Helen Hartness Flanders

Helen Hartness Flanders 1890 – 1972

Helen Hartness was born in 1890, into a prominent Vermont family. Her father, James Hartnes, served as the Governor of Vermont from 1921 to 1923. In 1911 she married Ralph Flanders. They had three children.

Helen Hartness Flanders was one of eleven Vermont writers who formed the Committee on Traditions and Ideals within the Vermont Commission on Country Life. These writers were interested in rejuvenating some of Vermont’s 18th and 19th century history. In 1929 the Committee asked Flanders to collect traditional Vermont songs for a 1931 book Vermont Folksongs and Ballads.

Flanders began intensive collecting efforts in 1931, using a dictaphone to record singers. She sent out form letters and articles to nearly every newspaper in Vermont, asking for information on old ballads. She published A Garland of Green Mountain Song and Country Songs of Vermont based on these collections.

Nancy-Jean Seigel describes her grandmother’s relationship with the singers:

“She cared deeply about people and took them for who they were. Over time, her collecting activities led to warm friendships. The day she recorded Mr. Sparks at the Weston Old Home Day, they ended up sitting under a maple tree while he told her about his days as a sailor and showed her how to tie knots. . . . On some occasions she would return to a home with her recording machine so that family members could hear the voice of a relation who had passed away. Notes and small gifts passed back and forth between collector and singers. The ratty-looking bearskin rug beside my grandmother’s bed was a gift from Hanford Hayes from Maine. He had trapped the bear himself.”

Nancy-Jean Ballard Seigel. “Field Days in the Flanders Collection.” Folklife Center News, Vol. XXIII, no. 2 (Spring, 2001).

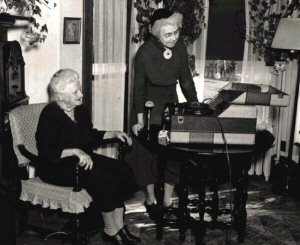

Helen Hartness Flanders records Mrs. Elwin Burditt, of Springfield, Vermont, probably around 1949. The reel-to-reel tape recorder on the table was the most advanced, most portable recording technology available to folksong collectors at that time.

A page from the first fruit of Flanders’ collecting, Vermont Folk-Songs and Ballads, 1931.

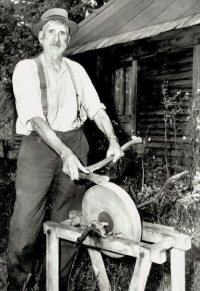

Helen Hartness Flanders knew that you can never tell who will know old songs. Sometimes people who look the least likely will have learned many songs from their relatives and friends. Which of these people do you think is the most likely to know folksongs?

|

|

|

|

In fact, all of them were recorded by Helen Hartness Flanders.

Flanders shared her songs with the public through a weekly newspaper articles published in a variety of New England newspapers in the early 1930s and again in the 1940s. She published in the Springfield Republican in Massachusetts, the Narragansett Times in Rhode Island, the Springfield Reporter in Vermont, the Waterbury Republican in Connecticut, and the Bangor Daily News, in Maine.

In 1939 Flanders met Marguerite Olney. Olney was a graduate of the Eastman School of Music, in Rochester, NY, and therefore could help Flanders with her area of greatest difficulty: music transcription and analysis. In 1941 Flanders donated her ballad collection to Middlebury College in Vermont, and Marguerite Olney was hired as the collection’s curator. Flanders also donated most of the money for Olney’s salary, as well as to buy gas and tapes for collecting trips. Flanders continued to provide the primary financial support for the collection until 1958. Marguerite Olney was as much a collector as a curator for the collection. Throughout the 1940s and most of the 1950s, Olney spent her summers traveling throughout New England. These efforts resulted in their collaborative book, Ballads Migrant in New England in 1953.

Helen Flanders describes the excitement of collecting:

“Each collector who recovers and preserves this material has his own especial associations. The Vermont Archive contains some nine hundred and twenty-one texts and four hundred and five records of tunes. The intangible, indescribable delights which went with the collecting of each song are not filed with them. These cannot exist in words. The glow or the gloom with which one day ends and another is anticipated remains unstated. The warmth of heart where in some home a common appreciation of certain lines in their tunes falls alike upon a collector and singer cannot be itemized and classified as Early American or British.

Even that moment before driving out of the yard, with the dictaphone, address books, looseleaf notebooks, etc., on the seat of the car, cannot be distilled into the written word. Just beyond the windshield is the day-which one regards as untouched and undoubtedly undeserved (in the flurry of what is to be neglected at home)-so different each time, but always so electric with the unknown.”

Helen Hartness Flanders, “The Quest for Vermont Ballads,” Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, NS 7, no. 2 (June 1939), p. 53-72.

From the 1930s through the early 1960s Flanders gave to historical societies, women’s groups, folklore organizations, poetry meetings, Women’s Clubs, college campuses, etc. These lectures were short talks that included a request for further folk songs. She would often bring one of her informants with her to sing their traditional songs.

“Once at a large New England college the singer was giving what he had learned in lumber camps; he had with him, as well, his fiddle for such tunes as had no words. He was “going strong.” Whatever he chose to sing was most enthusiastically applauded. He became more and more at home with the people before him. One song reminded him of another; each song was less proper for public performance. All present were held in a bond of fascination. Faces became enigmatical or aghast or animated with humor as the verses took their own natural medieval course, while the singer regarded each song as just another ballad. The tension was fairly paralyzing. Where would he stop? Would he stop of his own accord, or was he entirely out of hand? When he started the next song, a real emergency was indicated, for which there had been no rehearsal. The fiddle might prove the antidote. The speaker touched him on the sleeve, saying, ‘There are but a few minutes left for them to hear you play.’ With a startled look, he picked up his fiddle. The audience seemed to exhale.”

Helen Hartness Flanders, “The Quest for Vermont Ballads,”

Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, NS 7, no. 2 (June 1939), p. 53-72.

Between 1960 and 1965 Flanders published a four-volume work of Child ballads, Ancient Ballads Traditionally Sung in New England. After her death in 1972, the Archive of Folk Song at the Library of Congress recognized the importance of Flanders collections, and made copies of the Flanders sound recordings for their permanent collection.

Nancy-Jean Ballard Siegel is currently working on a biography of her grandmother, Helen Hartness Flanders. She is particularly interested in contacting people who sang for Flanders. If you are one of these people, or know someone who was recorded by Flanders, please contact Nancy-Jean Siegel at:

Nancy-Jean Siegel4936 Sentinel Drive, Apt. 404

Bethesda, MD, 20816