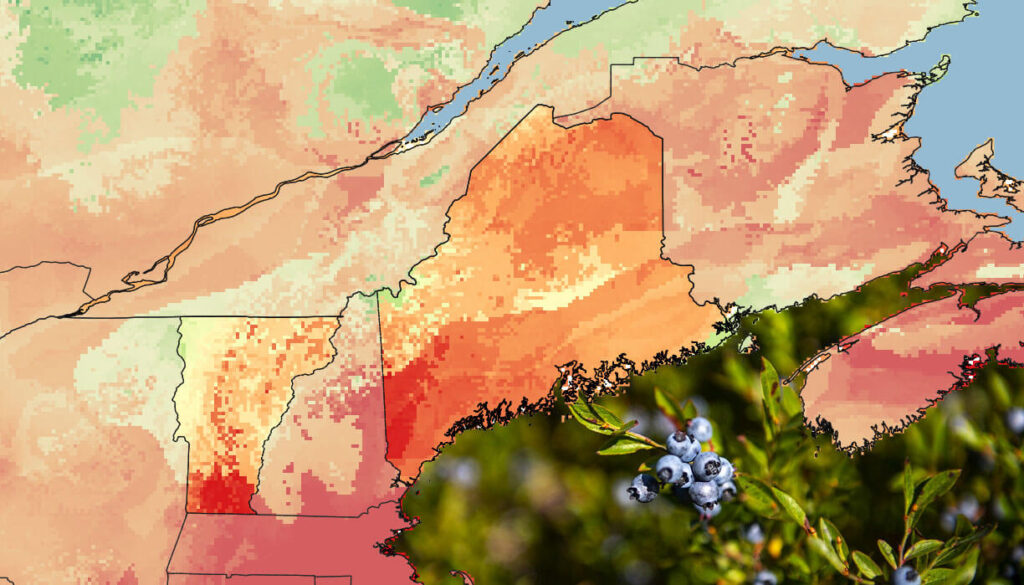

New data science project to model range shifts of hundreds of plant and animal species in New England

In response to a changing climate, populations of plants and animals move to more hospitable locations. Predicting where species will end up, and how New England farmers and rural communities need to plan and adapt accordingly is the focus of a new interdisciplinary research initiative led by the University of Maine.

The National Science Foundation awarded $4 million over four years to the EPSCoR Research Infrastructure project to develop novel approaches and software for modeling, visualizing and forecasting spatial and temporal data. The team — researchers from UMaine, University of Vermont, University of Maine at Augusta and Champlain College — will build some of the first mechanistic models of shifts in species ranges in response to climate change.

By harnessing diverse current and historical data with space and time dimensions, scientists will be able to better predict and help rural communities respond to the impact of climate change on biodiversity.

The goal is to better understand how plant and animal species — from forest plants and wildlife to diseases and their carriers, and agricultural crops — will respond to a changing climate in the next century. Data science and modeling will help inform farmers’ adaptation strategies, according to the research team.

The four-year initiative has multifaceted economic implications for Maine and Vermont, which are both EPSCoR (Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research) states. It will help create a trained workforce and strengthen research in the high-growth field of data science, provide insights to help conserve natural resources critical to livelihoods and cultural identity, and help farmers and other community stakeholders better prepare and manage their crops.

“Climate change is no longer an abstraction for farmers, foresters and others making their living off the land in Maine and Vermont. People are living the change. Scientists urgently need to move from warning about climate change to predicting the detailed nature of the changes we can expect and communicating this effectively to the people who need the information,” according to principal investigator Brian McGill, UMaine professor of biological sciences, who has a joint appointment in the Sen. George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions.

Co-principal investigators on the project are Nicholas Gotelli, the George H. Perkins Professor of Zoology, and Meredith Niles, assistant professor of food systems, both at the University of Vermont; Timothy Waring, UMaine associate professor of social-ecological systems modeling, who also is affiliated with the Mitchell Center; and Matthew Dube, assistant professor in computer information systems at the University of Maine at Augusta.

Other members of the research team are Laurent Hébert-Dufresne, UVM assistant professor of computer science; Laura Corlew, UMA associate professor of psychology; and Narine Hall, assistant professor and program director in data science at Champlain College.

Using historical data, Gotelli and McGill will lead development of a new model of how hundreds of species across geographic ranges in the United States will respond to climate change over time. The model seeks to better predict the transient dynamics of species’ range shifts, including the effects of human modification of landscapes, for each decade (2030–2120).

Hébert-Dufresne will extend these models to explore the effects of climate change on diseases. This will be the first Eastern U.S. analysis of species of animals, plants, crops and zoonotic diseases, such as Lyme, West Nile and Equine Encephalitis.

“This research brings together experts in biodiversity, disease dynamics, cultural evolution, agriculture and computer science. With this diversity of perspectives, we are excited to begin working together,” says Gotelli, who, like McGill, has collaborated extensively in the last 15 years on research related to community ecology and biodiversity response to global change.

Waring will lead development of cultural evolution models of rural community adaptation to climate change. He and his team will explore what social and economic conditions determine how a natural resources-based community adapts to climate-induced change over time, and whether cultural adaptation models coupled with data on species changes can better inform farming practices in the future.

Niles will develop a large-scale spatiotemporal dataset that will focus on and inform farmer adaptation behaviors. The data will include projected range shifts in crops, models of key crop weeds and pathogens, and socioeconomic and demographic information on the rural resource users.

Together, the work of Waring and Niles will be the first to leverage significant ecological and social datasets to study climate adaptation in a spatiotemporal context.

Dube, McGill and Hall aim to increase research capacity, by creating new software tools to make it easy for scientists to work with and analyze the high volumes of spatiotemporal data being generated.

The project also seeks to go beyond producing new research and tools for scientists by developing the communication systems and workforce development needed to effectively create, implement and advance them in the next 100 years.

Led by Corlew, the researchers will work closely with New England farmers to understand what data they need to plan and manage climate change-related shifts in crops that are potentially most viable on their land. The resulting complex data related to climate adaptation ultimately must be communicated effectively to stakeholders and the community. Led by Hall, outreach will include the creation of “tools that make it easy for nonprogrammer scientists to work with and merge diverse formats of spatiotemporal data,” note the researchers in their proposal.

The project has significant implications for workforce development in data science, an expanding job market in New England. In addition to building research capacity and expertise at the four higher education institutions, the project will provide curriculum and training in data science at the high school, undergraduate, graduate and faculty levels.

“This project will help to train the future data science workforce in Maine and Vermont, and will build capacity to utilize spatiotemporal data within the existing workforce,” according to the research team. “Our workforce development plans extend from high school students to senior faculty members. In addition, our outreach to the agricultural sector will help farmers make more informed decisions that impact their livelihoods, the character of rural communities and the quality of food that is available in Northern New England.”

Contact: Margaret Nagle, 207.581.3745