shell middens. Careful excavation of shell middens that record the site stratigraphy (layering) and the exact location of artifacts within the midden to help archaeologists to determine the lifeways of these coastal residents, as well as understanding changing environmental conditions.

Visit the Maine Midden Minders website or download a PDF brochur

MIDDENS THIS WAY!

Shell middens have been a source of interest and speculation since the 1800’s. Once thought to be the remains of a mysterious ancient people and then simply as “Indian Trash Heaps,” we now know shell middens are rich archive of a cultural and paleoenvironmental information.

Image by Gabriel Hyrnick

Most Maine middens are made up of layers of soft shelled clam shells, either in layers of whole, single shells, or broken shells mixed with varying amounts of soil and organic matter. The breakdown of carbonate-rich mollusk shells buffers Maine’s acidic soils. As a result, middens preserve organic material that is lost at other archaeological sites. This material, in the form of bone tools and food remains, can help decipher the lives of indigenous costal people…subsistence strategies, tool production,seasonal movements, and interactions with their environment.

Image by Gabriel Hyrnick

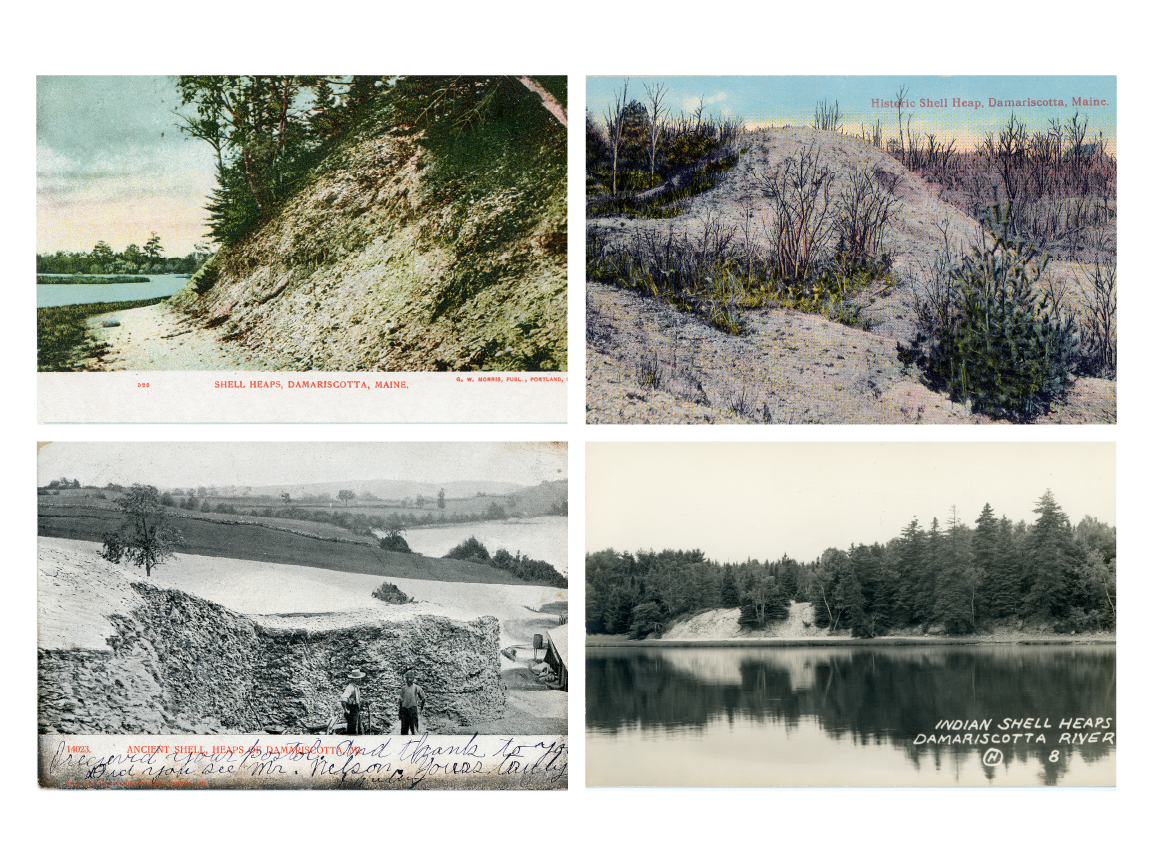

The well-known Glidden Midden and Wheleback Middens in the Damariscotta area are unusual in that they are located on a tidal river, not the coast, and are made up of over 19m (approx 15′) thick layers of oyster shells.

Image by Alice Kelly

The large Glidden Midden is part of a group of oyster shell middens on the Damariscotta River. The midden is over 10m high and extends over 100m long along the river bank. This site is now preserved by the Coastal Rivers Conservation Trust.

Image by Donald Soctomah

The impressive size of the Glidden Midden and the even larger Whaleback Midden caught public interest and economic attention in the 19th century. These historic postcards record the “wish you were here” wonder at the size and “mystery” of the middens, and the almost total destruction of the Whaleback Midden in the 1880’s by mining for lime and chicken feed. The remnants of the Whaleback Midden can be visited at the Whaleback State Historic Site in Damariscotta.

Hudson Museum Images

Current archaeological practice has changes since the early days of shoveling for artifacts. Careful investigations provide clues to past coastal life ways. when excavation provides important information, it also destroys the site. Archaeologists take samples and make detailed maps, measurements, photographs, and drawings so no information is lost.

Image by Alice Kelly

As excavation progresses, the location of artifact, such as stone or bone tools and pieces of ceramics, are carefully photographed and mapped before removal. Detailed documentation means the site can be “recreated” on paper or virtually. The white arrows in this photograph indicate scrapers, a small flaked stone tool used. to work hides or wood.

Image by Steven Cox

Archaeological excavation is time-consuming and hard, physical work. Layers of sediment and shells are uncovered in 5-10 cm layers. Each layer is drawn, photographed, and described. Artifact locations are plotted. Artifacts are collected and labeled for analysis.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Level by level excavation takes time, and sometimes tedious, but reveals important details. Here a 1m x 0.5m excavation unit has uncovered the edge of an approximately 1000 year old gravel-lined house floor at the edge of a midden.

Image by Gabriel Hyrnick

The archaeological record is not only told by artifacts. Varying layers of midden material can indicate differing activity areas. Rocks may indicate structures of hearths. The lower excavation unit in this image revealed post molds, or the remains of stakes driven into the base of the midden. Their function is unknown, and may represent overlapping periods of use.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

This detailed excavation reveals the interior dividing wall of a house and a hearth. Exposed excavation unit sides provides a continuous view of the site stratigraphy. Without this painstaking work, a large part of the archaeological record would be lost.

Image by Steven Cox

Screening, or sieving loose material from excavation units, is an important part of shell midden archaeology. This practice ensures that even small pieces of stone, bone, plant material, charcoal, or ceramics are recovered.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

After recovery from an excavation unit or a screen, material is washed, dried, identified, and catalogued. While not as eye-catching as projectile points and large ceramic pots, this material is critical in understanding how indigenous families lived in their coastal environment.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Soft-shell clam shells or oyster shells make up most of Maine shell middens, but other mollusks, such as mussels and razor clams, are also found in middens. These quahogs were recovered from the base of a shell midden in southern Maine.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Maine shell middens also contain faunal (animal) remains, of the birds, animals, and fish that indigenous people relied upon for food, tools, and shelter. Archaeologists use these bones to understand hunting and fishing strategies and the season of site occupation. The sturgeon bone on the left may represent spring or summer fishing. The beaver bone on the right represents an animal that may have provided food and a thick, warm pelt.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Clams have been on the menu for Maine residents for thousands of years. Here a modern fan of clams investigates the remains of a thousand year old clam dinner…or breakfast…or lunch.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Stone tools, such as this projectile point (approx. 3000 years old), are sometimes recovered from middens along with pieces of pottery. Artifacts like these created a long interested in “collecting” at middens.

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Collecting, known to archaeologists as “looting,” is all about artifacts and not about knowledge. Collectors frequently trespass on private property to dig for arrowheads to keep, trade, or sell. Once thought to be good fun, we now know that this type of disturbance detroys the site and all the information that it once had.

Image by Kerry Hardy

This illegal looters pit on conservation land on a Maine island mimics an archaeologist’s square, straight-sided excavation.

However, the site has been robbed of any information it can provide, and will experience faster erosion due to this activity.

Image by Alice Kelley

Middens face an even larger threat than mining and looting. Rapidly rising sea levels, combined with increasing freeze/thaw cycles, are threatening these important archives of the past. Shell middens on coastal bluffs adjacent to clam flats provided an ideal camping site for the indigenous hunting/gathering/fishing lifestyle. Now these sites are eroding as waves undercut the bluffs and sites collapse.

Virtually all of Maine’s shell middens are eroding. Coastal erosion associated with sea level rise has destroyed all but a few sites older than 4,000 years old. These shells cascading down the front of a beach-front bluff represent a thousand years or more of Maine cultural history.

Image by Alice Kelley

Sites originally close to the water are now removed by coastal erosion. As waves eat away at the sites, cultural and environmental information is lost to the sea. The orange flags in this image indicate bits of swordfish bones eroded from an approximately 4,000 year old shell midden. Cultural, environmental, and oceanographic information has vanished

Image by Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Even the iconic Glidden Midden, located on a relatively protected river bank, is experiencing erosion from tidal currents, ice, flooding, and boat wakes. What is to be done to save this valuable information in the face of inevitable sea level rise?

Image by Alice Kelley

Become involved! The Maine Midden Minders is a citizen science program designed to monitor and document shell midden erosion and archaeological information. Volunteers use simple tools to measure midden erosion and create a database for use by researchers and cultural resource managers.

Image by Alice Kelley

The Maine Archaeological Society provides a link between interested citizens and professional archaeologists. Annual meetings and volunteer opportunities are open to members. Open site days allow the public to interact with professional archaeologists and their students.

Image by Steve Bicknell

Reaching children is an important tool in changing a mindset. Here children visiting an excavation site are learning that artifacts are not the goal of an investigation, but the clues to understanding the ancient families who lived at these locations.

Image by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Shell middens are part of our shared cultural and environmental history and are special places to the region’s indigenous population. With approximately 2,000 shell middens on the Maine coast, we can not “save” them all. But, by recognizing their cultural, historic, and environmental value, we can document critical information and prevent human destruction.

Share your knowledge of Maine shell middens. Be a Midden Minder!

Image by Alice Kelley

Online Resources: