Original Context

Looters have found large hollow ceramic figures in West Mexican shaft tombs for more than a century. The hundreds of well-preserved figures, with their colorful surfaces and bold styling, have attracted collectors and museums around the world. Until recently, archaeologists did little work in the region. They had excavated very few unlooted tombs and could describe little of the figures’ original context, including when they were made. Now this is changing and archaeologists know most tomb figures date to between 200 B.C. and A.D. 300.

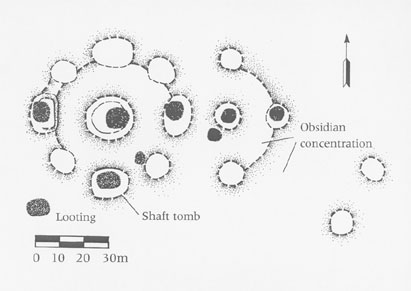

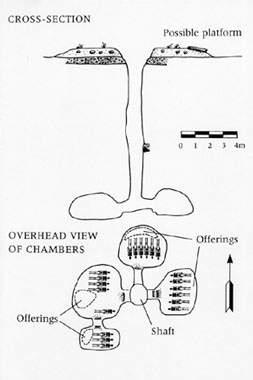

Mexican archaeologists Jorge Ramos and Lorenza López excavated an unlooted shaft tomb at Huitzilapa, Jalisco in 1993, recovering the complete contents of an elite burial. The tomb lay beneath a platform within a residential-ceremonial site and contained the skeletons of six members of a powerful chiefly lineage, four males and two females. From evidence on the bones, physical anthropologist Robert Pickering suggests that five individuals were closely related, and one female probably was related by marriage. Tomb contents included large Arenal style figures, food and liquid containers, decorated conch shells, jewelry of shell and precious stones, spindle whorls, spear-thrower parts, grinding stones, and the remains of fabric.

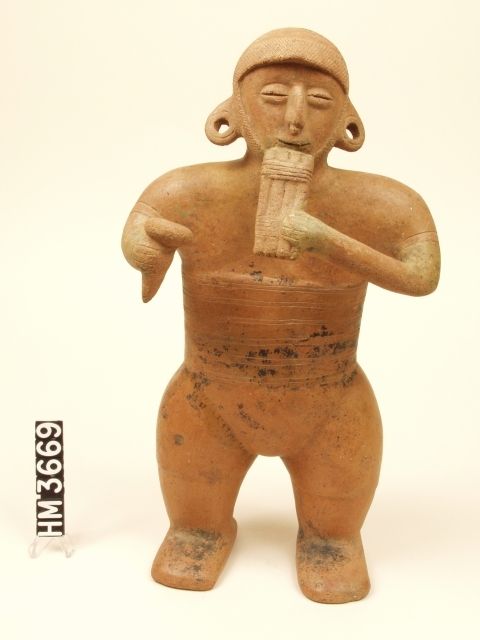

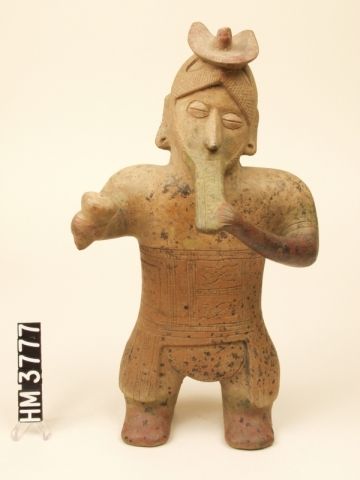

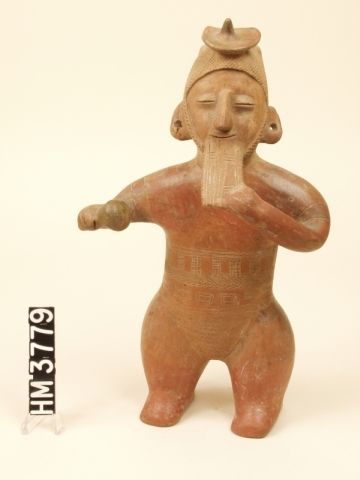

Colima Musician Figures

200 BC – AD 300

Comala Style

These six musicians came from the same tomb. Differences in technique indicate they were made by more than one craftsman. It is rarely possible to gather the contents of a tomb in one place again after the artifacts enter private collections.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM3669, HM3690, HM3713, HM3763, HM3777, HM3779

A variety of other objects besides large ceramic figures accompanied the dead in shaft tombs. Mourners placed the personal adornments of the deceased, such as necklaces and pendants made of precious materials, on and around bodies. The non-perishable parts of tools and weapons people used in life sometimes lie with the body. Reclinatorios apparently propped up the heads of bodies in some tombs. Quantities of bowls, plates, jars, and bottles contained food and drink offerings. Small solid figurines and whistles also come from tombs. Some objects placed with the dead show evidence of wear and had been used before burial, but most were made specifically to be placed around the mortal remains of tomb occupants.

Monumental shaft tombs are only a small subset of all graves in West Mexico, and represent the burials of people at the top level of society before A.D. 200. Most people were buried in simpler graves, often without large ceramic figures. Archaeologists have found small solid figurines, showing many of the same characteristics as large figures, in graves and trash middens.

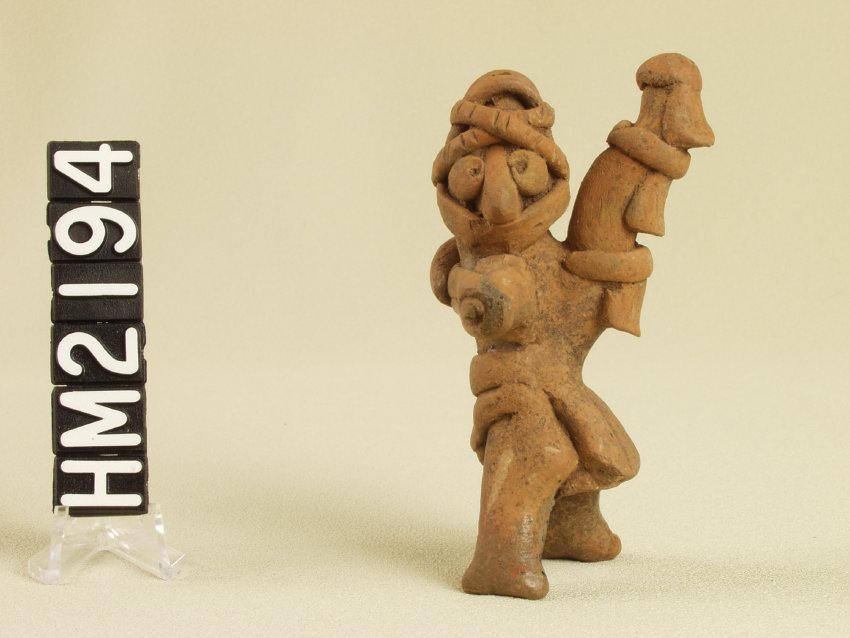

Jalisco Ceramic Figurine

200 BC – AD 500

The holes through each shoulder may indicate use as a pendant or ornament.

William P Palmer, III Collection

HM2260

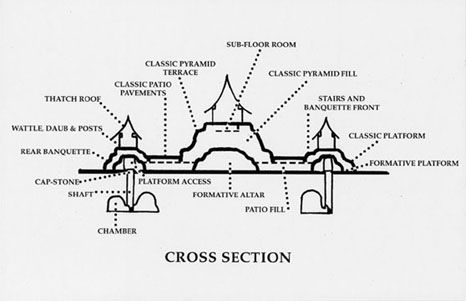

The rise of the Teuchitlán tradition in Jaliso after A.D. 200 marked changes in society. Construction of monumental surface architecture took the place of monumental shaft tombs, veneration of elite ancestors became less important, the layout of sites changed from cross-shaped to circular, social ranking gave way to stratification, and social positions became more important than who held them.

Illustration courtesy of Phil Weigand.

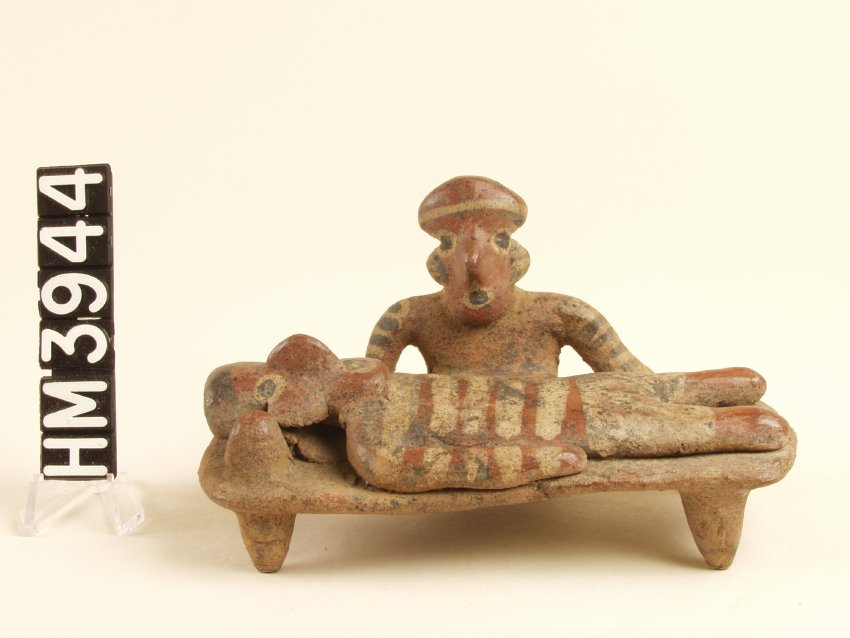

The energy spent in burying people shows that death was an important rite of passage in West Mexican society. It is clear that death was a time of mourning for those left behind. A common type of small solid figure has an attendant sitting beside a body tied to a bed. This may be an ill or dead person with a nurse or mourner. Larger figures of men and women are seated in mourning poses, with elbows propped on knees. Some have painted tears streaming down their cheeks. Part of the mourning ritual involved self-sacrifice. A mourner would pierce the cheeks with a sharpened bone or obsidian knife or make long cuts in the flesh of the arms, legs, and torso.