Novelties

“The idea of a design comes into the mind by itself and if you do not make it, you lose it, and it never comes back again.”

– Penobscot beadworker to Frank Speck in Symbolism in Penobscot Art (1927).

Beginning in the early 1700s, Native Peoples began to produce beaded moccasins and purses for sale to outsiders. These items, admired for their superb craftsmanship and exquisite beadwork, found a ready market among non-Natives. Beadworkers adapted traditional designs and borrowed new motifs and ideas, creating beaded forms that had no counterparts in their own culture. By the mid-nineteenth century, any imaginable fabric-covered household items could be ornamented with beadwork. Tea cozies, needlecases, watch pockets and ladies’ reticules were painstakingly beaded with tiny brilliantly colored seed beads. Each piece represented dozens of hours of work, in addition to the cost of materials – fabric and beads. Beadwork flourished among those who had ready access to materials and who received enough remuneration from their work to make their handiwork economically viable.

|

Maliseet Tea Cozy, c.1875Nancy & Roger Prince (NTP 14) |

Seneca-style Double Watch Pocket, c.1830With inscription : “James Percey Davey from his esteemed friend Wm Barry Ph…” Nancy & Roger Prince (NTP 21) |

|

|

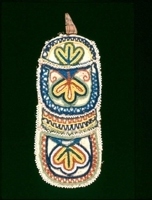

Mi’kmaq or Maliseet-style Purse, c.1875Nancy & Roger Prince (NTP 18) |

| Maliseet-style Domed Cap, c.1850-1870 This cap is composed of six triangular-shaped panels.Maine State Museum (96.16.1) |

|

|

Maliseet Tree-of-Life Motif Box, c.1840Nancy & Roger Prince (NTP 16) |

Seneca-style envelope needle case, c.1860Needle cases were an essential part of the Victorian woman’s sewing kit. Nancy & Roger Prince (NTP 23) |

|