Bulletin #4427, Cycles of Development

Judith Graham Ph.D., Extension human development specialist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Developmental Cycles

- Becoming—From Conception to Birth

- Stage 1—Being: Birth to Six Months

- Stage 2—Doing and Exploring: Six to Eighteen Months

- Stage 3—Thinking: Eighteen Months to Three Years

- Stage 4—Identity and Power: Three to Six Years

- Stage 5—Skills and Structure: Six to Twelve Years

- Stage 6—Integration and Regeneration: Twelve to Nineteen Years

- Stage 7—Recycling: Adulthood

- Stage 8—Toward Death: Integration of Life Experiences

- Change Points—“Spirals Within Spirals”

- Using Developmental Cycles in Adult Education

The last edition of Family Issues presented a relational perspective of how we develop as humans, as put forward by the women and men associated with the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute and the Stone Center at Wellesley College.

This edition introduces another perspective—that of human development through the lens of Transactional Analysis (TA). Transactional Analysis is a theory of interpersonal communication, development, growth and change. TA is based on mutual respect, acceptance and the belief that everyone has the ability to learn and the potential to change.

Eric Berne popularized his original ideas with the international best seller, Games People Play (1964). Thomas Harris expanded TA’s influence with I’m OK, You’re OK in 1973. I first studied TA in an early graduate course as a framework for counseling. Since then the educational and organizational applications of TA have significantly expanded worldwide, creating separate but equal fields of TA. It is now widely used in education, organizations, training and personal development, as well as in the original applications of psychotherapy and counseling.

This Family Issues introduces the powerful TA concept known as Cycles of Development. Pam Levin won the prestigious Eric Berne Memorial Award for this contribution to TA theory in 1984. Other TA scholars and practitioners have extended the application of Levin’s original ideas: Jean Illsley Clarke in parent education, Julie Hay in organizations, and Rosemary Napper and Trudi Newton in education. The writings and teachings of these brilliant women form this issue of our newsletter.1

The idea of growth as a cycle is common to many cultures and religions including the Native American medicine wheel circle, ancient Egyptian and Persian doctrines, Taoism and Buddhism. What these perspectives have in common is a cycle based on nature—a rhythmic circle of seasonal growth and return. Berne recognized that developmental processes begun in childhood remain active and important throughout our lives, challenging the modern, technological perspective that presents development as linear.2 T. S. Eliot perhaps states this perspective most eloquently: we “arrive back at where we started, and know the place for the first time.”3

1 Clarke won the Eric Berne Memorial Award in 1995 for her outstanding application of TA theory to parent education.

2 Levin’s model also reflects Erickson’s ideas on the cyclical nature of development. Eric Erickson was Berne’s teacher and therapist; Berne was Levin’s teacher.

3 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 136-137. Eliot, T. S. (1942). Little Gidding.

Developmental Cycles

As we move through life from birth to death, we respond to an internal developmental clock or organizational pattern that prescribes the tasks and skills we need to learn. Pam Levin describes these shared patterns of growth as part of the “primitive forms we carry deep in our ancestral memory.”1 Jean Illsley Clarke describes these developmental stages as “describable segments in growing up.” The overarching task in each stage is to find or create an age-appropriate answer to each of four questions: Who am I? Who are you? Who am I in relation to others? How do I get what I need?2

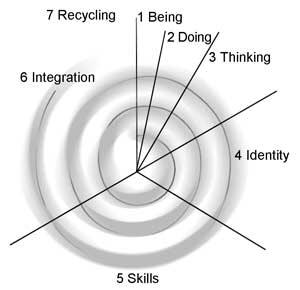

The pattern Levin describes has seven developmental stages. The first five stages cover the time period from birth to about age 12. These stages are Being, Doing, Thinking, Identity and Skills. At about age 13 we enter Stage 6, which is a recycling stage called Integration.3 This stage lasts until we are about 19 years old; it is a repeat of the first five stages but at twice the pace. The seventh stage—formally named Recycling—covers all our adult years. Over the course of adulthood, we return to the themes and issues of the earlier stages with new opportunities to “grow through” the developmental issues each stage represents. We either encounter or can create opportunities to revisit each stage as many times as we need to.

Clarke and Dawson made two changes to Levin’s stages. Levin incorporated both the prenatal and first six months into Stage 1. Clarke delineated these into two separate stages, naming the prenatal months “Becoming.” Clarke also added an end-of-life stage—Stage 8: Toward Death—for the developmental tasks of the last phase of our lives.4 Julie Hay added the ideas of “spirals within spirals” to more accurately reflect the complexity of how developmental tasks and cycles are layered in real life.5

One way to think about these ideas is to visualize a tree. A rare few of us are able to get all that we need in each of the first six developmental stages so that we grow straight and tall. Most of us don’t grow up that way, however. When we don’t get what we need at each stage, or we aren’t able to accomplish the stage-appropriate developmental tasks, we end up with holes or knots or bends in our core or “trunk.” These gaps or twists may occur at one or more stages. The adult recycling of Stage Seven provides opportunities to repair the holes, fill in the gaps, unravel the knots, and unbend what isn’t “true.”

Eric Berne gave us another metaphor for growth. Picture a stack of pennies. Each penny represents a developmental task, starting with Stage 1 on the bottom and adding additional pennies for each of the tasks and stages in turn. When all the pennies are flush and even, the foundation of the stack is firm. You can add any number of pennies and they won’t topple over. If, however, one or more of the pennies that form the base of the stack is slightly bent, curved or irregular, then the stack becomes skewed or starts to zigzag. All the pennies stacked on top of the uneven one are less secure regardless of how “true” or even they are. The uneven pennies change the direction and balance of the stack. Recycling offers opportunities to make the bent pennies true and to redirect and rebalance our developmental “stacks.”6

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 129-139.

2 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden, 211.

3 Levin originally named this stage Regeneration. Julie Hay renamed it Integration; Napper and Newton also use the name Integration, as will we. To add a bit more confusion to this, in Growing Up Again, Clarke labeled her new Stage 8 “Integration.” In this publication we have used only her subtitle, “Toward Death,” for this stage. There is evidence that recycling occurs in earlier stages, particularly Stage 5 – Skills (age 6–12). Stage 6 differs in that recycling is the primary focus. Clarke, J. I. (2003) Personal correspondence.

4 Clarke & Dawson. 218-220, 240-242.

5 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 206-208.

6 Berne, E. (1961). Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Grove Press, Inc. Reprinted 1975, London: Souvenir Press Ltd., 52-53.

Interested in learning more about TA? See Julie Hay’s Working It Out at Work – Understanding Attitudes and Building Relationships (Sherwood Publishing; Rosemary Napper and Trudi Newton’s Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors (TA Resources); Jean Illsley Clarke’s Self-Esteem: A Family Affair or Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children (Hazelden); or Ian Stewart’s and Vann Joines’ TA Today: A New Introduction to Transactional Analysis (Lifespace Publishing).

Becoming—From Conception to Birth1

Description: The prenatal stage lays the groundwork for all the stages to follow. During these nine months, if all goes well, the baby’s body is developing from the genetic gift of the egg and the sperm to a full-term infant with all life-supporting systems intact or ready to grow to full potential. Simultaneously, the new being is making life-shaping decisions in response to the environment of the womb and the relationship experiences of the mother with other people and with the baby.

Main question to be addressed: Is it safe for me to develop fully and be born?

Developmental Tasks:

- To grow; to develop all body systems.

- To accept nourishment, acceptance, reassurance and love.

- To gain familiarity with the mother.

- To make some deep decisions about trust.

- To initiate and move through the birth process.

Recycling: When we revisit Becoming, we may feel more than we think, we may need time to “gestate,” to gather up our feelings and thoughts, and to be cared for and respected for what we are doing even though we may not be able to articulate it well. We may resort to being hurried.2

After birth, Becoming is significant2

- When pregnant.

- When we know we are going to experience a great change, especially one imposed from outside, without sufficient information to feel confident of ourselves.

Clues for returning to Becoming:

- Feeling an unaccounted-for incompleteness.

- Lack of joyfulness not otherwise accounted for.

- Stuck, not able to get started and without words to describe that feeling.

- Any addiction or compulsive behavior.

- Believing you have to do everything yourself; trying to start things and not finishing.

- Self-destructive behaviors, recklessness, extreme risk taking.

- Strong and intense reactions to minor disappointments.

- Irrational fears or chronic anxiety not otherwise accounted for.

- Chronic depression; thoughts of suicide.

Affirmations for all ages:

- You can make healthy decisions about your experiences.

- Your life is your own.

- Your needs and safety are important.

1 Jean Illsley Clarke added this stage to Levin’s original developmental theory; it precedes Levin’s Stage 1 (Being. Excerpted from Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 218-220. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

2 Clarke, J. I. (2003). Personal correspondence.

Stage 1—Being: Birth to Six Months

Description: This first stage is about the experience of just being in the world. Our acceptance is not based on anything we do, simply on being who we are. Being requires environments that are trustworthy and safe, places where our basic needs for survival and recognition are consistently and lovingly met. We need to experience being secure, wanted and loved. Stage 1 is a time to gather strength, to build energy in order to reach the capacity to move into action. It is a time to take in.1, 2

Main questions to be addressed: Is it okay for me to be here, to make my needs known and to be cared for?3

Developmental Tasks of the Child:3

- To cry or otherwise signal to get needs met.

- To accept touch and nurture.

- To bond emotionally, to learn to trust caring adults and self. To decide to live, to be.

Compromise: If we don’t get enough of what we need in this first stage, we may have difficulties focused on our right to exist.2, 4

Recycling: When we reenter Being, we may stop doing things, stop thinking and simply exist. We may want to eat more frequently and sleep more. We may have difficulty concentrating; we seek recognition for simply being who we are and not for what we do. We may have heightened needs for touching and being touched and for renewing or developing close relationships with others.1

Clues for returning to Being:1, 3

- Feeling we have “run out of gas” emotionally.

- Questioning our adequacy, feeling helpless, and questioning whether others can be trusted.

- Wanting others to know what we need without our asking; not knowing what we need; not needing anything; feeling numb.

- Believing others’ needs are more important.

- Not wanting to be touched, or compulsive touching, or joyless sexual touching.

- Unwillingness to disclose information about ourselves, especially negative information.

After six months, Stage 1 is significant 1

- When we are tired, hurt, vulnerable, ill or under stress;

- During periods of rapid change or growth;

- When suffering a personal loss;

- When taking care of an infant or when pregnant; and

- In the beginning of a new process (i.e., a new job or relationship).

Affirmations for all ages:3

- I’m glad you’re alive.

- You belong here.

- What you need is important.

- You can feel all your feelings.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 130-131.

2 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.3-2.4.

3 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 221-222. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

4 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 205.

Stage 2—Doing and Exploring: Six to Eighteen Months

Description: The second stage is characterized by intense interest in and curiosity about our surroundings. We want to move and explore, to touch and taste and see everything. Our world rapidly expands and we can’t seem to get enough of it. This is a time of finding our footing and getting our feet on the ground in a different way. During this phase we learn about trust, and the extent to which we can trust others, our environments, our senses and what we know. We are deciding if we can be creative and active and get support for doing all these things. We need caregivers who are both consistently available when we need security and reassurance, and who allow us plenty of safe spaces for free exploration. We need to decide that it’s okay for us to move out into the world, to explore, to feed our senses and still receive support.1,2, 3, 5

Main questions to be addressed: Is it safe for me to explore and try new things and to trust what I learn?3

Developmental Tasks of the Child:3

- To explore and experience the environment; to develop initiative.

- To develop sensory awareness by using all senses.

- To signal needs; to trust others and ourselves; to get help in time of distress.

- To continue forming secure attachments with parents, caregivers and others who play a significant role in the child’s life.

- To start to learn that there are options and not all problems are easily solved.

Compromise: If we are thwarted in our explorations during this stage by inconsistent care giving or overprotection, we may become perpetual explorers or we may be reluctant to enter into new situations.2, 4

Recycling: When we reenter Doing, we may have a short attention span and have difficulty setting goals. Our need to be mobile and active becomes paramount. As in our first experience of this stage, our curiosity is heightened as well as our intuitiveness. We may recycle this stage by frequently changing homes, jobs and cars and by choosing action or adventure-type activities for leisure or vacation time. Or we may be scared to do any of these. We may not care about finishing tasks. 1, 2, 6

Clues for returning to Doing:1, 3

- “Doing” issues become prominent.

- Not knowing when to initiate and when to be inactive; reluctance to initiate.

- Conflicts about whether to be goal-directed or not have any goals for a while.

- Boredom; seeking or developing new motivations in life.

- Avoiding doing things unless you can do them perfectly.

- Not knowing what you know.

- Thinking it is okay not to be safe, supported, protected.

- Trouble finishing tasks.

After eighteen months, Stage 2 is significant 1

- After being nurtured for awhile;

- In any new physical setting;

- As part of the creative process;

- As a prelude to establishing a new level of independence; and

- When taking care of a toddler.

Affirmations for all ages:1

- You can know what you know.

- You can do things as many times as you need to.

- You can be interested in everything.

- You can use all your senses when you explore.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 131-132.

2 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.4.

3 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 223-225. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

4 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 205.

5 Julie Hay uses the term “Exploring” for this stage – a term that accurately describes the major developmental task during this time. Hay, J. (1995). Donkey Bridges for Developmental TA. Watford, Hertfordshire, UK: Sherwood Publishing.

6Hay, J.(2003) Personal correspondence.

Stage 3—Thinking: Eighteen Months to Three Years

Description: We begin to establish a new sense of independence, individuality and separateness in Stage 3. We start to reason things out, think for ourselves and solve our own problems. We want to make room for ourselves apart from others; what’s “mine” is an important theme. This is a time of testing reality and pushing against limits in ourselves and those imposed by others. We may strongly object when others impose their decisions or ideas on us; concerns about the control we have over ourselves and situations are central. “No” and “I won’t” may be our favorite words. In addition to intense negativity, we may also express ambivalence as we learn whether to trust or distrust our knowing and thinking. We may invite others to think for us and then become furious when they do. We need to decide that it’s okay to push and test, to find the limits, to say “no,” and to become separate. Establishing that we are important is a major developmental task of this stage.1, 2

Main question to be addressed: Is it okay for me to learn to think for myself?3

Developmental Tasks of the Child:3, 5

- To establish the ability to think for oneself; to think and solve problems with cause-and-effect thinking.

- To test reality, to push against boundaries and other people.

- To start to follow simple safety commands.

- To express anger and other feelings.

- To separate from parents, caregivers, and other significant parent figures without losing their love.

- To start to give up beliefs about being the center of the universe.

Compromise: If we are not allowed to develop our thinking and problem solving skills, we may find it hard to form our own opinions or solve our own problems later in life. This distrust of our thinking is often expressed as “I don’t know.”2

Recycling: As in our first experience of this stage, our curiosity is heightened as well as our intuitiveness. We feel a need to establish a new level of independence and individuality—our separateness.1, 4

Clues for returning to Thinking:1, 2

- Feeling angry about everything in general; inappropriate rebelliousness (chip on shoulder).

- Fear of anger in self and others; indirect expressions of anger through behaviors.

- Wanting to establish what is “mine” and what is “yours.”

- Lots of questions about separateness, responsibility and thinking (especially resistance, contrariness, forgetfulness, discounting/accounting, stubbornness, procrastination and greed).

- Rather be right than successful.

- Think the world revolves around us.

- Scared to say yes or no without thinking.

After three years, Stage 3 is significant1

- When breaking out of a dependency relationship (with a lover, spouse, mentor, employer or friend);

- When learning new information;

- When developing a new personal position or taking a stand;

- When changing agreements; and

- When parenting a toddler.

Affirmations for all ages:3

- You can become separate from me and I will continue to love you.

- You can know what you need and ask for help.

- You can think and feel at the same time.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 132.

2 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.4-2.5.

3 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 225-227. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

4 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 205.

5 Hay, J. (2003). Personal correspondence.

Stage 4—Identity and Power: Three to Six Years

Description: This fourth stage is for discovering who we are. We explore many aspects of our identity and internal organization—gender, style, roles, clothes, props, social relationships and power. We test the consequences of our behavior and our capacity and ability to influence others. To do this, we may set up disagreements, start or repeat false rumors and have urges to lie or shoplift. This is also a time when the separation between fantasy and reality really begins. We need to decide that it is okay to have our own view of the world, to be who we are, and to test our power.1, 2

Main questions to be addressed: Is it okay for me to be who I am, with my unique abilities? Is it okay for me to find out who others are and learn the consequences of my behavior?3

Developmental Tasks of the Child:3

- To assert an identity separate from others.

- To acquire information about the world, self, body and sex role.

- To learn that behaviors have consequences.

- To discover our effect on others and our place in groups; to learn socially appropriate behavior.

- To learn to exert power to affect our relationships; to learn the extent of our personal power.

- To separate fantasy from reality.

Compromise: Without appropriate guidance and support at this stage, we may grow up to be unsure of our role in life, or with rigid views that limit our potential development. At this stage, we may unsuspectingly “decide” to live our life in line with some predetermined outcome, as if we were actors with a script or story that dictates the limits within which we may act. Because this script is unknowingly created, we will have no conscious recollection of it when we are older. Later in life, the loss of a job, retirement, an “empty nest” or the loss of a spouse or partner may trigger extreme uncertainty about who we are.2, 4, 5

Recycling: Returning to this identity stage brings up questions and issues related to power and gender: potency and impotency, magic, creating or destroying, hurting and healing. Adults recycling this stage may change their appearance, lifestyle or work.1, 2

Clues for returning to Identity:3

- Having to be in a position of power; being afraid of or reluctant to use power.

- Unsure of personal adequacy.

- Frequently comparing oneself to others and needing to come off better.

- Identity confusion—needing to define oneself by a job or a relationship.

- Feeling driven to achieve.

- Overuse of outlandish dress or behavior.

- Wanting or expecting magical solutions or effects.

After six years, Stage 4 is significant1

- After renegotiating a social contract;

- When carrying out a new role;

- When seeking a new relationship to family, job, or culture; and

- When caring for preschool children.

Affirmations for all ages:3

- You can try out different roles and ways of being powerful.

- You can be powerful and ask for help at the same time.

- You can explore who you are and find out who other people are.

- You can learn the results of your behavior.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 132-133.

2 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.5

3 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 228-230. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

4 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 205.

5 Hay, J. (2003). Personal correspondence.

Stage 5—Skills and Structure: Six to Twelve Years

Description: During the six years we initially spend in Stage 5—and any time we revisit it—we are acquiring the skills, tools and values we need to get by in the world. To install this internal framework, we incorporate a whole range of opinions and values in order to perceive the world in a structured, coherent way. This includes understanding the need for rules, the freedom that comes from having appropriate rules, and how rules help us get by in the world. One way we do this is to observe others’ behavior and copy whatever fits with the identity we have chosen. Another way is by arguing and hassling with others’ ideas, behaviors and ways of doing things. Often we want to do things our way—not someone else’s way. We need to experiment and make mistakes. In Stage Five we need to decide that it’s okay to learn how to do things our own way and to have our own morals and methods.1, 2, 3

Main questions to be addressed: How do I build an internal structure that supports me, as well as others? How do I develop the competence to master the technical and social skills I need to manage my own life and to live in my culture?3

Developmental Tasks of the Child:3

- To learn skills, learn from mistakes and decide to be adequate.

- To learn to listen in order to collect information and think.

- To practice thinking and doing; to reason about wants and needs.

- To check out family/caregiver rules, ideas and values, and learn about structures and people outside the immediate family or familial structure.

- To experience the consequences of breaking rules; to develop internal controls.

- To disagree with others and still be loved.

- To learn what is my responsibility and what is the responsibility of others.

- To learn when to flee, when to “flow,” and when to stand firm; to develop the capacity to cooperate.

Compromise: Failure to acquire significant skills or values will limit us as adults. For example, lack of a family structure, or clear family values, or good role models.2, 4, 5

Recycling: Returning to this stage is about updating internal structures, questioning, and relearning how to do things. We explore new values, ideas and behaviors. We may try on new social roles as we let go of old ones; making mistakes and feeling awkward or clumsy is part of this. We may seek contact with people outside our usual circle of family or friends: peer groups and same sex relationships are major themes. We are concerned with defining reality, dealing with authority, arguing and judging, and rethinking what is appropriate for our gender. Adults returning to school or other learning environments, or learning skills for a new job, may be recycling this stage.1

Clues for returning to Structure and Skills:3

- Needing to be part of a “gang” or group—or only functioning well as a loner.

- Needing to be king or queen of the hill.

- Not understanding the relevance of rules; not understanding the freedom that rules can bestow.

- Unwillingness to examine personal values or morals.

- Trusting the thinking of the group more than one’s own thinking and intuition.

- Expecting to have to do things without knowing how, finding out, or being taught how.

- Being reluctant to learn new things or be productive.

After twelve years, Stage 5 is significant1

- After updating our identity;

- When learning new skills;

- When changing cultures; and

- When caring for a six to twelve-year-old.

Affirmations for all ages:3

- You can trust your intuition to help you decide what to do.

- You can find a way of doing things that works for you.

- You can learn the rules that help you live with others.

- You can learn when and how to disagree.

- You can think for yourself and get help instead of staying in distress.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 133-134.

2 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.5

3 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 230-233. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

4 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 205.

5 Hay, J. (2003). Personal correspondence.

Stage 6—Integration and Regeneration: Twelve to Nineteen Years

Description: In this stage, we go through the cycle again—at twice the pace. The tasks of this stage focus on identity, separation, sexuality and increased competence. Preoccupation with sex and people as sexual beings is a hallmark of this stage. Adolescents may have turbulent body changes and energy levels, with higher needs for sleep. Drugs, sex and music are topics of interest; philosophical questions and social issues may become more important. Teens worry about their identity, sexuality, appearance and their future.

For example, at about age 13 (or at the onset of puberty) when they are recycling the birth to toddler stages, teens may swing from adult-style behavior to child-like phases, or explore without much concern for standards. When recycling thinking at about age 14, adolescents may sometimes intersperse reasonable and competent behavior with rebellious outbursts. During the years 15 through 17, they recycle the stage of power and identity. This typically shows up in “why” and “how come” questions as they incorporate new identities and relationships, and learn to solve complex problems. Starting at about age 16 and extending through 19, teens recycle structure. Short periods of testing or breaking rules are typical behaviors.

In Stage 6 the task is to decide that it is okay to be a sexual person, it’s okay to have a place among grownups, and it’s okay to succeed.1, 2, 3, 5

Main questions to be addressed: How can I become a separate person with my own values and still be okay? Is it okay for me to be independent, to honor my sexuality and to be responsible?3

Developmental Tasks of the Adolescent:3

- To take more steps toward independence.

- To achieve a clearer emotional separation from family.

- To emerge gradually as a separate, independent person with one’s own identity and values.

- To be competent and responsible for one’s own needs, feelings and behaviors.

- To integrate sexuality into the earlier developmental tasks.

Compromise: Failure to achieve this integration will leave us somewhat fragmented, as if somehow we have not quite finished growing up.2, 4

Recycling: As grownups revisit Stage 6 we explore many of the same themes: sex and its importance and integration into our lives, how our relationships fit with and support our adult identities and values, our personal philosophies and positions, and how we relate to the world. We may also have higher sleep needs, explore music and drugs, experiment sexually, or speak of “acting like a teenager.” We may break out of mentor relationships and enjoy the freedom of standing on our own.1, 2

Clues for returning to Integration:3

- Preoccupation with sex, body, clothes, appearance, friends or our sex role.

- Unsure of our own values; vulnerable to peer pressure.

- Problems with starting and ending jobs, roles and relationships.

- Overdependence on or alienation from family and others.

- Irresponsibility; difficulty making and keeping commitments.

- Looking to others for a definition of who we are.

- Confusion between sex and nurturing.

- Unsure of maleness, femaleness or lovableness.

After eighteen years, Stage 6 is significant1

- After developing new morals or skills;

- When preparing to leave a relationship, job, home or locality;

- When ending any process; and

- When parenting teenagers.

Affirmations for all ages:3, 5

- You can know who you are and learn and practice skills for independence.

- You can learn the difference between sex and nurturing and be responsible for your needs, feelings and behaviors.

- You can develop your own interests, relationships and causes.

- You can learn to use old skills in new ways.

- You can grow in your maleness, femaleness and/or bisexualness and still be dependent at times.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 134.

2 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.5-2.6.

3 Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 234-236. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

4 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 205-206.

5 Hay, J. (2003). Personal correspondence.

Stage 7—Recycling: Adulthood

Description: As we grow out of the teen years and enter adulthood, we have completed one full cycle of development. Our personality is framed; for the remainder of our lives we will continue to complete and refine earlier developmental tasks. Our developmental time clock doesn’t stop. Each repetition of the cycle will have its own unique qualities, rhythm and character; each will yield different “fruits.” As we recycle our perception is refined; we grow and deepen. Each beginning of the cycle is an important turning point—whether it is triggered by natural life course events, by a crisis, or simply by the age that we are. In adulthood, we may play different roles as we move through these cycles; we may also need different levels and kinds of support. We need to decide to continue getting what we need when we experience the normal symptoms of our stages, to carry out the tasks on the next level, and to learn the new lessons.1, 3

Main questions to be addressed: How will I balance my needs for competence, intimacy, connectedness and separateness with the demands of caring for others, and how will I move from independence to interdependence?2

Developmental Tasks of the Adult: 2, 3

- Any or all of the tasks for Stages 1 through 6.

- To master skills for work and recreation.

- To find mentors and to mentor.

- To grow in love and humor; to offer and accept intimacy.

- To expand creativity and honor uniqueness.

- To accept responsibility for ourselves and to care for the next generation and the last.

- To find support for our own growth and to support the growth of others.

- To expand our commitment beyond ourselves and our family to the community and the world.

- To balance dependence, independence and interdependence.

- To deepen integrity and spirituality.

- To refine the arts of greeting, leaving and grieving.

Clues to adults to redo growing-up tasks from childhood:2, 3

- Any or all of the clues relating to Stages 1 through 6.

- Overdependence; fear of dependence, or being independent to the exclusion of interdependence.

- Difficulty making and keeping commitments.

- Role inflexibility.

- Fear of growing old.

- Unwillingness to say hello and good-bye; unwillingness to grieve and then move on with life.

- Living in the past; living in the future.

- Living through others.

- Not knowing or getting what you need.

- Denial and discounting.

Affirmations for adults:2

- You can be uniquely yourself and honor the uniqueness of others.

- You can build and examine your commitments to your values and causes, your roles and your tasks.

- You can be creative, competent, productive and joyful.

- You can trust your inner wisdom.

- You can finish each part of your journey and look forward to the next.

- You can be independent and interdependent.

- You can say your hellos and good-byes to people, roles, dreams and decisions.

1 Levin, P. (1982). The cycle of development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 2, 134-136.

2 Clarke, J. I., and Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 238-240. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

3 Hay, J. (2003). Personal correspondence.

Stage 8—Toward Death: Integration of Life Experiences1

Description: During the last part of our lives, or whenever we knowingly face death, we are called to finish putting all the pieces together. Some of us don’t wait for the imminence of death to do this. We do and redo this “wrapping up,” this celebrating and grieving process, throughout our lives. This stage may be incorporated in the normal recycling process or it may be a stage that occurs only once.

If we have lived our lives through all the stages and reached this last part of adulthood—past the hustle and bustle of growing up, maybe rearing our own families and caring for the aged; past the building of our work lives and acquiring things; past the stage of devoting great effort to changing the world—then we shall reach the stage of elder and crone. Some call this the time when the old ones pass on wisdom to those who seek it.

Dying is part of living and this stage of life could properly be called “Living Until You Die.” No matter what our circumstances, this can be a time of being in charge in a new way. We can be in charge of how we see ourselves and the world. We can be in charge of what we make of every day, to the greatest degree we are able.

We sum up what we have learned from life’s experiences. We sharpen our observations and come to accept life as it is without thinking it must be changed to suit us. We prepare to relinquish certain responsibilities to those we have mentored. We understand that just about everything has a light and a dark side. There are no simple answers. We recognize the demons we may have created and devise ways to lay them to rest.

If we haven’t yet asked, What has this life been about? What was my job here? and What of that job have I accomplished? we’re likely to ask those questions now.

We take inventories. We look back and ask, “What is my unfinished business? If I died today, what would I regret not having said, not having repaired, not having done, not having been? And what will I, or what can I, do about it now?”

We are called upon to revisit not only our beliefs about life and death, but also our concepts of an afterlife. What happens after our bodies give out? This exploration usually involves becoming clear about our beliefs, about how a power within us connects with a power beyond us.

We meet each day as it comes. Development continues until we die. The tasks of this part of life call for the integration of the past with the present and preparation for the future.1, 2

Main question to be addressed: How do I complete the meaning of my life and prepare for leaving?

Developmental tasks of the older adult:

- To prepare for death; to make conscious, ethical preparation for leaving.

- To explore connections with humankind and connections with a higher power.

- To reassess artificial barriers, or judgments, that keep distance between ourselves and others.

- To adjust to and grieve the loss of any physical and mental capabilities.

- To integrate life experiences with personal beliefs and values.

- To be willing to share our wisdom; to be clear about what we have wisdom about and what we do not.

- To refine the arts of greeting, leaving and grieving.

Affirmations:

- You can grow your whole life through.

- You can make your preparations for leaving and die when you are ready.

- You can celebrate the gifts you have received and the gifts you have given.

- You can share your wisdom in your way.

1 Jean Illsley Clarke added this stage to Levin’s original developmental theory; it follows Levin’s Stage 7 (Recycling). Clarke, J. I., & Dawson, C. (1989/1998). Growing Up Again: Parenting Ourselves, Parenting Our Children. 2nd Ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden Foundation, 212, 240-242. Reprinted by permission of Hazelden Foundation.

2 Hay, J. (2003) Personal correspondence.

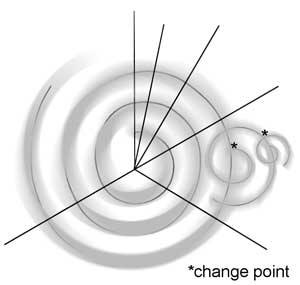

Change Points—“Spirals Within Spirals”1

Levin suggests that as important events occur, we may begin another, smaller cycle. Julie Hay has added the metaphor of “spirals within spirals” to capture this addition to Pam Levin’s original theory of developmental cycles. Hay suggests that as important events occur, whether they are positive like the birth of a baby or negative like the loss of a job, smaller and possibly even smaller spirals are spun off the major developmental stage we are in, rather like a set of Russia dolls. These “change points” or minor cycles may last a few minutes or several years. They indicate a need to go through the whole cycle in relation to the specific event.

Change points act like multipliers to whatever else we are experiencing and add layers of complexity and sometimes stress. When change points occur in stages where we are strong, we may more easily accommodate them. When they occur in stages that are challenging or difficult for us, or in stages where we may have a lot of “unfinished business,” the change points can significantly increase stress.

To illustrate, Hay uses the example of changing jobs: We have decided to accept a job at another company because we will learn new skills. Typically, when we report for work the first day, one of three things will happen: we are briefly shown around and introduced to our new colleagues; we are given work to complete immediately; or we are sent to attend a program to learn the skills we will need for the work. For most of us, none of these approaches will set up an effective transition to this new job.

There is another option. Because we can predict that changing jobs will initiate its own developmental spiral, we can use cycles of development to design a more effective transition process. Ideally, this process would incorporate all the stages in the appropriate order with some time flexibility to allow for individual differences on how quickly or slowly we accomplish the major tasks of each stage.

First, in our new job we need a time to just be—a time to get used to our new environment and put our personal possessions in our desk or workstation. We need to feel welcomed and valued by our colleagues, especially our boss. Not helpful is to feel pressured to start work immediately.

Second, we want a time for doing—a time to explore at our own pace, locate the break room, bathroom or copy room and get a general feel for the building. Also important in this stage is time to meet our new colleagues and find out what they do. It is particularly helpful if they are expecting us and we can meet them one-on-one instead of in a large group.

Now we will want time to think about our job. Getting support from our manager or boss to do this as well as an opportunity to share our views about the work is central to this third stage. A manager who allows flexibility and individuality in how to do the work, who answers questions and listens to our ideas with interest more effectively supports us in accomplishing the tasks of this stage.

Next, we are ready to create our own identity in the job. When we are able to set performance standards in concert with our manager, we have a sense of control and an element of choice over what kind of employee we will be. When this choice is denied us, we are more likely to accept the decisions of the organization grudgingly and may even become rebellious or unthinkingly compliant.

Now, we are ready to move on and learn the skills required for the work. We need to have a good idea of the job itself, and our personal identity within it, if we are going to make full use of training. With this foundation in place we can select what we need to learn, working in partnership with the trainer instead of relying on them to predict our needs. Our motivation is much higher when we know why we are learning.

Sixth, we are ready to integrate the earlier stages. As we undertake our work, we bring together the completed tasks of exploration, decision-making and learning. Gradually we begin to perform up to the standards. We continue to rework parts we missed in the earlier stages, get to know more people, and refine our identity in relation to the work. If we are prevented from making these adjustments, we will not achieve our full potential.

Seventh, we begin the recycling stage. We have completed our transition into the new job. The effect of this particular spiral will gradually fade and we will function at our peak level until another change comes along.

1 Hay, J. (1992). Transactional Analysis for Trainers. Watford, UK: Sherwood Publishing, 206-208

Using Developmental Cycles in Adult Education

When we invite groups to come together to learn, we can use cycles of development to help us plan and to give us insights into learners’ needs and responses. This article is from “Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors” by Rosemary Napper and Trudi Newton. It applies developmental cycles theory to working with adult learning groups.1

We each progress through the developmental stages on a macro or lifespan level. We also respond to more immediate events on a micro level (Hay’s change points). When forming groups it is helpful to know what stage participants are in at the macro level as well as any stages that are currently issues for them. This helps us to pay attention to the group mix and how best to interact with each participant. We can do this by asking participants questions before the group begins, either through an informal interview or a written questionnaire.

We can also assess whether any stages are particularly appropriate or inappropriate for our course or program. For example, people recycling Thinking may be attracted to programs where they learn new ideas, challenge old ones, and expand their knowledge. Adults recycling Identity may be more motivated by personal growth courses, while those recycling Skills may want “hands-on” or vocational-type programs.

Effective program design pays attention to and incorporates all the stages.

These questions can guide us in our program design using cycles of development:

- How do we welcome adult students or learners into our programs or courses?

- What “ice-breakers” can we use to allow people to do something successfully?

- What can we give participants to think about early in the program in a way that involves them and gives them permission to ask questions and give opinions?

- What opportunity can we give new participants to consider their identity in relation to what they are learning?

- Acquiring new skills involves practice—how do we build this into our program design?

- How do we encourage learners to apply their learning wisely?

- How can participants be enabled to adapt the learning to their own style?

| Stages | Teaching/Learning Activity |

|---|---|

| Being | Warm up |

| Doing | Focuser—reflective activity—sharing experience/ brainstorming |

| Thinking | Input/theory/concepts/models/demonstration/rationale/ how to . . . |

| Identity | Applying thinking to one’s own work and life experiences |

| Skills/Structure | Practice |

| Integration | Consolidating learning through projects, applications and summaries |

Supporting Adult Learners to Learn

If we have used developmental cycles as a way to structure a program, as teachers or facilitators we also need to know when and how to intervene if learners get “stuck” in a particular stage (learning activity). For learners to move on to the next developmental stage or learning activity, they need a sense of completion of the developmental task in their current stage. There are two types of interventions a teacher or facilitator can make to support completion and facilitate movement:

- The previous developmental stage is likely to be an area of strength for the learner and feel comfortable: reinforce this strength.

- To help a learner move from a stage where they are stuck, use affirmations (see chart) to affirm the individual’s development in that stage.

Group Development

Consider how a program comes into Being. The early stages are about Exploring or Doing—how we relate to each other (as teachers and participants), and what the environment and the program are like. As people begin to feel more secure they begin Thinking about the learning task, exchanging opinions with each other, and perhaps criticizing and challenging the group leader. As participants and leaders get to know each other and the program more, individual and small group Identities emerge; the leader may be less inhibited about playing into participants’ expectations or the leader’s expectations of themselves. As the group settles more into the learning task and begins to accomplish their own learning it becomes more Skillful—as does the leader—in managing the dynamic of the group and the curriculum.

This commitment may seem to occasionally disrupt or regress during the Integration phase, well into the course. For example, the most unlikely people are suddenly absent or are heard to make rebellious remarks; the class clown produces an excellent piece of work; the challenging subgroup at the back scatters, members sit elsewhere and are warm and friendly; a happy-looking participant arrives distraught.

Any long break between meetings may cause a change in the group’s development. At the next meeting, they may appear to rapidly Recycle—needing to come together and be as at the beginning, sharing events that have happened in the interim period, thinking ahead to what’s next, worrying about what they remember, and gradually settling down to develop skills.

Creating Teams, Sub-Groups, and Pairs

One consideration arising from Cycles of Development might be how to invite harmonious pairs or subgroups. It is likely that left to their own devices, people will gravitate to people like themselves.

Generally a mixture of individuals in a variety of different stages of development or recycling will provide the most effective group, in the sense of being able to range widely and with some depth. However, careful construction of the tasks and the role of leaders will help to minimize conflict over differences. Therefore it is important to value all members of the group overtly, highlighting the strengths of each. For example, those who are

- harmonizing, carrying out the task;

- acting, risk taking, getting on with it;

- thinking, analyzing;

- shaping, providing direction;

- practically skilled; and

- pulling it all together, finishing off.

1 Napper, R., & Newton, T. (2000). Tactics: Transactional Analysis Concepts for All Trainers, Teachers and Tutors. Ipswich, UK: TA Resources, 2.7-2.12.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2003

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Sarah E. Harebo, Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).