Allagash, “Tom Gardner’s Stories”

Story: “Tom Gardner’s Stories”

Storyteller: Jim Connors

Town: Allagash, ME

ID: NA 2891 CD 491 Track 2

Collector: Helen K. Atchison

Date: 1972

Motif: The buckwheat story fits X1122.1 (Lie: hunter shoots projectile great distance) and is similar to X1122.3 (Lie: ingenious person bends gun barrel to make spectacular shot); The story of canoeing through the rapids best fits W117 (Boastfulness) and/or somewhere in F660 (Remarkable skill).

The story heard here actually consists of two short stories, both told by Tom Gardner (often called “Old Tom” to distinguish him from his son), a famous Maine Guide from Allagash. Gardner was supposedly born on a boat while his parents were wintering on their way up the St. John River. According to a history of Aroostook County, Pine, Potatoes, and People, he was one hundred years old when he last steered a tow boat up the Allagash River, toting supplies to the logging camps. He was one of the early professional guides who took sportsmen and women all over the northern Maine woods, rivers, and lakes in search of fish, deer, and various other game and fowl.

Before addressing the stories heard here individually, a brief history of the Maine Guides provides some background for the tales. The professional Maine Guide evolved for 300 years before maturing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The guide’s forerunners were the Eastern Abenaki Indians who greeted Maine’s first European explorers. They guided military officials, priests, traders, and lumbermen throughout the forests and instructed them in local lore along the way. In some instances the Native guides were paid, but they did not operate regularly or as a professional service. As more explorers, traders, and eventually settlers moved in, the amount of unexplored territory dwindled and Europeans came to know region well. By the late-1800s, the wilderness was being mapped for the lumber industry and the men involved in every part of the process were becoming more familiar with various areas across northern Maine. This industry produced a large pool of men familiar with rigorous living, the harsh environment of the forest, and (along with farmers) seasonal jobs. It was some of these men who became the earliest Maine Guides, though it was still considered “off season” work, not their main occupation.

Conditions for a “guiding industry” became near perfect by turn of twentieth century as southern New England (and other parts of the country) were largely industrialized and had little remaining wilderness areas. Industrialization produced a wealthy class of sportsmen who desired the tranquility and trophies of northern Maine. Mainers were able to capitalize on this market by filling two remaining needs: transportation to wild areas (filled by expansion of various railroads through Maine and Maritimes) and people with foresight and planning capabilities to build the foundation of a guiding industry (accomplished by many individuals throughout the state). Guides were responsible for nearly everything, including knowledge of where to find the desired fish and game, food preparation and setting up camp, and even providing entertainment as needed along the way and especially after dinner. Guiding has changed since the days of Old Tom, but good guides continue many of the old traditions. A day with a Maine Guide is more than just a fishing or hunting trip.

The first story tells how Tom’s father sold buckwheat. In the story, Tom mentioned that his father was selling “on the island.” He was most likely referring to folks living on one of the islands in the St. John River, which means his father was probably living on shore. The story fits the long history of stories of the remarkable gunman (or woman) and his or her remarkable gun. These stories usually, at least those told in the Northeast, more commonly referred to hunting, thus this story is somewhat unusual. The distance from the shore to the island in this case was not a great distance to shoot, but distributing buckwheat for sale this way would be incredible (and spreading it as described would be impossible). Buckwheat used to be an important crop in the Northeast, and particularly among the Acadians in northern Maine and New Brunswick where it is still featured in traditional dishes such as ployes, a buckwheat pancake.

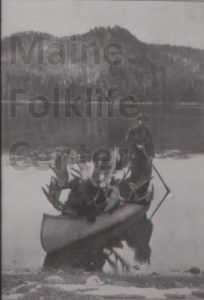

The second story included here deals with the skills of a good canoe-man. The canoe usually used by Allagash guides – it is worth noting that guides in different areas preferred different types of boats – was a twenty foot, double ended, canvas covered, cedar ribbed canoe. These early canoes were wider than modern versions and this design was preferred because it drew less water, was more maneuverable, and carried a load better through rough water. On a lake, the guide would paddle; on a river, the guide used a “setting pole,” an eighteen foot, green hardwood pole with a blunt metal tip. With the pole, the guide would either push the canoe upriver or slow the canoe’s descent through rapids. Poling was a difficult practice, but an experienced guide could use eddies created by large rocks or a bend in the river to build speed and pass through rough spots untouched. If traveling downstream, a guide would extend the pole out in front and steer with ease. For guides, the pole was preferred over the paddle for slowing or even stopping the canoe to position it for a tight passage or allow a sport to toss a fly into a desired spot. Travel by canoe was particularly important for both people and supplies in Spring as roads were often not passable, or at least much slower going than rivers swollen by melting snow. As demonstrated in the story, skill in a canoe was highly valued and subject to bragging rights. Twin Brook Rapids, the sight of the action in this story, is located on the Allagash River not far south of town of Allagash.

Transcript:

Tom Gardner, as I said, was a guide and an excellent canoe-man. And, in those days, when you had a party and you were guiding them up the river, after you had the evening meal you also were supposed to have the capacity to furnish some entertainment for your party. Tom Gardner was a past master at telling stories. He’d tell the story of his father selling buckwheat on the island in the Spring when he couldn’t get to the island. He’d have the ground all prepared from the Fall before, and in the Spring when it was time to sell the buckwheat he just went out on the bank with his double-barreled shotgun and his buckwheat, and he loaded both barrels and shot the buckwheat across on the island. Someone asked him how he got the buckwheat to spread, and Tom said, ‘That was no problem, he just waved the barrel when he was pulling the trigger.’

Then, he was telling one evening, at [?] Depot, that was a stopping point when we had a party going up the river, he was telling the party about how fast he went up through Twin Brook Rapid one time using the end over end method. And he said, ‘Well, I’ll just tell ya, I went up through there fast enough that I pulled that pole up out of the water and there was a row of holes where that pole came up that drifted right back down through the rapids behind that canoe.’ Fred Hafford was along, one of the guides; Fred laughed a little bit. Tom said, ‘I don’t suppose you believe that, do you, Fred?’ Fred said, ‘The Hell I don’t, Tom, I came up the river just a little bit behind you using the same holes!’

Sources: Hamlin, Helen. Pine, Potatoes, and People: The Story of Aroostook. New York: W. W. Norton, 1948, 124-27; & Lowery, Nathan S. “Tales of the Northern Maine Woods: The History and Traditions of the Maine Guide,” in Northeast Folklore 28 (1989), 69-110.