Bulletin #3106, Using Refugee Voices to Improve Cross-Cultural Conversations: Research with New Mainers

By Jane Haskell, Extension Professor, University of Maine Cooperative Extension and Ashley Storrow,

Assistant Program Manager, Language Partners & Refugee and Immigration Services, Catholic Charities Maine

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents

- Purpose

- Background and Resettlement

- Project Design

- Focus Groups: Invitation and Participation

- Results: A Snapshot

- Recommendations

- Is This Just Ink on Paper?

- Conclusion

Since 1990 Maine, like most areas of the United States, has seen an increase in primary and secondary refugees locating in our communities. According to Welcoming America, this decade’s number of immigrants to the U.S. is unmatched since the early 1900’s. Catholic Charities Maine reports that every year more than 250 primary refugees, 200 asylum seekers, and other immigrant groups arrive in Maine from war torn counties. Immigrants arrive with aspirations to be self sufficient and active members of the community; however, many factors including cultural differences contribute to a climate that is ripe for misunderstanding. This white paper presents findings from a 2013-2014 research project exploring how to strengthen a community’s capacity for cross-cultural conversations with newly-arrived refugees in Portland, Maine.

Purpose

UMaine Extension was asked to help evaluate a pilot refugee-mentoring program developed by Catholic Charities Maine (CCMaine) Refugee and Immigration Services (RIS) in August 2013. During the assessment, evaluators (this paper’s authors) noted differences between how mentors provided “feedback” about the mentoring program and how refugee mentees provided “feedback.” To better understand Maine’s newly-arrived refugees’ perceptions of “program feedback,” a Participatory Development research project was designed to uncover the implications embedded in organizational cross-cultural conversations.

Background and Resettlement

Annually, Maine accounts for less than half of one percent of the U.S.’s 70,000 incoming refugees (U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, 2014). Every year approximately 200-350 primary refugees and 50 or so secondary refugees[1] enter Maine, a state that, according to a 2012 U.S. Census estimate, is 95% white English speakers with only 3% of the population foreign born. Primary refugees arrive in Maine directly from a country of asylum and are considered “newly arrived” for up to one year after their arrival in Maine. A secondary migrant is a person who entered the United States as a refugee, was settled in one state, and then chose to relocate to another state. Recently, increasing numbers of New Mainers are arriving from Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Sudan. Refugees in Maine and across the nation are often locating in towns and cities without a recent history of refugee immigration.

When refugees enter the U.S. they embark on a 90 day resettlement process that assists refugees in becoming self-sufficient community members. Resettlement is a partnership between the refugee, the community, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and the voluntary resettlement agencies.

Project Design

UMaine IRB approved the research, Refugee Perspectives: Using Refugees’ Voices to Improve Programs, that utilized Participatory Development methods to understand (1) what the refugees’ histories with feedback were in their countries of origin and are now in the U.S., (2) how they would like to be asked their opinions, and (3) their recommendations for future improvements in the resettlement program with an eye toward strengthening a community’s capacity for cross-cultural conversations.

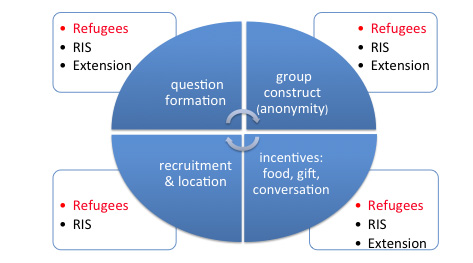

The study used focus groups to collect data; the investigators collaborated with refugees regarding focus group construct, question formation, recruitment, and participation benefits. Collaboration with refugees before the focus groups heightened investigator awareness that routine meeting methodologies and processes, to include feedback, were rooted in western concepts and constructs. The research became a microcosm of a larger question of how we, native English speakers and American-born citizens, could provide an environment for New Mainers to feel comfortable in sharing their opinions and ideas and, concurrently, provide a platform for us to receive relevant information as we provide programs for New Mainers.

Using a process similar to “regular” focus groups, the refugee project advisors and participants helped us understand refugees’ reticence when sharing opinions or ideas, i.e., providing feedback. Refugees shared experiences from their countries of origin where sometimes severe punishment was the consequence of open and honest sharing of ideas. This frame of reference helped us understand the differences between U.S. concepts of safety, anonymity, confidentiality, and right versus wrong answers.

Focus Groups: Invitation and Participation

Newly arrived refugees were invited to participate in the research study because we acknowledged that they are the experts on what it is like to be a refugee. In addition to asking for ideas to shape future refugee programs, we also wanted to understand how refugees think Maine organizations and institutions can use their opinions.

Participants were required to have been in the United States for at least 90 days and to have completed resettlement, to be able to reflect on that experience. They were recruited by RIS using flyers translated by refugees to Arabic and Somali and by refugee-to-refugee word of mouth.

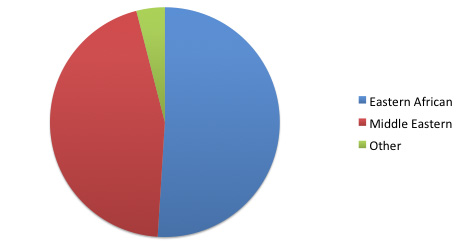

Four focus groups were held between December 2013 and April 2014. Thirty-four people participated from six different countries: three East African1 and three Middle Eastern2. Twenty-one of the 34 were from Iraq. Three-quarters of participants had been in Maine a year or less; 62% had been here for less than six months.

New Mainers’ focus group questions.

- What were your needs or requirement when you first arrived in Maine?

- How would you describe the word feedback?

- In your country, what was your experience in sharing your opinions and ideas? What was feedback used for?

- How can organizations help refugees feel safe to share their opinions about what they need with that organization?

- Why would refugees not feel comfortable giving feedback or sharing their ideas or opinions?

- What are good ways to get opinions from the refugee population about an organization? A program?

- If you could predict a future refugee program, what would it be like? How would you know it was working?

Each 90-minute focus group, with four to 16 participants, responded to seven questions. To assure anonymity, only first names were used. Rather than audio- or videotaping, responses were written in English on flip charts for all to see. Permission was received for one investigator to simultaneously record responses on a laptop. Arabic, Somali, and Persian interpreters were used. To model Participatory Development and promote safety, each session was hosted at CCMaine to provide a familiar location.

Research consent forms, available in Arabic, Somali, and English, did not need to be signed. Session guidelines stressed confidentiality, that different opinions were okay, and that there were no right or wrong answers.

Results: A Snapshot

There was no common understanding of the word “feedback” among the participants. Sharing opinions and comments was not allowed, “did not exist” or was punishable (except if it was positive) in their countries of origin. New Mainers are seeking security, hoping to reverse this deep-seated lack of trust that they had experienced. When asked, “How can organizations in the U.S. help refugees feel safe to share their ideas and opinions about the organization?” they replied, “Welcome us.” “Trust us; we want to trust you.” “We need to be secure.” “We need a safe place to live and have education for our children and learn how to speak English so we can work. We need to be in relationship with you.”

A common perception shared by newly arrived refugees is that being ignored, not listened to, or being told what to do and how to do it is being perpetuated in this country. “People ask (about my needs or experiences), but don’t listen.” This experience, reminiscent of their pasts, then leads to a fear and a lack of trust, especially when people feel that speaking their truth will compromise their security. One participant gave the example that if one of their requirements is a safe haven, a place to live, and they are moved to substandard housing and speak of bedbugs or other pests, and are ignored or told that it is all there is for them, they may feel they will be deported if they complain further.

No audio or video record of the focus groups exists to illustrate the climate in the room. The researchers observed typical group dynamics where the sessions were reserved at the beginning with more lively conversation as the questions deepened. One difference was that the lively, full-group, multi-minute discussions were in Arabic. These animated, non-English conversations, when summarized by interpreters and other participants, were focused on basic human rights and their futures.

Recommendations

In conclusion, we hope these findings, supported by other scholarly work, serve as a catalyst for strengthened cross-cultural conversations. Here are some simple practices that will begin to “make a difference” and engage New Americans in ways that are refugee-community-friendly:

- Ensure refugees understand their rights and responsibilities at the beginning of an organization’s program. This leads to a feeling of safety.

- Provide opportunities for one-on-one relationships and outreach: i.e. mentorship, volunteer programs, counselors, tutors, etc. This leads to a feeling of safety and welcome.

- Explain “confidentiality” as it relates to that program. This leads to a feeling of safety and trust, and an understanding of rights.

- When gathering participant recommendations, use focus groups, storytelling, or outreach conversation not surveys or scalar types of evaluation; really listen — it is seen as respectful.

- Ensure, and assure, that respectfully sharing opinions and ideas will not lead to cuts in services or other similar negative consequences.

- Use interpreters to ensure people are able to fully express themselves and do not feel silenced.

Is This Just Ink on Paper?

Newly arrived refugees were asked to trust and share their opinions and ideas with researchers about a system that can intimately affect their immediate and long-term futures and that of future refugees. This research brought to light the debated question in Participatory Development — Can quality of life be improved when one entity (institutions/agencies) has greater power than the other (refugees)?

The people in each focus group voiced the question of whether this research will impact their future and said it more simply and with compelling passion, “Will this make any difference … or is it just ink on paper?”

Many Americans may forget that freedom of speech is a basic human right and take for granted the ability to share our opinions. Many refugees, by definition, have not had those same experiences.

Conclusion

This project demonstrated that refugees see ‘feedback’ as a basic human right regarding freedom of expression. Many refugees stated they left their homes because they were silenced. By believing and trusting that refugees are the experts on their condition and needs, organizations can improve their effectiveness.

The authors were humbled by the frank expression of experiences, opinions, and ideas shared and often animatedly discussed by newly-arrived refugees during this study. Four official and many unofficial interpreters helped us hear these 34 New Mainers’ voices.

Reviewed by:

Catherine Elliott, Extension Specialist, UMaine Extension

Bethany Sack, Volunteer Programs Coordinator, Refugee & Immigration Services, Catholic Charities Maine

Judith Southworth, Elder Refugee Services, Catholic Charities Maine

1 Sudan, Somalia, and Djibouti

2 Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2014

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Sarah E. Harebo, Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).