Wider Context

The West Mexican cultures did not exist within a vacuum. They were part of Mesoamerica, an area of intense cultural interaction covering all or parts of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. More than other parts of Mesoamerica, West Mexico may have been influenced by traders from cultures of the Pacific Coast of South America. People in West Mexico also felt themselves in contact with the supernatural world. Much more than simple reflections of everyday life, tomb figures are also religious icons which contain information about ancient concepts of the spirit world.

Archaeologists define Mesoamerica as a geographic area with shared basic cultural traits: agriculture based on maize, beans, and squash; Stone Age technology; society and economy organized around the agricultural village; leadership from a small elite class of kings and nobles; and fatalistic religion. As part of this area, West Mexico shared social institutions and belief systems with other cultures earlier and later in time. The ceremonial ball game played throughout Mesoamerica was clearly an important institution in West Mexico, and ball players are commonly represented among tomb figures. Symbols of rulership found in other areas, such as conch shells, seated position, and nose beads, appear in figures from elite shaft tombs.

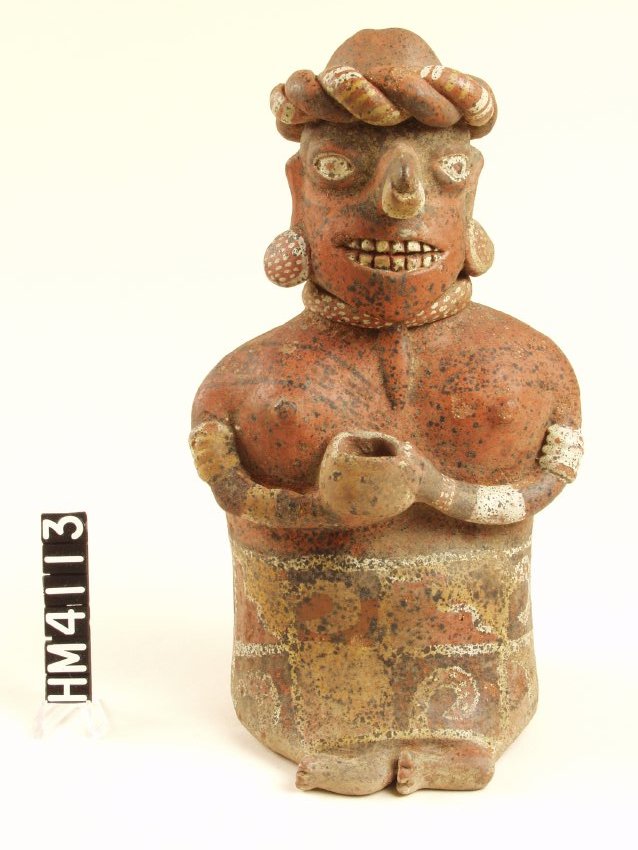

Colima Ceramic Figure

200 BC – AD 300

This figure has a conch shell trumpet on a strap.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM3677

Anthropologist Patricia Anawalt sees obvious connections between cultures of coastal South America and West Mexico. Clothing styles, fabric patterns, and personal adornments depicted on shaft-tomb figures are strikingly similar to ones represented on figures or found at archaeological sites along the northwestern coast of South America. Ecuadorian traders sailed great distances along the Pacific coast in search of supplies of Spondylus shells, which they provided to the elite of Peru’s powerful kingdoms. One source of the mollusk for them may have been off the coast of West Mexico. The presence of shaft tombs and similar dog and bird species in South America and West Mexico, but not elsewhere in Mesoamerica, supports the culture contact theory.

Views differ on the religious content of West Mexican shaft-tomb figures, from highly secular to very sacred. For decades many art historians believed that the art showed scenes of everyday life but nothing of the supernatural. In opposition, Peter Furst argues that many of the figures represent aspects of the spiritual: shamans who intercede with spirits, transformations, and non-ordinary reality induced by drugs. He interprets seated “horned” warriors turned to the left as shamans facing evil, rather than as rulers. Furst notes that many of the whistles found in tombs must have been meant for use in the supernatural realm, since a living person cannot physically blow them. In various figures, Furst sees spirits and gods similar to those in other parts of Mesoamerica, although other scholars continue to deny that any figures represent deities.

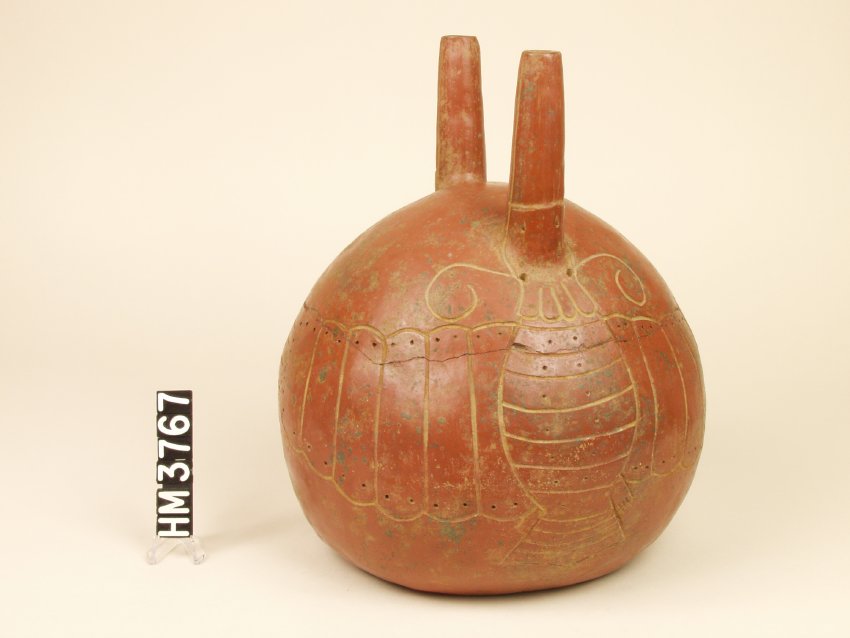

Colima Ceramic Vessel

200 BC – AD 300

This vessel depicts the wind god Ehecatl.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM3797