New Spruce Budworm Testing Lab at UMaine critical to mitigating impact of destructive insect

A new testing lab at the University of Maine will help state landowners monitor their trees for the presence of the destructive eastern spruce budworm, a key step in tracking and mitigating a developing outbreak that could have severe impacts on Maine’s forest land and economy.

Angela Mech, UMaine assistant professor of forest entomology, heads the lab, where a research team led by lab manager James Stewart will test branches collected from sites across Maine for the presence of spruce budworm larvae. The levels of larvae present in each sample provide a window into the insect’s population in a given area that can inform management strategies and help landowners respond quickly.

Spruce budworm is a native insect that causes major damage to Maine’s spruce-fir forests on a regular cycle. While its endemic population is low, every 30–60 years the insect emerges in epidemic proportions that can devastate spruce-fir stands through defoliation. Maine’s last outbreak, during the 1970s–80s, killed millions of acres of trees, cost the state’s economy hundreds of millions of dollars, and had long-lasting effects on Maine’s forestry practices.

Since that outbreak, much has changed, but the spruce budworm’s potential to cause widespread forest destruction remains a serious threat, and a spruce budworm outbreak in the Canadian province of Quebec that started in 2006 has now reached Maine. Currently, more than 24 million acres of forest have been harmed by the ongoing spruce budworm outbreak in Canada.

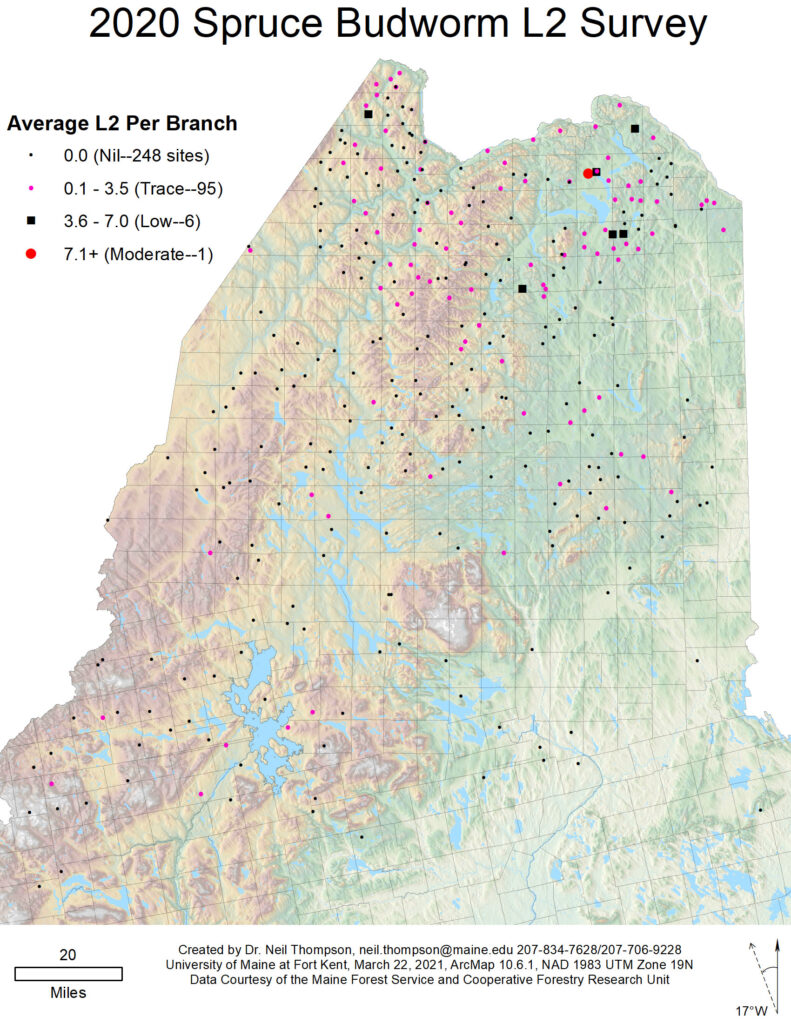

“This year, the red tinge of defoliation has been visible in hotspots throughout the St. John Valley for the first time since the 1980s,” says Neil Thompson, forestry professor at the University of Maine at Fort Kent and program leader at the Cooperative Forestry Research Unit (CFRU). “We have data from the Canadian Forest Service that indicate large flights of moths from Quebec reached northern Maine on July 15 and 20, 2019. Maine Forest Service pheromone traps and monitoring sites coordinated by the CFRU both identified increases where those flights were expected to land. This isn’t at the proportions of a major outbreak yet, but it’s a serious concern.”

Since 2013, when the Spruce Budworm Task Force was convened, Maine has been preparing to confront the next outbreak. A joint effort of the Maine Forest Service, Maine Forest Products Council, and University of Maine’s CFRU, along with leading spruce budworm experts, the task force released a risk assessment report in 2016 that offered detailed preparation and response recommendations for Maine’s forestry community.

“Although Maine’s forest is much different than it was during the last spruce budworm outbreak, there are still a significant number of acres that are currently at risk,” says Aaron Weiskittel, director of University of Maine’s Center for Research on Sustainable Forests. “We have several ongoing research initiatives at UMaine to prepare for and address spruce budworm, yet when and where it arrives is highly uncertain. This highlights the importance of a strong monitoring program.”

Increased monitoring was chief among the Spruce Budworm Task Force recommendations, and UMaine’s Spruce Budworm Testing Lab helps fill that need for Maine landowners, who previously did not have an in-state option for sample testing.

“Maine has been sending their samples to processing labs in New Brunswick,” says Mech. “That was a good solution when we were just keeping tabs on the situation, but now that the outbreak is here, landowners need a rapid response to help them uncover how much area is affected and what kind of management strategies they might want to explore.”

The process that Mech’s lab uses to test branch samples for spruce budworm at the second larval stage is central to an early intervention strategy that has been used in New Brunswick since 2014. Understanding how spruce budworms are growing and spreading allows forest managers to intervene sooner by adapting harvest activities to reduce the area available in high-risk stands of trees and consider targeted application of insecticide to protect foliage in small, infested areas that are not ready for harvest. Sampling and testing in the fall and winter is essential to identifying spruce budworm larvae during their hibernation period before they emerge to begin feeding on foliage in the spring.

“It takes months to prepare for management, so if you don’t find out you have a problem until February or March, it may be too late,” says Mech. “That kind of delay could cost that landowner a year of defoliation. By identifying hot spots early, they can control just that little spot rather than letting it expand and having a lot more area to treat. So far, they’ve been able to use early intervention strategies to keep the spruce budworm population in New Brunswick at bay during the current epidemic, and this gives the opportunity for Maine landowners to do the same.”

When it comes to spruce budworm mitigation, knowledge is power, and early intervention could help Maine avoid the potential worst-case scenario projection of 12.7 million lost cords of wood over the duration of a 40-year outbreak at a cost of $794 million per year and nearly 1,200 total jobs lost in the forest sector, according to the 2016 Spruce Budworm Task Force Report. The services provided by UMaine’s Spruce Budworm Testing Lab are just one aspect of a monitoring strategy that also relies on widespread pheromone trapping to track the influx of spruce budworm moths into Maine each summer.

Mech and Thompson are the principal investigators on a Cooperative Forestry Research Unit grant that provides more than $400,000 in funding for spruce budworm monitoring in Maine over the next five years. UMaine’s Spruce Budworm Testing Lab is funded through that grant and will conduct the testing of 900 branch samples from 300 sites across Maine to provide a yearly snapshot of spruce budworm population densities across the majority of the state. The lab also will conduct fee-for-service testing ($150/site) for landowners who are not CFRU members. To submit a sample, landowners must register their information on the Spruce Budworm Testing Lab website and then mail or drop off their branch samples to the university. Detailed information on how to correctly collect branch samples, an important part of the process, is available on the lab website.

“A spruce budworm lab in Maine is a critically important resource supplying all forest landowners a needed capacity for rapid spruce budworm monitoring,” says Ian Prior, CFRU executive chair and forest inventory manager for the Seven Islands Land Company. “This lab will be an important tool for managing and mitigating any future spruce budworm outbreaks and the economic impacts that result. It will allow for effective monitoring of hotspots and provide critical data for management decisions.”

For more information UMaine’s Spruce Budworm Testing Lab, updates on the current outbreak, and background on spruce budworm in Maine:

- Website for the Spruce Budworm Testing Lab

- Spruce Budworm Task force website

- Spruce Budworm Task Force Facebook page

Contact: Ashley Forbes, ashley.forbes@maine.edu