Maine Home Garden News — May, 2010

- May is the month to . . .

- Deer in My Garden!

- How to Rejuvenate Your Old, Overgrown Lilac

- Earlier and Increased Yields by Using Plastic Mulches and Row Covers

May is the month to . . .

By Dr. Lois Berg Stack, Extension Specialist, Ornamental Horticulture

- Check temperatures to determine planting dates. Use a soil thermometer to track the temperature of the soil in your vegetable garden. Insert the thermometer probe to the depth you will sow seeds (1-2″). Test the temperature in the morning. When the soil temperature reaches 45°F for at least three consecutive days, you can confidently direct-seed these vegetables: broccoli, spinach, peas, lettuce, carrots, beets, onions. When soil temperature reaches 50°F, you can direct-seed these vegetables: radish, cabbage, cauliflower, Swiss chard. When the soil temperature reaches 60°F, you can direct-seed these crops: beans, corn. When the soil temperature reaches 70°F, you can direct-seed these crops: cucumber, pumpkin, squash, pumpkins, melons.

Harden off seedlings before planting. If you’ve grown your own seedlings indoors, it is important to acclimate, or harden, them. You can do this in any of these ways: (1) Set seedlings outside during the day and bring them indoors each night. (2) Put seedlings into a coldframe. (3) If you have a high tunnel or hoops covered with plastic, put the seedlings inside them. Whichever method you use, acclimate your young plants for 10-14 days before planting them into your garden. During this time, check the plants daily, and water and fertilize them normally. If you purchase your seedlings, ask if they’ve been hardened off.

Harden off seedlings before planting. If you’ve grown your own seedlings indoors, it is important to acclimate, or harden, them. You can do this in any of these ways: (1) Set seedlings outside during the day and bring them indoors each night. (2) Put seedlings into a coldframe. (3) If you have a high tunnel or hoops covered with plastic, put the seedlings inside them. Whichever method you use, acclimate your young plants for 10-14 days before planting them into your garden. During this time, check the plants daily, and water and fertilize them normally. If you purchase your seedlings, ask if they’ve been hardened off.- Make sure all your tools are functional. Sharpen pruning shears, loppers, and saws. Inflate the tires of your garden carts and wheelbarrows. Sharpen lawn mower blades. Repair leaks in hoses, replace hardened or missing washers, and replace leaky spray nozzles.

- Inspect before buying! Inspect straw and other mulch materials before purchasing them, to be sure they do not contain excessive weed seeds and are not moldy. Do the same for loam and topsoil. Check the root balls of trees and shrubs, to make sure they do not contain weeds that you could transplant into your garden, or European fire ants that could become established in your landscape.

- Plant some cut flowers. Even if you haven’t grown cut flower seedlings, you can grow cut flowers for very little money. Try gladioli; plant several corms every ten days from late May through late June for a continual supply of cut flowers from midsummer through early fall. Direct-seed zinnias, perhaps the most productive cut flowers, in late May or early June. Direct-seed calendulas now; they can be used as colorful cut flowers or as additions to salads and herbal vinegars.

- Keep records of plant performance. Start with your spring bulbs. Even daffodils decline after several years, and need to be dug up, divided, and replanted. Assess your bulbs as they flower this spring. Mark with a stake in the garden, or make a note on your garden map, any bulb plantings that need to be divided this fall.

- Prune spring-flowering shrubs after their flowers fade. Forsythia, rhododendron, fothergilla, lilac, and flowering almond are among the shrubs that flower in spring. After you’ve enjoyed their display, prune them for form (check Bulletin #2169, “Pruning Woody Landscape Plants” for information about timing, techniques, and tools). They’ll have the rest of the summer to produce vigorous new growth, plus flower buds for next spring.

- Fertilize your lawn, but only if needed. If your soil test results recommend fertilizing, early May is a good time to do it. Apply not more than one pound of fertilizer per 1000 square feet of lawn. When shopping, look for a lawn fertilizer with at least 50% of its nitrogen in slow-release form, and with little or no phosphorus. Most home lawns in Maine do not need supplemental phosphorus, which can run off into lakes and streams where it causes serious problems. And remember … all summer long you can fertilize your lawn by using a mulching mower that returns the clippings to the lawn, allowing you to reduce the fertilizer you need to buy by one-third.

- Manage your vegetables for high yield. Thin carrots to one-inch spacing, so that they have room to mature. Also thin lettuce, spinach and beets. Harvest radishes before the heat of summer. Mulch new vegetable plantings with straw to conserve water and reduce weed growth.

- Use the “Early Detection/Rapid Response” method to manage invasive plants. Learn to identify invasive plants as young seedlings, and remove them promptly. Multiflora rose, shrub honeysuckle, and sweet autumn olive plants are easy to pull out when they’re young seedlings. If you wait until they’re large plants, the process is more time-consuming and causes more disruption to your plantings.

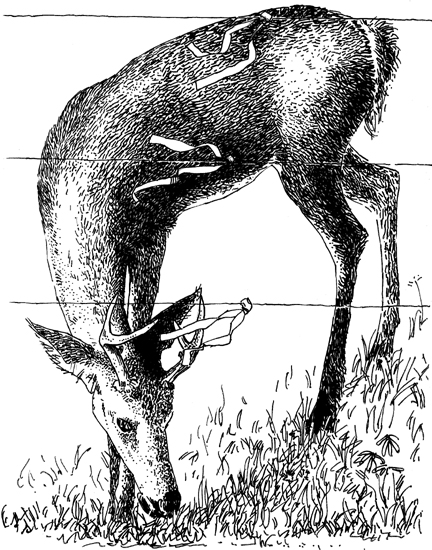

Deer in My Garden!

By Donna Coffin, Extension Educator, UMaine Extension, Piscatiquis County, donna.coffin@maine.edu

A few weeks ago, you spent some time tilling your garden spot and planted a large crop of peas and beans. Last year you remember that just before they started to blossom, deer came into your garden and ate all your nice succulent, tender young peas and bean plants leaving you empty handed. What can you do to prevent this from happening this year as you look out through the kitchen window at a herd of five deer waiting at the garden’s edge for the plants to get big enough for them to eat?

Fences

Although building a fence isn’t always feasible, fences are the best deer deterrent. Many kinds of fences have been designed to exclude deer and each has advantages and disadvantages. Factors to consider include cost, appearance, the size of the area to be enclosed, and the degree of control required. Few are 100 percent effective.

For a small garden patch, a four-foot high fence, or snow fence will work because deer avoid small, fenced-in areas. For a larger lawn or garden, a fence made of wire angled away from the yard creates both a psychological and physical barrier. Deer hesitate to jump over something in which they fear they may become entangled. The fence should be six feet high and have a 30 degree angle to be effective. Also, wire mesh fence with 6″ x 6″ openings (used in cement floors) laid on the ground around a garden can deter deer, again for fear of getting their feet entangled in the wire.

Electric fencing with a low impedance charger is used frequently by vegetable, small fruit, and tree fruit growers. Strips of aluminum foil smeared with peanut butter affixed to electric fencing lure deer to the fence where they lick the peanut butter and get a shock. Electric fences attached to a higher voltage charger can deter deer because they can hear the hum of the charge through the wires without touching them. However, electric fences may not be suitable for all areas, especially when children are present.

For more information about electric fences and how to build them, see the Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management (Cornell University, Clemson University, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and Utah State University).

Repellents

Some people claim to get good results with repellents. But there are many kinds of repellents and results seem to vary from place to place and from year to year. Contact repellents are applied to the plants, causing them to taste bad. Some repellents are simply placed in the problem area where their foul odor has a repellent effect. Six repellents were tested in a recent Connecticut study. Generally, repellents were more effective on less preferred plants. Here are the findings:

- Big Game Repellent, also known as Deer Away, made from putrescent (rotten) whole egg solids was 46 percent effective.

- Hinder, made from ammonium soaps of higher fatty acids, was 43 percent effective.

- Thiram, a bitter tasting fungicide, now commonly used in repellents, was 43 percent effective.

- Mesh bags of human hair, collected from hair styling shops, was found to be 34 percent effective. (Hair should be dirty, not collected after a shampoo.)

- Magic Circle deer repellent, a bone tar oil which was soaked into 10 by 30 cm. burlap pieces, was 18 percent effective.

- Miller Hot Sauce, containing capsicum, an extract of hot peppers, was 15 percent effective.

- Repellex is another recently introduced deer repellent for ornamental plants. It comes in two forms. One is a liquid which is sprayed on the foliage. The other is a dry product with a fertilizer analysis of 14-2-2. This form is a systemic repellent. It is worked into the soil surface and then watered in. The plants absorb the repellent, and one treatment is said to be effective for up to two years.

Some people believe that blood meal deters deer. Others claim to get results by tying pieces of deodorant soap on the branches of trees. A large bar is cut into about six pieces and each piece is placed in a mesh bag. Heavily perfumed soap is preferred. Non-deodorant soap does not seem to work as well. Predator urine and manure are sometimes used to deter deer.

Here is a home made repellent to try: Blend two eggs and a cup or two of cold water at high speed. Add this mixture to a gallon of water and let it stand for 24 hours. Then spray the mixture on foliage. The egg mixture does not wash off the foliage easily, but re-application two or three times a season may be needed. (For a larger quantity, blend a dozen eggs into 5 gallons of water.) This mix is also said to repel rabbits.

Scare tactics

The effectiveness of light and noise scare tactics are usually temporary, but some people vouch for the “scarecrow” brand sprinkler which uses a motion detector to blast intruders (anything moving) with water. It costs $80-$100, depending on the source.

Hunting

Hunting is the primary means of controlling Maine’s deer population as a whole. If you are not a deer hunter yourself and you live in a rural area, let the local game warden know you are having problems with deer and they can direct hunters to your area during deer season to help reduce the population of deer.

Deer resistant plants

People often ask for lists of plants that deer will not eat. There are many such lists, but they are not entirely reliable because deer eat almost any plants when they are hungry enough. See Landscape Plants Rated by Deer Resistance (Rutgers) for a list of “deer resistant” plants.

References

Beth Jarvis, B. & D. Bavero, Coping With Deer In Home Landscapes, Yard & Garden Brief, University of Minnesota Extension Service, 2000, http://www.extension.umn.edu/projects/yardandgarden/ygbriefs/h462deer-coping.html

Craven, S. & S. Hygnstrom, Deer, Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management, http://icwdm.org/handbook/mammals/Deer.asp

Drake, D., P. Nitzsche, & P. Perdomo, Landscape Plants Rated by Deer Resistance, E271, Rutgers NJAES Cooperative Extension, 4/25/2003. http://njaes.rutgers.edu/deerresistance/

How to Rejuvenate Your Old, Overgrown Lilac

By Marjorie Peronto, Extension Educator, Hancock County, marjorie.peronto@maine.edu

Are you getting ready to prune an old fashioned lilac that has become completely overgrown? I’m talking about that dense shrub with stems as thick as small trees interspersed with suckers of all sizes; the shrub that is now reaching 15′ to 20′ tall, with all of its blossoms swaying way above your head. How do you rein it in?

The first thing to think about is timing. If you are like me, you do most of your pruning work in the late winter/early spring, when trees and shrubs are dormant and bare naked, so you can really see what you are doing. BUT, the flower buds that are on your lilac right now were formed last summer. They made it through the winter and are now ready to burst forth. If you had pruned your lilac during this past dormant season, you would have removed part of this spring’s floral display. For that reason, many people wait until just after their lilac has finished flowering, then break out the pruning tools. Once the flowers have faded, lilacs will start setting next year’s flower buds almost immediately, so don’t wait too long or you’ll sacrifice next year’s flowers.

If your plant is seriously overgrown, it may take you a few years to bring it back to a manageable size. Start by removing any dead, damaged or diseased wood that you see (“the three Ds”). Once you’ve cleaned these out, look for the thickest, oldest stems, and remove them at ground level. Do not take out more than 1/3 of the shrub’s stems in any given year. This approach will accomplish a few things. It will make a noticeable reduction in the shrub’s height, as the oldest stems also tend to be the tallest. It will open the plant up, allowing for better air circulation and sunlight penetration. And it will stimulate the growth of vigorous new shoots which will bear flowers within sniffing range in future years. Most lilac flowers are produced on the top or terminal pair of buds. As branches age and get taller, flowers are produced farther and farther away from our noses.

Once you’ve removed the three Ds and some of the oldest stems, fine tune your pruning by removing the pencil-thin suckers and twiggy growth coming up from the base of the plant. Leave the vigorous, healthy looking young shoots. Within a couple of years, these should be flowering. When pruning, keep an eye out for crossing, rubbing branches as well, as these will eventually result in wounds in the bark as they grow in diameter. Wounds are openings for disease organisms to enter the plant.

Plan to prune your lilac once a year to keep it thriving, removing no more than one third of the oldest, thickest stems. Strive for a plant with 8 to 12 stems of various ages, all between 1″ and 2″ in diameter.

Earlier and Increased Yields by Using Plastic Mulches and Row Covers

By Mark Hutton, Extension Educator, Highmoor Farm, mark.hutton@maine.edu

Plastic mulch alone or in combination with row covers can be of great benefit in the home vegetable garden increasing earliness, yield, and quality. The benefits to using plastic mulch in the garden include

- soil warming

- decreased weed competition

- moisture management

- reduced nutrient leaching

- disease reduction

- decreased soil compaction

Row covers also increase early yield and provide frost protection and act as a barrier to insect attack.

Perhaps the most important benefit of plastic mulch is the increase in soil temperatures. Black plastic mulch can produce soil temperatures up to 5°F warmer at a depth of 2 inches compared to bare soil. In order to achieve maximum soil warming the plastic mulch should be in good contact with the soil surface and stretched tightly. Black plastic mulch warms the soil by physically conducting the heat into the soil. The soil remains warm because the mulch prevents radiant cooling trapping the heat in the soil. Clear plastic mulch increases soil temperature to an even greater extent (7-14°F over bare soil) than black plastic mulch by allowing solar energy to directly warm the soil. Clear mulches have the disadvantage in that sufficient light passes thorough the plastic to allow for weed growth. Infrared transmitting mulches (referred to as IRT mulch) are green in color and are a compromise between black and clear plastic – warmer than black (6-10°F over bare soil) but not weedy like clear mulch.

Plastic mulches are put in place in the early part of the growing season when there is plenty of soil moisture. In most soils, the combination of adequate soil moisture when the plastic is put in place and lateral movement of moisture in the soil is sufficient for most crop needs. Supplemental irrigation can be provided by water in the plants through the planting hole or by installing trickle irrigation tubes under the plastic. Plastic mulch creates a physical barrier to weed growth. Organic mulches can serve this purpose. However, organic mulches such as straw or grass clippings can actually reduce soil temperatures and delay harvest. Covering the soil in the garden with mulch reduces the amount of nutrient leaching from rainfall. Fertilizer applications can be reduced through banded fertilizer application under the mulch putting the fertilizer right where the plant needs it rather than broadcasting over the entire garden. Plastic mulches help reduce diseases in two ways. First, covering the soil surface around the crop can prevent disease organisms from splashing up from the soil onto the lower portions of the plant during rainfall. Additionally, mulches are a barrier between fruit and the soil which reduces fruit rots in crops like cucumber and melons.

Row covers can be used in combination with plastic mulch to further increase earliness and yield. Row covers are used in two ways: as “floating covers” loosely applied right over the crop or held up off the crop in mini-tunnels. Floating row covers are woven or spun bonded polypropylene or polyester fabric. Row covers come in different weights (thickness) and sizes. The heavier covers can provide significant frost protection (down to 28°F) and are especially useful to extend the harvest of cool season crops late into the fall. Lighter covers are used in the spring and summer to increase temperatures around the plant and also as physical barriers protecting crops from several types of insect pests. Leafy crops like salad greens, spinach, cabbage, and broccoli benefit from the use of row covers in the early season and in the fall. Warm season fruited crops like cucumbers, squash, and melons show great response to the use of row covers and mulches. However, the covers must be removed at flowering to allow for pollination of the crop. Mini-tunnels are created using heavy (9 gauge) wire hoops arched over the crop and then covers with silted clear plastic or fabric row cover. Mini-tunnels will work for all the garden crops. If you choose to use row covers with tomato, pepper, or eggplant mini-tunnels are essential. These crops grow fine under “floating” row covers, but yields will be delayed or reduced due to the abrasion of the “floating” cover rubbing on the plant, damaging the flowers. Row covers are a valuable addition to your garden “tool” box and with careful handling and storage can be used over several seasons.

Row covers can be used in combination with plastic mulch to further increase earliness and yield. Row covers are used in two ways: as “floating covers” loosely applied right over the crop or held up off the crop in mini-tunnels. Floating row covers are woven or spun bonded polypropylene or polyester fabric. Row covers come in different weights (thickness) and sizes. The heavier covers can provide significant frost protection (down to 28°F) and are especially useful to extend the harvest of cool season crops late into the fall. Lighter covers are used in the spring and summer to increase temperatures around the plant and also as physical barriers protecting crops from several types of insect pests. Leafy crops like salad greens, spinach, cabbage, and broccoli benefit from the use of row covers in the early season and in the fall. Warm season fruited crops like cucumbers, squash, and melons show great response to the use of row covers and mulches. However, the covers must be removed at flowering to allow for pollination of the crop. Mini-tunnels are created using heavy (9 gauge) wire hoops arched over the crop and then covers with silted clear plastic or fabric row cover. Mini-tunnels will work for all the garden crops. If you choose to use row covers with tomato, pepper, or eggplant mini-tunnels are essential. These crops grow fine under “floating” row covers, but yields will be delayed or reduced due to the abrasion of the “floating” cover rubbing on the plant, damaging the flowers. Row covers are a valuable addition to your garden “tool” box and with careful handling and storage can be used over several seasons.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications fill out our online form.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around the state, with Professor Richard Brzozowski serving as editor.